this is where we have current news updates

Article Tag: has_thumbnail

Gambling on Energy

Chairman Carl Venne of the Crow Nation of Montana, testifying before a May 2008 meeting of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, had a clear vision for his nation’s 12,000 citizens, many of whom reside on the tribe’s remote, 9 million-acre reservation. The future, he said, lies with the more than 10 billion tons of high-grade coal on Crow lands, about 3 percent of the world’s coal resources.

“Given our vast mineral resources, the Crow Nation can, and should, be self-sufficient,” says Venne. “My administration desires to develop our mineral resources in an economically sound, environmentally responsible manner consistent with Crow culture and beliefs. Crow people are tired of saying we are resource rich and cash poor.

“My larger vision,” Venne said, “is to become America’s energy partner and help reduce America’s dependence on foreign oil.”

Some 500 miles away in Belcourt, North Dakota, Jessie Cree, an elder with the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, spoke of his tribe’s plans to harness energy generated by winds that blow over the vast prairie.

“It has spirituality,” Cree told the Boston Globe newspaper. “You can’t see the wind blow, but you can see whatever it hits… the old people that were spiritual, they were able to see the wind. They would be able to see the spirit of the wind.”

“Wind blowing through Indian reservations in just four northern Great Plains states could support almost 200,000 megawatts… enough wind power to eradicate all fossil fuel-burning power plants in the U.S.,” said environmental activist Winona LaDuke, a Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) from Minnesota.

Whether it is the winds that blow in the North, oil and gas in the Great Plains or coal, uranium and solar power in the West and Southwest, American Indians are close to reaping huge economic gains from the voluminous energy resources on largely remote tribal reservations.

U.S. Department of Energy experts believe 10 percent to 14 percent of the nation’s traditional fossil fuels, gas and renewable energy resources can be found on the 59 million acres that make up the country’s Indian reservations, land held in federal trust and deeded to tribal governments and individual tribal citizens.

The first Americans intend to utilize those resources in an environmentally friendly manner that respects cultural and spiritual beliefs and respect for the land.

Perhaps most important, tribes view ownership and management of energy resources as a means of strengthening sovereignty and self-governance and building the foundation for a sustainable future for future generations.

With President Barack Obama’s pledge to reduce the country’s dependence on foreign oil, the nation’s indigenous peoples are poised to reap billions of dollars in energy production in the coming decades. Some predict revenues will exceed the nearly $27 billion tribes generated in 2007 from government casinos.

“Maybe not in the next 10 years, but in the next 20 years, yes, I believe it will,” says A. David Lester, executive director of the Council of Energy Resource Tribes of Denver, Colorado, and a citizen of the Muscogee Cree Nation.

There is justice in the energy opportunities in Native America as most tribes with conventional and renewable energy resources are located on remote reservations and have not benefited greatly from casinos. Seventy percent of revenue from tribal gaming is generated by 15 percent of the Indian casinos owned by small tribes in urban areas.

DOE geological surveys estimate there are 5 billion barrels of oil, 37 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and 58 billion tons of coal on Indian reservations. About 25 percent of the known onshore oil and gas resources are on tribal lands. Yet only about 4 percent of the tribal energy resources are in production.

In terms of renewable resources, geological experts say of the 360 reservations in the lower 48 states, 118 have biomass potential and 77 have wind resources.

The full potential of energy resources is difficult to gauge. Of the 15 million acres of potential tribal energy and mineral resources, only 2.1 million acres are being explored and developed.

“There are reserves in Indian Country we don’t know about,” says former U.S. Senator Benjamin Nighthorse Campbell, a citizen of the Northern Cheyenne Nation. “Only 30 percent of Indian Country has been adequately explored.”

New Tribal Paradigm

The opportunities in energy production on tribal lands extend far beyond economics, as great as they may be.

“Tribal leaders have a different vision of the future,” Lester says. “They view energy as a means of achieving more and stronger self-governance and a pathway to greater tribal prosperity. Energy is the means to achieve the goal, not the goal itself.”

A key component of President George W. Bush’s 2005 Energy Policy Act is the creation of Tribal Energy Resource Agreements, or TERAs, which enable tribes with adequate governmental structures greater authority in negotiating agreements with private utility companies and assuming ownership and management of energy production. The Southern Ute Tribe of Colorado, which owns a multibillion-dollar methane gas industry, is a prime example of what a tribe can accomplish when it controls its energy destiny.

“We believe TERAs will be a significant tool for tribes that would like to have more control over energy development decisions on tribal trust land,” says Robert W. Middleton, director of the Office of Indian Energy Economic Development. “There are several tribes that are already major players in domestic energy markets and we assume would take advantage of the additional flexibility of a TERA.”

