Tribal gaming has created opportunities for Native Americans across the United States and Canada. States like Minnesota, Washington, Oregon, California, Connecticut, Florida and many others have tribal gaming. But there is one state that was actually reserved for Indian tribes that was late to the game, but has made a tremendous impact across Indian Country.

Oklahoma was designated by the United States in the 1820s and ’30s as “Indian Territory.” While trying to remove tribes from the southeastern states to make room for settlement, the U.S. government forced the tribes to move from that region to Oklahoma in the infamous “Trail of Tears” march. Thousands died, families were torn apart, and Oklahoma was essentially a foreign land already occupied by different tribes.

But even Oklahoma wasn’t safe. Once envisioned as a state for Native Americans called “Sequoyah,” Oklahoma’s increasing arrival of white settlers was encouraged by a land rush in 1889 that opened tracts for settlement. Those who arrived early were called “sooners.”

The discovery of oil and natural gas became the main thrust of the state’s economy, which is still the case today.

Despite the land rush, Indian reservations still made up large swaths of the state. Dozens of tribes lived for generations in poverty, while the energy companies made a fortune on adjacent land. The Cherokee, the Creek, the Chickasaw, the Choctaw and the Seminole Indians, who were known from the early 1800s as the Five Civilized Tribes, dominated the government-to-government relations through the years. But contact was limited, and offered little benefit to either side.

But it was a slump in the energy business that provided an opening for the tribes. When tribes began to realize that bingo provided an opportunity for revenue generation in the 1980s and ’90s, Oklahoma tribes were quick to join in. By 2000, the operations became substantial as technology grew quickly, providing tribes with electronic games that mimicked traditional bingo.

B-I-N-G-O

John Tahsuda, an attorney with Global Navigator, a former general counsel for the U.S. Senate Indian Affairs Committee and a member of the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma, believes it was the passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988 that began the long change.

“IGRA presented a wide definition of bingo and that included a wide variety of games,” he says. “In Oklahoma, the tribes took advantage of that latitude in descriptions right from the start. When it was passed, everyone thought it was about bingo. Few people had any idea how broadly it would be applied to all forms of gaming.”

It was competition with other gaming states that caused the quick advancement of the industry in Oklahoma, once the compact was struck with the governor.

Today, Oklahoma has the second-highest grossing gaming revenue in Indian Country, $2.8 billion (after California at $7.3 billion). With 110 facilities (most of them smaller slot parlors, convenience stores, travel plazas, etc.), Oklahoma also has the most tribal gaming operations in the country.

The enlightened attitude of the tribes and state government is one of the primary reasons for this ascension in facilities and revenues, according to David Schwartz, director of the Center for Gaming Research at the University of Nevada Las Vegas.

“Oklahoma has really shown what can happen when you put a premium on gaming,” says Schwartz. “From the start, Oklahoma has profited from the untapped market that is Texas and Kansas-until recently, that is. It shows what can happen when you have the full support of state government.”

Compact Negotiations

When energy prices slumped in the early years of the 2000s, state government went looking for more revenue and made efforts to diversify the state’s economy so it would not be so dependent upon oil and gas. Tribes saw an opportunity not only to help the state through a budget crunch, but also to reach an agreement with the government that would mean better and larger facilities, more jobs and more revenue for the state and the tribes.

“Remember, Oklahoma didn’t even have a lottery for many years,” explains Tahsuda. “So when the economic slump came on us, the legislature was open to many options, and the lottery, relief for the state’s racing industry and tribal compacts were just part of the package. It was a chance for the tribes to achieve some certainty.”

Janie Dillard, executive director of gaming for the Choctaw Nation, says the larger tribes led the way.

“The Choctaw Nation gaming team was the leader in the process by bringing together the horsemen and state members to write and develop the plan for advancement,” she says.

In addition to the Choctaws, the Cherokees, the Creek Nation, the Apaches and many others were involved in the compacting process. Because tribes had good relations with the government, the process went relatively smoothly.

“The Chickasaw Nation has always had a very positive and productive relationship with the state of Oklahoma,” says Governor Bill Anoatubby of the Chickasaw Nation.

Tahsuda says the compact was an enlightened piece of legislation that had a greater impact than was first imagined.

“Our revenue sharing model is one of the lowest in country,” he says. “It enables the tribal gaming industry to be a vital force in the economy of the state, especially in the rural areas. In some cases, it’s the main economic generator for that area and has contributed to the building of infrastructure such as roads and hospitals. It’s a real market force that helped the state diversify from the oil and gas industry.”

John Berrey, chairman of the Quapaw Tribe, owners of the Downstream Casino Resort in the northeastern corner of the state, says even though the relationship wasn’t bad between the tribes and state government, the gaming compact has made it even better.

