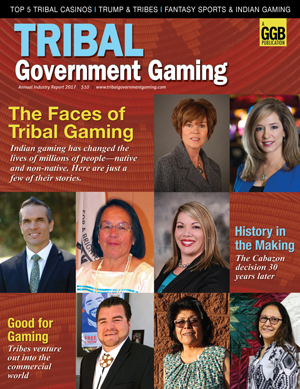

The success of the Indian gaming industry hinges on the dedication of the people who operate, regulate and advise the Indian casinos. Here are profiles of 10 of the very best professionals who make tribal government gaming happen.

Planning for the Future

Delia M. Carlyle, Tribal Council, Ak-Chin Indian Community

Thirty-two years of on-and-off serving in tribal government with the Ak-Chin Indian Community in Arizona has given Delia Carlyle an unorthodox perspective on tribal gaming.

Thirty-two years of on-and-off serving in tribal government with the Ak-Chin Indian Community in Arizona has given Delia Carlyle an unorthodox perspective on tribal gaming.

“I don’t like to say that we’re a ‘gaming tribe,’” she explains. “We’re a farming tribe that happens to have a casino.” Carlyle emphasizes that the foundation of the Ak-Chin community has always been agriculture, and that gaming is a means of building upon that.

The community sits near the fast-growing city of Maricopa, just south of the Gila River Indian Reservation, and roughly 35 miles south of the Phoenix metro area. The tribe grows pecan nuts, cotton, alfalfa, corn, potatoes and other crops.

While other tribes have become overly dependent on casinos or perhaps view them as an elixir to their financial woes, Carlyle asserts that gaming must be seen as just a piece of the tribe’s broader economic development.

“Gaming may not be here forever,” she says. “So we have to be able to look back and say that we spent the money wisely.”

To that end, she views her job as seeing the big picture and ensuring that gaming proceeds are invested in ventures that will reap long-term benefits for the community, such as scholarships, public safety, infrastructure and housing.

But Carlyle doesn’t deny that the casino has greatly broadened the economic and employment opportunities available to tribal members.

“Before the casino, the only job opportunities were either in farming, limited jobs within the community or going somewhere else,” she explains.

After opening in 1994, Harrah’s Ak-Chin Casino—which now has a hotel, restaurants, a bingo hall, a golf course, an entertainment venue and convention space—has provided a lifeline to members of the tribe who would otherwise be relegated to farming or leaving the community altogether to search for work.

She views her current role on the five-member Ak-Chin tribal council as that of a steward and as an elder who brings stability, leadership and wisdom harvested from past generations.

Though she will become a great-grandmother in June, Carlyle shows no signs of slowing down. In 2016, she completed her associate’s degree at Central Arizona College and plans to continue at Arizona State University studying public health.

“Most of my fellow classmates could have been my grandchildren!” she jokes. “Some of the professors could have been my grandchildren!”

—Aaron Stanley

Following Her Star

Angela Dauphinais, Players Club Manager, Valley View Casino Hotel

Angela Dauphinais has come a long way in her career—literally.

Angela Dauphinais has come a long way in her career—literally.

Starting in the frozen north—Bemidji, Minnesota, home of no less than three Indian reservations—she crisscrossed the continent in search of opportunity, and found it in abundance in the field of tribal gaming.

A member of the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians, Dauphinais learned early the importance of tenacity, hard work and following her star. After earning a bachelor’s degree in marketing and then her MBA, she relocated to Lexington, Kentucky for a job selling commercial kitchen equipment and became the leading salesperson in the nation in less than a year.

In her first job in gaming, at the Spirit Lake Casino & Resort in St. Michael, North Dakota, she rose from promotions manager to marketing manager and eventually led multiple departments.

“I was capable, eager and enthusiastic,” says Dauphinais. “They were very willing to reward me with more responsibility, and I welcomed it.”

Her tenacity was tested in 2008, when she and her husband Dean, a former Marine, decided to relocate again to Southern California.