Though well intended, Congress has not funded components of the Energy Policy Act to provide the education and training tribes need to build their capacity to own, manage and regulate energy development.

“There is no commitment from the federal government to build ownership and governmental capacity in Indian tribes,” Lester says.

It took 20 years for Indian tribes utilizing educational and training programs provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to establish and regulate environmental standards on tribal reservations. The U.S. Department of Energy must provide similar educational and training for energy resource tribes, Lester says.

As gaming tribes have been allowed to exercise their sovereign right to own, operate and regulate government casinos, energy resource tribes are seeking the opportunity to own, manage and regulate energy production.

“We need to open the door that allows Indian tribes to make significant contribution to the achievement of America’s national energy policy goals,” Lester points out.

Venne’s Vision

Although Venne died last month of heart failure, his vision remains. The Crow are partner with Australian-American energy in development of a $7 billion coal-to-liquids mine and plant project that would produce 50,000 barrels a day of clean diesel, jet fuel and naphtha. The project would create 4,000 construction jobs and 900 permanent jobs.

The Navajo Nation is close to beginning construction of a $3 billion, 1,500-megawatt coal burning power plant south of Farmington, New Mexico. The Desert Rock Energy Facility is expected to generate $52 million a year and create up to 400 jobs. Half the Navajo workforce is unemployed.

“Energy reserves on tribal lands represent the single largest source of untapped energy resources in the United States,” Navajo President Joseph Shirley says. “Tribal energy development is the future of U.S. domestic energy production as well as the future of tribal economic development. For Native nations the most pressing concern is the crushing poverty that renders impossible our dream of regaining our independence and preserving our language and culture. I believe the federal government and Native nations can come together as sovereigns and solve these problems in a mutually beneficial way.”

The Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara) of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota have taken steps to establish a TERA to expedite oil and gas leases on the nearly 1 million- acre reservation. There are 3.6 billion barrels of oil, 148 billion barrels of natural gas liquids and 1.85 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in what is known as the Bakken Oil Formation.

“We are poised at the brink of what could be the largest period of economic development in the history of the tribe,” says Chairman Marcus D. Wells Jr.

Renewable Strategies

About 100 tribes are exploring wind and solar energy, says Bob Gough, a founder of the Intertribal Council on Utility Policy, or COUP. Solar and wind energy resources in the Southwest and Great Plains are among the most abundant in the United States.

NativeEnergy partnered with the Rosebud Sioux of South Dakota in 2003 in building the first large-scale Native-owned wind turbine. The Rosebud Sioux and Citizens Energy Corporation of Boston, Massachusetts. have entered into a joint venture to develop a 100-megawatt wind turbine power project.

The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in Washington state is partners with Clipper Windpower of Carpinteria, California, on a plan to build a wind farm with up to 500 turbines. The tribe would eventually own and operate the wind energy company. The tribe also is planning to build a biomass energy facility at its Colville Indian Plywood and Veneer plant.

“Our goal is to bring benefit to the Colville Tribes while protecting and preserving our lands,” tribal energy coordinator Ernie Clark says. “The tribe is very excited about possible renewable energy developments, including wind.”

The Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate is developing a wind farm on tribal trust lands in northeast South Dakota.

The Blackfeet Tribe of Montana is working with Anschutz Exploration Corp. of Denver to find oil along the Canadian border. And Native American Resources Partner of Salt Lake City, Utah, is investing hundreds of millions of dollars in energy projects on two other Montana Indian reservations.

“We don’t invest in companies doing business in Indian Country,” NARP Vice President Lynn Becker told the Great Falls Tribune. “We partner with tribes on energy ventures in which we both earn an interest.”

The Chippewa Cree Tribe is working with NARP to develop natural gas or wind power on the Rocky Boy’s Indian Reservation. And the Assiniboine and Sioux tribes on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation are working with NARP to develop resources of some 60 billion barrels of oil.

“Right now, we’re working on a partnership to start our own oil and gas company that will allow us to do our own oil and gas drilling,” Fort Peck Tribal Councilman Rick Kirn says.

‘This Land is Your Land…’

When Woody Guthrie penned that iconic song, his intent was certainly not to exclude anyone, but give everyone a stake in what happens to the United States. His evocative lyrics brought together a sense of belonging for nearly all Americans.

Except perhaps for one group: the first Americans.

Yes, “this land is your land” but too often we forget who the land belonged to originally. From the $24 worth of trinkets for Manhattan to the “Trail of Tears” across the South, land from “the redwood forests to the gulf stream waters” was ripped from Native Americans in a way that can only be looked back upon with shame.

But those were different times, they tell us. Now, Native American land claims are handled in a more equitable and realistic manner.