“Tribes have been in Oklahoma since long before statehood in 1907,” he says. “But there was never a real well-established relationship between the tribes and the governor’s office. Today, we have a great relationship with the governor and the legislature. The environment in Oklahoma City is very positive to Indian Country.”

Tahsuda agrees with Berrey.

“There’s still a healthy tension between the state government and the tribes,” he says, “but Indian gaming really brought them together. While Oklahoma City and Tulsa got the benefit of that diversity, it’s the rural county officials who really work closely with the tribes, because that’s where the impact is.”

Communities Come Together

While most of the Oklahoma casinos are centered in Oklahoma City, Tulsa or along the Texas border, the rural areas of the state have done very well because of tribal gaming. The Quapaw Nation in the far eastern corner of Oklahoma is a good, but unique, example.

“Our driveway is in Missouri, our parking lot is in Kansas and our casino is in Oklahoma,” laughs Berrey.

He says the tribe’s commitment to the community is an important aspect of everything it does.

“It is crucial to our business plan,” he says. “We’re probably the biggest donor to charitable organizations in the four-state region. We have a lot of interaction with the hospital. We’ve adopted the women’s center and provide flowers on a daily basis. We work with people in need. We do a lot of things that involve us with the town and the region. We have a pavilion and meeting space that have become the center of conferences and meetings for the region.”

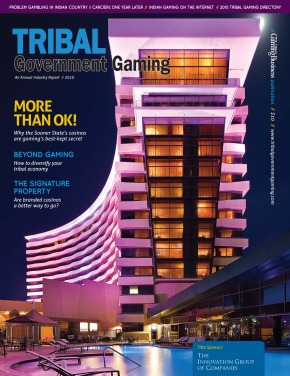

The Choctaws, who just opened a new Las Vegas-style resort in Durant near the Texas border, have used gaming to help the tribe and the surrounding communities.

“Our gaming facilities alone employ 40 percent Choctaw members,” says Dillard. “We also employ and have built organizations such as medical clinics, hospitals and other programs. These opportunities would not have been so quickly achieved without the advent of gaming. This has enabled the Choctaw Nation to become more self-sufficient, and independent of the federal government. Many of our tribal members have grown with our organization to become part of senior management throughout our facilities.”

Dillard says Choctaw casino executives participate in the communities in which they work, including local chambers and charities.

“We have contributed on average, over the past five years, $3,135,990 to charitable organizations,” she says. “We support 10,000 jobs in the state of Oklahoma as well as 5,000 outside the state. We spend $5 million to $6 million annually on roads within Oklahoma. Our 2009 fiscal year spend included $28,286,685 in contributions for police and fire departments, county, city, schools, churches and scholarships. Scholarships have grown to about 5,000 per year.”

Anoatubby says the Chickasaws are also committed to helping the community.

“We believe it is very important to be good neighbors,” he says. “We have productive partnerships with state and local governments, community organizations, schools and other organizations which enhance the lives of all citizens. The Chickasaw Nation works closely with a number of charitable organizations. In addition to monetary donations, we encourage employees to donate time and talent to several organizations including the United Way, Red Cross, March of Dimes and Relay for Life, to name a few. The Chickasaw Nation also partners with state, county and municipal governments for the construction, repair and maintenance of roads and bridges.”

For Berrey, the economic development brought by Downstream has helped the tribe by providing jobs for any member that wants one.

“When I first became chairman eight years ago, we had 89 employees,” he explains. “Today, we have nearly 2,000 employees. That’s not only brought a lot of jobs to our tribal members, but it’s brought some revenue to the tribe. Part of our bond financing only allowed for a certain amount of money to go to the tribe, but even that has made a big impact. For the first four years, we’re committed to paying the interest on the loans. After that four years is up, we plan on restructuring the debt and sending even more money to the tribe.”

Competitive Pressures

With 110 facilities and growing-not counting gaming establishments active and planned in surrounding states-competition in Oklahoma is getting fierce. While most casinos have niche markets, the larger ones are depending on a broader appeal.

The new Choctaw casino was built in Durant, site of the Choctaws’ first foray into gaming, because it is a proven location.

“Due to its location, the facility has advanced as the premier casino throughout our 10 and a half counties,” says Driscoll. “It has the largest populated area from which to draw and was the natural selection for the beginning of the facilities to be developed with such offerings as the current amenities. We maintain a total of seven casinos, and have incorporated gaming centers within 11 of our 13 travel plazas.”

For the Quapaws, the Downstream facility has become the state-of-the-art casino within a hundred miles. Berrey says he was not convinced that a full-blown casino resort was necessary in the beginning.

“At first, I just wanted to put up a big metal building and put some slots in there to generate some revenue,” he says. “But it was from talking to people like (Downstream developer) Mickey Brown and (Quapaw Vice Chairman) J.R. Mathews I came around to the idea that we had to think big. We got our business committee on board and we went full tilt.”