“We took a chance and moved there without jobs,” Dauphinais recalls. “As we were driving cross-country in our U-Haul, the stock market crashed and the country basically flipped upside down.”

With characteristic resilience—and nonstop networking—she soon found a new home at Valley View Casino and Hotel in San Diego, owned and operated by the San Pasqual Band of Mission Indians. Beginning as manager of bus transportation, Dauphinais rose through the ranks to become players club manager in charge of a 35-member team (she still leads the bus program). In the most competitive Indian gaming market in the U.S.—San Diego has nine tribal casinos—her department has consistently ranked tops in hospitality.

Again, Dauphinais credits her success—and her quick succession through the ranks—to the work ethic forged in her youth.

“Tribal gaming opened the door for me,” she says, “but after you get your foot in the door, it’s how you deliver and perform, because in this business, you’re up against a lot of great professionals.”

—Marjorie Preston

Blazing a Trail

Janie Dillard, Executive Officer of Operations, Choctaw Nation

As a girl growing up in rural Oklahoma, Janie Dillard barely acknowledged her Choctaw heritage. “I didn’t want to be a Choctaw,” she says. “I didn’t want to claim any degree of Indian blood.”

As a girl growing up in rural Oklahoma, Janie Dillard barely acknowledged her Choctaw heritage. “I didn’t want to be a Choctaw,” she says. “I didn’t want to claim any degree of Indian blood.”

At the time, the nation relied almost completely for subsistence on the U.S. federal government. Proud and independent, Dillard wanted nothing to do with relief checks, food stamps and free clinics. “I can remember sitting in the tribal clinic, seeing kids barefoot and in bad clothes, and thinking, ‘This is awful.’”

Then Dillard’s father, whom she has described as her mentor and hero, made a prophetic statement: “I guarantee there will come a day when you see this tribe flourishing and growing into the corporate world.”

“I couldn’t even visualize that,” says Dillard.

But in time, she helped to make it happen.

In the early 1980s, Dillard’s father urged her to apply for a government job, and in 1982, she began her career as secretary for community health. In 1984, she transferred to the Women, Infant and Children program, where she eventually rose to director.

In 1987, when the tribe launched its high-stakes bingo operation, Dillard was first in line for a job. She began as floor manager at the Choctaw Bingo Palace. “I remember our grand opening. It was exciting, scary and challenging all at once.” Because the kitchen wasn’t ready to open, “we had to go get chicken from down the road.”

“We embraced it,” she says. “We didn’t let ourselves become defeated. We never dreamed what gaming would do for our tribe.”

As the enterprise expanded, so did Dillard’s influence. She rose through the ranks to become advertising director, then general manager, then director of gaming.

In October 2001, she became executive director of gaming for what has grown into a multimillion-dollar enterprise with eight casino resorts.

While the industry has created abundance for many tribal members, Dillard acknowledges there are some areas where the lack she knew as a child is commonplace.

“There’s so much growth potential in every department of our tribe, yet there is poverty out there in the more rural isolated areas—it still exists, to this day. One of our main goals is to bring new jobs into rural communities, open up satellite offices and bring in some new industry. Indian Country is still a land of opportunity, and as a tribe, we’re opening new windows and opportunities every day.”

—Marjorie Preston

Class Act

Francine Dupuis, Treasurer, S&K Gaming LLC

When it comes to Indian casinos, biggest may not always be best. So says Francine Dupuis, former gaming commission chairwoman for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of Montana and treasurer of S&K Gaming LLC.

When it comes to Indian casinos, biggest may not always be best. So says Francine Dupuis, former gaming commission chairwoman for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of Montana and treasurer of S&K Gaming LLC.

While some tribes command multibillion-dollar gaming enterprises—the Mohegans, the Mashantucket Pequots, the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux—last November, Dupuis’ people were excited to open a new Class II gaming hall on their Flathead reservation near Missoula.