If that is the case, however, how do you explain the recent Carcieri v. Salazar case by the Supreme Court? While some argue that the scope of the decision is limited to the Narragansett tribe and 32 acres of trust land in Rhode Island, the truth is that it has had much wider implications even before other land-into-trust circumstances get tested in other courts.

Some tribes have had to cancel projects scheduled to be built on trust land. Other casinos already on trust land are threatened with closure.

Congress will undoubtedly consider remedies to this unfair decision, but until then, Native Americans are once again questioning the wisdom and integrity of the U.S. government as it applies to land that they once wholly owned.

So it’s important to remember the last two lines of Guthrie’s song and how they may apply, once again, to Native Americans:

“And some are grumblin’

and some are wonderin’

If this land’s still made

for you and me.”

First Line of Defense

Gaming has become the single largest governmental revenue source for hundreds of tribes since the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act was enacted in 1988-yet despite that, many naysayers, almost always without direct experience with tribal gaming, doubt the wisdom of tribes overseeing their own gaming operations.

Yet tribal regulators are the first-and some would argue-the most effective line of defense in protecting the integrity of their gaming operations.

Of the three layers of gaming regulation, state, federal and tribal, the tribal element is the most important according to most tribes-not surprisingly! But is it true that the agency closest to the casino in question does the best job?

California Conflict

In California, the state agency in charge of regulating tribal/state gaming compacts and 58 casinos is the California Gambling Control Commission. Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger’s budget for 2008-2009 increased its number of officers from 70 to 83, to reflect the growth of tribal gaming in the state.

Yet one tribal gaming commission in that state, that of the San Pasqual tribe in San Diego County, whose executive director is John Roberts, has a staff of 52 to regulate Valley View Casino. That’s more than half of the amount devoted by the state agency to nearly 60 casinos.

Extend that same truth to the 400 Indian gaming establishments, operated by 230 gaming tribes all over the United States. In the sentiments of one federal regulator, it would take the states and federal government armies of regulators to perform the same job that the tribes perform.

But that didn’t stop the California Gambling Control Commission last October from aggressively trying to assert its authority by demanding “prompt access” to tribal casinos and their financial records. It also approved regulations that gave it the authority to inspect casino books, gaming operations, customer and employee access to cash, and the game integrity.

The commission said that it was filling a vacuum that had been created after a federal appeals court ruled that the National Indian Gaming Commission didn’t have the authority to directly regulate tribal gaming.

But those are all tasks currently performed by tribal gaming commissions.

As Howard Dickstein, an attorney who represents gaming tribes, observed at the time, “The dispute really isn’t about the standards. The dispute is over who has the authority to enforce them… The state apparently doesn’t have adequate respect for tribal governments and their gaming agencies’ independence. They’re managing to unite every tribe in the state of California against them.”

Roberts explains the split.

“To say we’ve had a difference of opinion is an understatement,” Roberts said. “We didn’t feel they had legal authority to do this. We screamed, ‘You can’t do it.’ And they said, ‘Yes we can.'”

In December the commission retreated from its stance. Tribes in California hailed the retreat as an admission, or at least recognition that the tribes already do a more-than-adequate job.

The tension between the California commissions and the gaming tribes is a dynamic that is played out in states and between tribes all over Indian Country.

Most tribes take their regulatory role very seriously. “Tribes take a tremendous amount of pride in their ability to regulate themselves,” says Tracy Burris, for many years a gaming commissioner with the Choctaw Nation in Oklahoma, and who a few months took up that job at Viejas Casino in southern California.

Is it justifiable pride?

“I understand what my culture requires me to do,” explains Burris. “It is important to me culturally that I have honor. It is the honor of the tribes that is important to them. Whether that is true of all of the people who work for us, I can’t say. But when it comes to self-regulation or governance our honor is important to us. Doing a good job is a matter of honor.”

“The only thing I leave the world with is my word. A handshake is only as good as the one who shakes it. Paper can burn. Your word is the only thing that you take with you when you leave this world,” says Burris.

Rules & Regs

Most tribes believe the tribal first line of defense suffices because they have the most interest in making sure that everything is operated cleanly.

That’s also the view of Norman H. DesRosiers, vice chairman of the National Indian Gaming Commission, the federal agency that oversees Indian gaming. DesRosiers was himself a gaming commissioner for several tribes, and is credited with writing many of the gaming regulations that the great majority of tribal gaming commissioners use today.

“DesRosiers drafted phenomenal policies that are almost a standard for tribal gaming,” says Burris. “We all looked to Norm in the early days for guidance.”

DesRosiers started in 1993 as an inspector and training supervisor at Fort McDowell Tribal Gaming Commission. From 1994 to 1998 he was vice president of the Arizona Tribal Gaming Regulators Alliance and during that same period was executive director of the San Carlos Apache Tribal Gaming Commission. Later he served as commissioner for the Viejas Tribal Gaming Commission. He has been on the NIGC for two years.