Although not far from Tulsa, the tribe decided to aim away from that population center.

“Our objective was to go east, not west,” says Berrey. “Originally about 5 percent of our market was projected to be from Tulsa, and we might get 10 percent now, but we really focused on the northwest Arkansas corridor of Fayetteville and Bentonville. Springfield, Missouri, is a big market for us. And the towns that are south of Kansas City are also a market.”

One of the most unique casinos in Oklahoma is the Chickasaws’ WinStar World Casino. Visitors get tastes of Rome, Venice, London, Paris and Beijing all under one roof-or one tent, you might say. WinStar World includes façades of these international destinations, with the interiors located inside stressed membrane structures. A traditional hotel with 395 rooms and suites lies adjacent to the casino.

Bill Lance, the administrator for the Chickasaw Nation Division of Commerce, says there was a reason the tribe constructed the fifth-largest casino in the world.

“The idea behind the WinStar expansion was to create a destination,” he says. “We wanted to create the most unique, beautiful and dynamic casino space this side of Vegas for destination status, and we’re doing that with WinStar World Casino.

“WinStar is quickly establishing itself as a destination resort, attracting patrons and convention business from across the U.S. So, we have positioned ourselves to compete with major cities across the country, not just Texas and the surrounding states.”

Market Saturation?

Because of the increased number of gaming facilities-nine were added in the difficult year of 2009 alone-there is some question about how much more gaming Oklahoma can absorb. And opinions differ according to tribe.

For the Choctaws, the keys are product and service.

“We are competitive in the market and will continue to strive to offer outstanding guest services,” says Driscoll. “We focus on providing superior product along with the respect our guests deserve. We offer exciting games and amenities such as hotel, full-service spa and variety of food venues as well as retail options. We will listen to our guests and use technology to meet the needs of the future.”

Driscoll says they monitor the business on a day-to-day basis.

“There are segregated areas of the state that are beginning to show signs of saturation,” she says. “Each organization should be cognizant of business needs and demands so as to not cannibalize ourselves. We continually monitor business levels and adjust accordingly.”

Berrey believes that there is room for expansion in some areas of the state, but he’s not worried about increased competition in the Downstream market.

“The south is pretty full going after the Texas market,” he says. “There’s some opportunities in the Highway 35 corridor between Wichita and Oklahoma City. But what we provide is unlike almost any facility in the state. We’re almost elegant. We have an incredible staff that’s friendly and outgoing. It would be very difficult to duplicate what we have. Our competitive advantage is in our facility and our customer service.”

For the Chickasaw Nation, the keys are diversity and preparations for businesses beyond gaming.

“Our long-term goals in gaming are built with competition in mind-not only from other casinos, but online gaming as well,” says Lance. “However, our response to that is to diversify our business portfolio and invest in the manufacturing, energy and health care arenas.”

Anoatubby says the tribe is well down that road.

“The Chickasaw Nation owns a diversified and growing portfolio of more than 60 businesses that employ more than 11,500 individuals and produce annual revenue of approximately $750 million,” he explains. “In addition to its gaming facilities, the nation owns Bank2 in Oklahoma City with $90 million in assets; Solara Healthcare LLC, operating eight hospitals in Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana with more than 1,000 employees; Chickasaw Nation Industries Inc. with more than 2,000 employees providing administrative, technical, construction, medical and information technology services to federal agencies; Bedré Fine Chocolate, which produces chocolates for corporate clients and upscale stores; five radio stations located in the Ada area; and a utility company that provides electric, water, sewer and natural gas services.”

The Choctaws have also been developing diversified businesses.

“The Choctaw Nation has been working diligently to ensure diversification within our business programs,” says Driscoll. “We have the vision and foresight to continue the growth of the Choctaw Nation and the success of its endeavors. Choctaw Management Services Enterprise has enabled the expansion of health care services, social programs and educational assistance. Texoma Print Services manages a commercial printing facility that also produces promotional items. Choctaw Manufacturing Development Corporation operates two certified manufacturing facilities within Oklahoma. Choctaw Nation is also involved with land and cattle management. We also farm, and grow hay and pecans for reinvestment. Furthering the economic development is a priority when considering our investments.”

When compared with those two tribes, says Berrey, the Quapaws are only just beginning.

“We are at the stage now that we are just looking to diversify to see where we can grow,” he says. “We want to put more dollars into health care and elder care, wellness centers, while at the same time looking for new business. The other tribes are a little further along than we are at this point. We spend a lot of time talking to other tribes. We all work together.”

Tahsuda believes that saturation will force tribes to consider other businesses.

“It is now a mature market,” he says. “There’s still room for growth but the tribes must now compete with out-of-state casinos more and more. And there are still a lot of needs in Indian Country, so gaming must grow stronger and diversify.”