The $21 million Gray Wolf Peak Casino, which replaces a smaller facility of the same name, is dwarfed by the tribal mega-resorts like Foxwoods, Mohegan Sun and Mystic Lake. Even so, says Dupuis, the 34,000-square-foot gaming hall and its sister property, KwaTuqNuk Resort & Casino in Polson, are consistent moneymakers that create steady employment for hundreds of tribal members.

In Dupuis’ view, the casinos’ Class II status in some ways may be preferable to Class III, and may be a purer expression of tribal sovereignty. “When you can’t reach a compact agreement with the state, you can say, ‘OK, state, we’re at a deadlock. We will just go to Class II. That is our right.’”

The CSKT’s last Class III gaming compact lapsed in 2006 when negotiations with the state broke down. The benefit of Class II is clear. Because Montana allows Class III machines at any business with a liquor license, going to Class II allowed the tribes to sidestep intense competition from scores of gas stations, restaurants and roadside mom-and-pops. In addition, they can offer everything from penny machines to multimillion-dollar progressives, while jackpots at state-licensed facilities are capped at $800.

As the National Indian Gaming Commission noted in a 2015 report, almost 60 percent of tribal gaming halls generate less than $25 million in gross gaming revenues per year. Yet those facilities are vital contributors to economic development on reservations.

Like the tribal casinos, Dupuis, a mother, grandmother, rancher and tribal education activist, believes smaller is better in family life too.

She grew up in the tiny town of Elmo, Montana (population: 143) in a home with no running water, where many neighbors did not have electricity. She says tribal gaming, along with the tribe’s hydroelectricity and timber operations, technology firms and other ventures, all contribute to improve the lot of her people.

“Some bigger tribes make megabucks with Class III and a compact, but tribes need to understand Class II is just as important,” says Dupuis. “Always keep an eye on Class II and Class II issues. That is how Indian gaming started.”

—Marjorie Preston

East Meets West

Kara Fox-LaRose, Chief Executive Officer, ilani Casino Resort

For Kara Fox-LaRose, entry into the gaming industry was directed by her father, a member of the Mohegan tribe. And the rest is history.

For Kara Fox-LaRose, entry into the gaming industry was directed by her father, a member of the Mohegan tribe. And the rest is history.

“I was hired as the 33rd employee, about six months before we opened in Connecticut,” she recalls. “And I’ve been with the company ever since; I just celebrated 21 years. I was able to grow my career as the Mohegan brand developed.”

Fox-LaRose left a job with a law firm in Boston to follow her dream.

“I was doing some support and administrative work for the office,” she says. “It was a smaller firm that was quite successful, but at that point in my life, I really wasn’t sure if that was the right path… So I was fortunate to find Mohegan Sun—and what an amazing ride it’s been.”

Working with the tribe was also very gratifying to Fox-LaRose because it was benefiting her tribe.

“Being part of a company that truly is about the roots—humanity, about people,” she says. “And it’s really about how we treat each other. It’s about being welcoming, and mutual cooperation, and building relationships, and being respectful.”

And that’s why she was so pleased to get the assignment to lead the casino project for the Cowlitz tribe in southwest Washington, just north of Portland, Oregon. The Cowlitz hired the Mohegan Tribal Gaming Authority to build and operate their casino.

“That’s something that the Cowlitz believed in, as well,” she says. “Building ilani—about to open in just a couple of months—they believed in the Mohegan management philosophy, because it’s how the tribe survived all those years.

“This has been an amazing opportunity, and working with another tribe now brings a different dynamic to the mix. These two tribes are very much in alignment with who they are and their core values. And so we are very fortunate to work with great people.”

Before setting sail for Washington state, Fox-LaRose says the background she developed at the Mohegan Sun casino in Connecticut, and as assistant general manager at Mohegan Sun Pocono, laid the groundwork for her new job.