He began writing the policies that so many tribes would use as a touchstone at San Carlos and finished them at Viejas.

“I did write a couple of tribal regulations that exceeded state and federal regulations,” says DesRosiers. “They were based on my experience with other tribal regulator agencies and things that could go wrong. I am proud and flattered that many tribes have used those models and even the state of California picked up on a few of those things.”

After about 14 years of tribal experience, “I got a pretty good feel for how to regulate it at all levels,” he says. The foremost insight he took away from that experience was that IGRA recognizes tribal regulators as primary. “In my experience most of those regulators are very protective of that sovereign authority,” he says.

“Any shared authority with the state is the product of government-to-government agreements, i.e. compacts. The federal government retains an oversight role in Class II regulation. We have to approve tribal gaming ordinances and management contracts and we have the right to review background investigations of key employees and the right to object to key employees,” says DesRosiers.

NIGC is certainly a busy agency, even if it doesn’t have direct responsibility for enforcing tribal gaming regulations. It has a field staff of auditors who perform compliance reviews, and another group that conducts background checks for management contracts. It reviews violations and ordinances to ensure that they comply with minimum requirements, or Minimum Internal Control Standards (MICS).

“Occasionally we provide opinions as to whether proposed gaming facilities are eligible. The chairman (Phil Hogen) and I spent a lot of time in the field consulting with tribes on proposed regulations.”

DesRosiers feels that once a tribal gaming agency establishes a record of meeting or exceeding federal regulations, that engenders confidence among state and federal regulators. “If they do that, they should get minimum oversight by those agencies. If I am a tribal commission and I do the job right I’m minimizing the number of visits from state and federal regulators.”

Burris contends that it ought to be obvious that a tribe will do a good job of regulating its casino since its own money is at stake.

Roberts agrees. “Some statements that come from the state contend that if tribes are regulating themselves that they must not be doing a very good job. We have tried telling the state and other agencies that the tribe is looking out for its own money. The purpose of this tribal commission is to protect the tribe’s assets. The tribe is going to employ as much proper rules and internal controls as it can. There are the minimum standards of NIGC, and there is the reality is that most tribes have more stringent rules. Valley View Casino has been open for eight years. We are constantly upgrading to take new technology into account. The tribe is looking out for its own money. Who else will do that?”

Another criticism that is leveled is that a tribal commission might show preference for a tribal member in a dispute.

“There are only 300 tribal members,” says Roberts, answering that charge. “How many of those actually go into the casino and play is very small. There hasn’t been an incident since I have been here where a tribal member was accused of something wrong. Employees who are members of the tribe are treated no different and no worse than other employees.”

Digging Deep

San Pasqual’s commission runs a very complex business. It is in charge of all audits. Every employee in the casino has to have a gaming license, which the commission issues after conducting background checks.

The state tribal gaming compact requires that certain “key” employees get a special license through the state. The tribe also runs key employees’ backgrounds checking for past criminal behavior. The commission uses a small machine that electronically scans fingerprints and sends them off to the FBI, which actually performs the checks.

Another vital function of most tribal gaming commissions is to monitor individual slot machines to make sure that they are working correctly.

At Viejas the commission has one commissioner with a staff of 59. Most commissions have administrative responsibility for their staffs. At Viejas, in addition to licensing staff members, they also license vendors, so background checks are necessary for them.

“It’s pretty extensive,” says Burris. “You are trying to determine suitability, from work history, credit to criminal past, if any. We are responsible for looking at people’s character and associations.” A former or current gang member, for example, would probably not be a suitable employee.

The compliance issues that a commission must address deal primarily with technology, says Burris.

“You inspect and test the electronic gaming units and the cards. We use national standards but we also use industry standards. As technology advances, the game is classified and you have a technical standard by which it functions. The statute always drives us. First it gives us our authority and then it gives us our direction.”

Standard Deductions

Where tribal commissions from tribe to tribe and state to state differ is in standards, although because of the efforts of DesRosiers and others those standards are becoming more standardized all over Indian Country.

“The unique thing about tribal gaming in California,” says Roberts, “is that we help each other. If a new tribe might not have the resources to put together regulations and standards we offer assistance to them for free. Because if one tribe stumbles-it reflects on all.

“Someone will call me up and say, ‘Shoot me your policies for table games.’ They may not have the resources to hire an accounting or law firm to draft those policies. Or we might go to their property and give them advice,” he says.

But increasingly, Roberts says, that standard of cooperation is extending across the entire Indian gaming map.

“Standards are similar statewide and nationally. They are at least equal to if not better than commercial regulations in Nevada or Mississippi. Their regulations do not surpass what we have in California.”

In DesRosiers’ mind there is no doubt that IGRA vests the tribes with the authority and the responsibility of regulating their own gaming operations. In many cases, state-tribal compacts also give tribes that responsibility.

“But much more important in my opinion, the tribal agencies are there, physically present 24/7, enforcing compliance, conducting investigations, settling disputes, conducting internal auditing and background investigations. They have a hands-on knowledge of their own facilities and at least at the federal level we depend on that front-line oversight and presence,” he says.

Typically, a tribal agency finds and investigates improprieties within days or even hours of the occurrence.

“If left to federal auditors it might be months or maybe forever and the evidence would be long gone,” says DesRosiers. “In my experience they are physically present to respond to protect the patrons’ interest when they are required to investigate disputes. It certainly helps in building the integrity of gaming operations to have gaming officials there to immediately attend to those issues.”

Burris agrees, “If we relied on the NIGC to oversee all of the facilities with a staff of 100 it would nowhere be adequate for our gaming facilities.”

Tribal Level

Federal statutes and regulations and IGRA establish the minimums, that tribes must have ordinances and minimum background and licensing requirements for key employees, plus requirements that tribes must safeguard the environment, public health and safety.

However, according to the commissioner, “through tribal ordinances and regulation and often as part of compacts, the tribes more often than not exceed those federal requirements. A lot of tribal regulations that I wrote had not previously existed and exceeded those models.”

Could the laws that created the relationship between tribal, state and federal gaming regulation be improved?

“If you ask a hundred different people you will get a hundred different opinions,” says DesRosiers. “Tribal people probably think it should be left entirely to them. If you talk to states they will tell you that laws should give them more authority in tribal affairs.

“From the federal perspective you will get a little different take. We think some things could be changed to clarify the issues. I think there is universal agreement that the act has made the best effort to try and balance the efforts of three sovereigns and not every sovereign got everything they wanted. But it has been enough to allow the industry to flourish and by most accounts to become one of the greatest economic successes for tribal governments that has come down the road.”

Class II: The Players

National Indian Gaming Commission

The NIGC has had nearly 20 years of experience in not making up its mind what constitutes a Class II game. Its initial instinct was to prohibit all electronic forms of bingo and pull tabs. After growing courtroom losses, it modified that position, through a series of advisory opinions (non-binding) and 2002 regulations defining what designs were permissible for Class II use as “technologic aids,” and what constituted a “facsimile,” which requires a compact. Even following promulgation of those 2002 rules, however, the NIGC continued to issue confusing advisory opinions (non-binding) and undertook its ill-fated “classification standards.” Under the guise of clarification, those standards attempted to redefine the statutory definition of “bingo,” eliminated “games similar to bingo,” and created an intricate structure apparently designed to render Class II games commercially non-viable. Tribal interests invested thousands of hours in opposing the proposal, which was ultimately withdrawn-and is, therefore, non-binding. The NIGC is due for some significant personnel changes. One commissioner position has been vacant for more than a year, and should be filled before too long. The chairman’s three-year term has now lasted more than six years, and he expects to leave as soon as a replacement can be nominated and confirmed. The direction and ambition of a reconstituted commission will bear watching.

States

States have neither the authority nor the expertise to determine whether a Class II game complies with the provision of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. Most such efforts focus on a game’s appearance, and on whether, from an outside perspective, it looks, plays and feels like a Class III game. Some years ago, when the United States Department of Justice proposed a similar test-that IGRA did not permit games that were “too fast, fun and lucrative”-even the NIGC fought back. In recent months, some states have attempted to apply the provisions of the NIGC’s withdrawn criteria for Class II games. But those criteria never made it to law, and if the NIGC cannot enforce those standards, even less can the states do so. Further, the states have no right to enforce any standards. When Congress enacted the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, it did not do so in a vacuum. The Supreme Court had acknowledged tribes’ inherent regulatory authority over bingo operations on their tribal lands, exclusive of state regulation. In the IGRA, Congress took away some of that exclusivity as to a gaming category it called Class III. To operate Class III games, therefore, a tribe must reach agreement with a state over Class III regulatory provisions or, when an agreement cannot be reached, enter the labyrinthine process of litigation and administrative challenges. But Congress did not abrogate any measure of tribal exclusive regulation of Class II games, and provided an oversight role only to the NIGC. State power over Indian gaming is limited to Class III. Since the United States Supreme Court invalidated tribes’ ability to enforce good faith compacting (Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida), states can stonewall compact negotiations, or impose unfair compact demands without judicial retribution. Their power is substantial, but it is limited to Class III.