“Mohegan Sun in Connecticut is one of the largest properties in the world, so the volumes of people that come into the doors daily prepared me for what we’re doing here,” she says.

“This is an opportunity for me to really create a team with great dynamics among the group. These good people are people who really want the best for the tribe. They’re excited about the project, and I think pulling together that team is going to make this project successful.”

—Roger Gros

Learning While Doing

Eric Geisler, Vice President, Tribal Gaming Student Association, San Diego State University

At 29 years old, Eric Geisler has grown up enjoying many of the positive benefits that tribal gaming has brought to Southern California.

At 29 years old, Eric Geisler has grown up enjoying many of the positive benefits that tribal gaming has brought to Southern California.

Despite hailing from the non-gaming La Jolla band of Luiseño Indians in Southern California, he credits the emergence of casino gaming among neighboring tribes as having radically transformed the quality of life in the region—touching everything from public safety to economic development to tribal governance.

“Before tribal gaming, the types of jobs offered on the reservation were strictly grant system jobs,” Geisler says. “What that left us with was seasonal employment, which really hasn’t helped tribes prosper or reach self-determination and self-reliance. Gaming is really what has changed that.”

Witnessing these impacts firsthand sparked within him a passion to be a torchbearer for tribal gaming in his community moving ahead.

“I have such a passion for economic development, and gaming specifically, because of the revenue that it provides to tribes to better their people,” he explains. “It’s a leap towards a more prosperous life for native culture.”

Geisler is currently enrolled at San Diego State University, where he is vice president of the Tribal Gaming Student Association and is slated to graduate in May 2017 with a dual degree in American Indian studies and tribal gaming. He credits the SDSU-Sycuan Institute on Tribal Gaming as the springboard that has helped him and other students kick-start their careers.

Geisler is also getting a taste of real-world experience through his work on a proposed $300 million-$400 million expansion project at the Morongo Casino in Cabazon, California. Brought on by a mentor—John James, the casino’s chief operating officer who was looking to recruit young native talent—Geisler is now learning the ins and outs of how and why a gaming facility is designed and constructed the way that it is.

After the Morongo project, Geisler hopes to transition into the day-to-day aspects of running a tribal gaming business.

But even as Geisler overflows with passion for his line of work, he is concerned by what he sees as tribal members not fully capitalizing on the employment opportunities that gaming offers.

“Tribal gaming has been very successful as a whole, but what you don’t see a lot of is native people being the frontrunners on the operations of these facilities that are adding so much to our communities,” he says.

“I’d encourage natives to get out there and get involved with the industry,” he says in a clarion call. “There’s ample opportunity out there.”

—Aaron Stanley

The Path Home

Jared Munoa, First Vice President, Pechanga Development Corp.

Historically, many Native Americans have looked for ways off the reservation. Today, some are finding reasons to return.

Historically, many Native Americans have looked for ways off the reservation. Today, some are finding reasons to return.

In 1978, Jim Munoa, of the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians, relocated his young family, including 5-year-old son Jared, from San Diego to the tribe’s reservation in Temecula. Though Jared Munoa would go on to pursue careers off the rez—in retail, sports training, consulting and real estate—in recent years he, too, found his way back.

“I had worked in all these different industries and was able to succeed as an individual and as a businessman,” Munoa recalls. “From there I was ready for a change. I wanted to come back, help my tribe out and reinvent myself.”

In 2015, Munoa was elected first president of the Pechanga Develop-ment Corp. Since then, he has presided over the $300 million expansion of the tribe’s Pechanga Resort & Casino, which broke ground in December of that year and is expected to be complete by this Christmas.

The investment is more than justified, Munoa says. The resort, which opened in 2002, is consistently 100 percent occupied with a lengthy waiting list, and even in slow months is forced to turn away thousands of would-be guests. The expansion will add a four-diamond hotel tower with almost 600 rooms, a convention center, spa and other amenities.