Tribes

Tribes have always been the primary regulators of Class II gaming. Tribal gaming regulatory agencies staff the front lines in assuring the integrity and fairness of the tribal facility, and in that role, have learned much about the functioning of Class II games. Class II technologic aids were developed entirely in response to tribal needs to enhance Class II gaming. In general, such gaming systems were needed in jurisdictions that refused to enter into compacts to permit tribal Class III gaming. Tribal regulatory agencies developed and implemented rules necessary to protect the interests of both the tribe and the gaming public. The first, because the purpose of the IGRA is to provide for tribal economic development. The second, because the public will not long return to a crooked facility. Over the years, Class II gaming has matured at much the same rate as technology in other comparable areas. Tribal gaming regulators have reviewed and evaluated each new game, and have dealt with the inevitable bugs and fixes. That expertise was manifest in the advice provided to the NIGC in connection with the MICS and technical standards proposals. That same expertise can be utilized to provide a better foundation for understanding the proper classification of technological aids to Class II games.

IGRA’s Impact

n October 16-17, 2008, the Arizona State University School of Law hosted a conference at Fort McDowell Casino to commemorate and critically examine the 20 years of Indian gaming under the 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. The event attracted scholars, policy makers and tribal representatives from around the country, many of whom had participated directly in the creation and implementation of the act. Our paper examined the economic impacts of Indian gaming under IGRA and complemented the political work presented by other academics whose work examined the ways that IGRA resolved specific legal and regulatory dilemmas and allowed tribes to pursue Class III gaming without fear of federal criminal prosecution. An excerpt from the paper appears here:

The Growth of Indian Gaming

In recent years the NIGC has regularly released tables and charts reporting the gross gaming revenues of Indian casinos-that is, the total revenues net of prizes paid for every Indian bingo hall and casino across the country. Predictably when these data are released, commentators note the burgeoning Indian sector of America’s growing gambling industry.

Upon the release of the latest gaming revenue figures, which reached $26 billion in 2007, the commission chairman, Philip N. Hogen, noted, “The continued growth [of Indian gaming revenue] is significant considering recent economic struggles throughout the country. The Indian gaming industry has experienced tremendous growth since the inception of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act 20 years ago in 1988.”

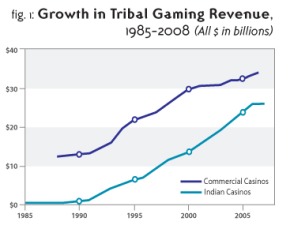

The numbers warrant Hogen’s accolades of “significant” and “tremendous” (Chart 1). In inflation-adjusted terms, Indian gaming exploded more than a hundred-fold from $171 million in 1985 to $26 billion in 2007, for an average compound growth rate of 26 percent per year after inflation. As the light blue line in Chart 1 indicates, Indian gaming grew rapidly in comparison with the commercial casino sector as well, jumping from 2 percent of its size in 1988 to more than three quarters in 2007. Back in the opening days of bingo halls at Penobscot, Seminole, Shakopee and elsewhere, few observers had any inkling that such growth was in store for Indian Country. Yet while the growth of Indian gaming appropriately deserves its many superlatives, growth has not been uniform over time. (See fig. 1.)

To the human eye, the growth of Indian gaming revenue in the chart appears simply “exponential.” That it is, but there is more than meets the eye: the exponential growth is not consistently so. When the same data is portrayed on a log scale, wherein the intervals between grid lines change from constant increments in the chart to constant proportions, it becomes clear that the pace of Indian gaming growth had three major phases. On the log scale, steady rates of compound growth in Indian gaming revenue appear as straight lines, and there are three roughly straight-line periods in the graph. Up until 1988, compound annual revenue growth was modest-in the single digits. For the five years beginning in 1988, growth leapt to an average of 79 percent per year (light blue line in the chart). And beginning in 1993, growth cooled substantially to a steady 15 percent per year over the 1993-2007 period. Virtually no growth took place in the last of those years: growth was 0.4 percent after inflation. (See fig. 2.)

In fig. 2, the log scale shows steady compound growth rates as straight lines.

Abrupt corners in a graph like fig. 2 beg further examination. That Indian gaming grew quickly in the five years after IGRA probably does not strike knowledgeable participants from that time as news, but the period when that growth took place is striking in retrospect. The Supreme Court decided Cabazon in 1987, and IGRA became law in 1988. The coincidental uptick in growth points to the power of these actions to unleash capital flows-of both financial and human capital-to Indian Country. Clearly, Cabazon certified to the outside world the civil and regulatory freedoms tribes had been asserting, but did IGRA help too?

Legal and political observers, most importantly tribal leaders and representatives, often (and correctly) note that IGRA constrained American Indian powers of self-determination in gaming relative to what Cabazon afforded. But in a very real sense IGRA also lifted from Indian gaming the heavy burdens of political and regulatory uncertainty.

Of course, the effect was neither complete nor uniform. Gubernatorial recalcitrance held down investment in California for more than a decade after IGRA’s passage. “Friendly” and unfriendly lawsuits in Washington, New Mexico and elsewhere were necessary to settle the nature of compacting authority, game types, revenue sharing, and a host of other issues relevant to the Indian gaming investment climate. The Seminole decision, of course, vitiated a central congressional assumption in the compacting framework. Notwithstanding its shortcomings, however, IGRA went far in organizing the process by which state and tribal claims could be resolved.

Thus to the tribal leader’s correct observation that IGRA constrained Indian nations, the economist raises his familiar question: Compared to what? Wouldn’t Indian gaming revenue have continued at a slow pace of growth under a Cabazon-only rubric as it had done under a Butterworth-only framework?

Recall that state governors and members of Congress were up in arms about regulation and competition against non-Indian casinos. For how long would tribal governments have suffered slow gaming growth, and at what loss of net present value for tribes? Any delay in the arrival of the steep upward slope indicated by the light blue line in fig. 2 would carry consequences in the tens of billions of dollars for Indian Country.

It may forever be impossible to disentangle IGRA’s various abetting and hindering influences from Cabazon‘s broad acknowledgment of tribal regulatory authority because the two come so close together in time, but the acceleration in growth visible in fig. 2 raises the bar for those who lament the state compacting provisions in IGRA.

Yes, IGRA constrained the tribal sovereignty that is so essential to American Indian economic development. Yes, IGRA’s shortcomings as a framework for accommodating tribal and state interests effectively and efficiently are plainly evident.

On the other hand, is not five consecutive years’ worth of 79 percent compound annual growth a necessary proof that IGRA made investors-and tribes themselves-feel much more secure about directing resources toward Indian gaming development? How intensely were electronic gaming machine companies investing in Class II technologies before IGRA? How cheap and accessible was the capital necessary to create a Foxwoods, a Mystic Lake, or an Emerald Queen prior to IGRA, if at all? How readily were state governments cooperating to build highway off-ramps to Indian reservations? Good institutions of government make investors feel secure by reducing political, legal, and regulatory uncertainty, and IGRA, flawed as it was, created an environment that clarified tribes’ role in the federalist matrix of government-to-government relations in a way that was more than just good enough to get that job done. Would Cabazon alone have done as much? If so, when?

The second “corner” of fig. 2 comes in 1993 and presents puzzles in itself and perhaps even challenges the above explanation for the significant uptick in 1988. If IGRA created beneficial investment conditions in 1988, did something make them less attractive after 1993? If so, what? That year brought with it a new administration, and it is conceivable that BIA procedural changes introduced delays or uncertainties. A more plausible scenario is that in May 1994-the year growth fell substantially-Connecticut and Mohegan signed their gaming compact, which among other things extended Mashantucket Pequot’s 25 percent revenue-sharing terms to a second tribe. Perhaps that compact introduced higher stakes into compact negotiations around the country, thereby introducing uncertainty.

On the other hand, that compact extended statewide exclusivity to Mohegan, which would tend to accommodate growth in investment. It may also be the case that the uptick in 1988 was an accounting anomaly because revenues prior to IGRA were not centrally monitored as closely as they were after IGRA’s passage.

This explanation may be weakest because an improvement in the accuracy of reporting would probably not begin and end abruptly over five years. Whatever their underlying causes, the discontinuities in the revenue trend in Chart 2 are remarkable in their own right, and an invitation to more investigation.

The ASU conference looked retrospectively at 20 years of Indian gaming under the frameworks of IGRA, describing jurisdictional conflict, legal and regulatory unpredictability, and political change. As tribes and states look to the future, the global recession and financial market collapse compound the uncertainties.

Nonetheless, the story of economic growth achieved under a framework that settled the place of tribes in the federal system-at least for a few issues and a few years-holds out the promise that Indian gaming can grow rapidly again under conditions that the tribes and the federal government themselves have the power to create. With luck, the states will recognize their enlightened self-interest in supporting such growth as well.

Trust and Responsibility

Tribal fee-to-trust issues will be defined in the next year by how tribes respond to challenges both fundamental and mundane. The Supreme Court decision in Carcieri v. Salazar will take center stage until the matter is resolved or trumped. Other recent and lingering matters hinder or facilitate tribes seeking trust acquisition, including the recently issued Opinion of the Solicitor regarding restricted fee lands and gaming, the viability of the January 3, 2008 guidance memorandum, Bureau of Indian Affairs elimination of trust acquisition performance standards, and potential fee-to-trust regulations.