A hands-on leader, Munoa has been deeply involved in almost every aspect of the expansion, “from picking out the tile for the pool area to choosing how the valet is going to be positioned on-property to working with civil engineers and determining how we’re going to step into the future with our branding,” he says. “I have a 30,000-foot-view of the overall expansion, and also see to the small details such as the carpeting, wall coverings, fixtures and everything in between.”

He has overseen the growth of the tribe’s onsite retail assets and RV park, and is weighing development plans for additional land holdings in Southern California. And in 2016, he oversaw the launch of Best Bet Casino, the casino resort’s free online gaming app.

“From my perspective it’s a way to market our brick-and-mortar casino, reach out regionally to those who may not know our brand, and then of course, expand the name of Pechanga on an international level,” says Munoa.

Though the reservation is still not heavily populated, “there are more individuals moving here,” says Munoa. “They come for the benefit of connecting culturally, and also taking advantage of the opportunity we’ve been able to create in this valley.”

—Marjorie Preston

Journey Starts With One Step

Kelly Myers, Chairwoman, Oklahoma Tribal Gaming Regulators Association

The idea of working in tribal gaming never crossed Kelly Myers’ mind when she was growing up in Oklahoma and studying accounting at Oklahoma State University.

The idea of working in tribal gaming never crossed Kelly Myers’ mind when she was growing up in Oklahoma and studying accounting at Oklahoma State University.

“I always thought that I’d go to work for an auditing firm or be an accountant and move up that way,” she says, intending to follow in her mother’s footsteps.

But that all changed in 2003 when she was recruited by her native Iowa Tribe to serve as a jack-of-all-trades auditor and licensing agent while the groundwork was being laid for the 2005 compact that would bring Class III tribal gaming to the state of Oklahoma.

“I had never been in a casino, so it was a whole new journey for me,” Myers says. “I loved it. I’m still passionate 14 years later about my job.”

In 2008, she moved over to the Cherokee Nation Gaming Commission, where she continues to serve as a licensing and compliance manager. She also serves as chairwoman of the Oklahoma Tribal Gaming Regulators Association, chairwoman of the gaming commission of the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma, and a board member of the National Tribal Gaming Regulators Association.

“It’s been never-ending,” Myers says. “I always tell people that there’s always an opportunity, whether in accounting or management, or on the operations side, security, tribal government. There are so many parts of gaming.”

As a regulator, Myers takes pride in helping the 34 gaming tribes and 180 facilities in Oklahoma maximize the benefits of gaming while ensuring they are in compliance with federal, state and local regulations—not always an easy task.

“We’re what you could say are the tribal police—a necessary evil. It’s always a hard job making sure that we’re all doing the right thing,” she says. “But we’re all here for one thing, and that’s to ensure our tribes and our nations are benefiting from these casinos and that we’re maintaining the integrity of our facilities.”

Within her native Iowa Tribe, she says programs funded by gaming proceeds now go toward incentivizing kids to graduate from high school, go to college, return with advanced skills and eventually buy a house.

Myers, a single mother, is also thankful that her career has allowed her to serve as a powerful role model for her 11-year-old daughter.

“It has allowed me to have a great career to support and take care of my daughter,” she says. “It has allowed me to show her that you can still go for your goals and your dreams no matter what.”

—Aaron Stanley

World of Words

June Shorthair, Media and Public Relations Manager, Gila River Indian Community

In the world of tribal gaming, marketing and communications can be just as nuanced and crucial as casino-floor operations.

In the world of tribal gaming, marketing and communications can be just as nuanced and crucial as casino-floor operations.

Just ask June Shorthair, who currently manages communications and public affairs for the Gila River Indian Community, located just south of Phoenix.

Shorthair began working as a media and public relations manager for Gila River in 1997, and within a few years had assumed responsibility for marketing operations at all three of the tribe’s casinos.

But in the early days of tribal gaming in Arizona, understanding and complying with federal and state regulations meant that marketing was a tad more complex than your standard television ads, mailers and promotions.

“Marketing was always a real strong component to the business operations. In the beginning, it was key to understand some of the nuances of gaming in Arizona and the new regulations that they wrote as they pertained to how we marketed,” Shorthair explains.

For Gila River, she stresses, a successful gaming enterprise had to not only possess sound business fundamentals and compliance protocols, but also reflect the preferences and views of individuals within the community.

“Whatever promotions you give, whatever strategies you put in—you had to make sure you had looked at all three entities,” she says. “You couldn’t look at just one or the other. You can’t be just market-driven, because a lot of times the other entities don’t follow along with that same focus.”

Shorthair stepped down in 2008 to tend to an illness in the family, but not before she showed consistent revenue increases that prompted expansion efforts at all three properties.

It was also a source of personal pride being one of just two Native American marketing directors working in tribal gaming in Arizona at the time. “I took that as a great challenge,” she says.

While she no longer directly works in the tribal gaming sphere, she still brings her marketing and business acumen to the Gila River tribe—where she is responsible for social media, website, newsletters and public outreach efforts.

She credits her array of work experiences inside and outside of tribal gaming as giving her the tools necessary to advance the tribe’s interests.

“I’ve worked with five or six different CEOs, about seven different directors of marketing. I’ve learned what not to do mostly, but I also learned to develop best practices,” she says. “I’ve learned to listen and then create solutions. I’m the kind of person that’s saying ‘let’s go—what are we going to do to get it done?’”

—Aaron Stanley

Rising to the Challenge

Christinia Thomas, Deputy Chief of Staff, National Indian Gaming Commission

Among her peers in tribal gaming, Christinia Thomas has always run ahead of the pack.

Among her peers in tribal gaming, Christinia Thomas has always run ahead of the pack.

The Sandstone, Minnesota native, a member of the Mille Lacs band of Ojibwe Indians, got her first casino job the day after her 16th birthday, working the buffet at the tribe’s Grand Casino in Hinckley. By 18, she had transferred onto the gaming floor. At 19 she was a supervisor.

When she moved to the Casino Mille Lacs in Onamia, across the street from the tribe’s legislative branch, Thomas shifted from gaming to government, and never looked back. With zero legal background, she was hired as a legislative assistant, a position she held from 1999 to 2004. During that time, she embraced her tribal culture as never before.

“As a kid I was not actively involved in the tribe because I wasn’t raised on the reservation,” she says. “I always took part in tribal powwows, and my mom taught me how to bead when I was 5, but I didn’t fully understand the significance of those traditions and many others until I was in the legislative position.”

When the tribe decided to rewrite its gaming ordinance, the job fell to Thomas. “They said, ‘You worked in gaming—here, write this.’ The secretary treasurer at the time had a lot of faith in me, more than I had in myself. I got a lot of support from the other elected officials too. They just pushed me.”

She accepted the challenge, the first of many. As the tribe prepared to split its gaming management and regulatory functions, again Thomas was tapped for a key role on the five-person regulatory authority board.

“I was 28 years old, but I never told anybody. I wanted people to take me seriously.”

She held the position until 2012, concurrently serving as tribal delegate for the Mille Lacs Band as a member of the National Tribal Gaming Commissioner/Regulators. In 2011, Thomas was appointed to the tribal advisory committee of the National Indian Gaming Commission, and in 2013 became NIGC’s deputy chief of staff.

Today, amid the hurly-burly of Washington, D.C., Thomas still enjoys a good challenge. “When you think about it, I once had two casinos to oversee, and now I have almost 500. I’m able to help tribes make sure the integrity of their floors is being met and be the agency expert who answers their questions. I get the best feeling being in this position, a feeling of personal satisfaction that what I learned at my tribes’ gaming facilities has given me the expertise to help others.”

—Marjorie Preston

One comment on “Faces of Indian Gaming”

Comments are closed.