Seminal Supreme Court Case

The Supreme Court issued its opinion in Carcieri v. Salazar on February 24. By press time, the Senate and House may have held hearings on the matter, and perhaps a fix will be in development.

The Supreme Court held the wording of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 (IRA) limited the secretary of the interior’s trust acquisition authority to tribes that were under federal jurisdiction as of the act’s enactment.

The court substantiated this holding through a strict interpretation of the act’s use of “now under federal jurisdiction” and the legislative intent to stem the loss of land sustained by tribes under the General Allotment Act. The court concluded section 2202 of the Indian Land Consolidation Act ensured tribes that were under federal jurisdiction in 1934, but opted out of the IRA, could still benefit from the trust acquisition provisions of the IRA.

The majority opinion, concurring opinions and dissenting opinions offer no clear application of this holding. Yet to be determined is the meaning of “under federal jurisdiction.” Carcieri will spawn additional questions if a congressional fix is not imminent. For example, Justice Stephen Breyer noted in his concurring opinion that the Department of the Interior, concurrent with the passage of the IRA, compiled a list of tribes it believed were subject to the IRA. None of the justices concede the list is conclusive evidence the federal government exercised jurisdiction with respect to only those tribes. In fact, Justice Breyer noted the department wrongly omitted tribes from the list. He asserted further that specific historical instances illustrate a pre-1934 jurisdiction over a tribe even though the recognition occurred after 1934. Justice Breyer listed three factors that may indicate a tribe was under federal jurisdiction in 1934: 1) a treaty with the United States still in effect in 1934, 2) a pre-1934 congressional appropriation, or 3) enrollment with the Indian Office in or before 1934.

The court’s lack of guidance will impact the trust acquisition process for some tribes until the Department of the Interior and Department of Justice weigh the ramifications of Carcieri and determine the proper administrative responses, or the federal courts build upon this holding in forthcoming cases. Congress may fill the void with a legislative fix. As noted, the Senate and House will hold hearings in the beginning of April. While this issue will be a critical matter for all tribal leaders, this will surely be a topic of great interest for cities, counties and states, as well as opponents of tribal sovereignty. Tribal leaders must carefully assess the goals and strategies associated with a potential legislative fix.

Solicitor’s Opinion

The Solicitor of the Department of the Interior concluded, in a January 18 M-Opinion, that section 2719 of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act does not apply to land held in restricted fee. From 2002 until the issuance of this opinion the department applied the section 2719 prohibitions to lands held in restricted fee to foreclose a perceived loophole that might allow tribes to game on land acquired after IGRA’s enactment date. Secretary Gale Norton sought to prevent this circumvention of IGRA. She reasoned Congress intended not to limit the restriction to only per se trust acquisitions, but to all after-acquired land, including restricted fee land. The January 18 solicitor’s opinion limited this expansive interpretation by applying section 2719 to lands that were taken into trust pursuant to the IRA.

The solicitor stated that Secretary Norton’s concerns about a loophole were based on an assumption that off-reservation lands acquired by tribes after IGRA’s enactment would be subject to an automatic restriction on alienation imposed by the Non-Intercourse Act. The department has since determined this act applies only to “Indian Country” and lands outside of the reservation do not automatically qualify as Indian Country. On January 20, the National Indian Gaming Commission followed this rationale when it released its opinion on the Seneca Nation’s Class II gaming ordinance. It reiterated IGRA section 2719 cannot apply to land held in restricted fee and the Non-Intercourse Act does not apply to off-reservation fee land.

The solicitor and NIGC opinions have little impact on the off-reservation gaming issue, especially after City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation, which stated that the IRA provides the process for a tribe to reestablish sovereignty over land. However, its import may be in the unequivocal statement that the Non-Intercourse Act’s restrictions against alienation do not automatically attach to off-reservation parcels acquired by a tribe in fee simple absolute. Certain tribes have been forced by title companies to seek an approval from Congress prior to selling off-reservation fee land. These opinions should end this arduous and unnecessary step.

Land-Into-Trust for Gaming

On January 3, 2008, the Department of the Interior issued its memorandum entitled “Guidance on Taking Off-Reservation Land into Trust for Gaming Purposes.” The memorandum elaborated on departmental considerations when weighing the mandates of 25 C.F.R. section 151.11(b). This regulation mandates that the secretary, when contemplating an off-reservation acquisition, “shall give greater scrutiny to the tribe’s justification of anticipated benefits from the acquisition” as the distance between the proposed land acquisition and reservation increases.

The memorandum directed the reviewers to scrutinize two economic benefits to tribes: the income stream from a casino and the job training/employment benefits. It stated that “no application to take land into trust beyond a commutable distance from the reservation should be granted” unless the application analyzes and demonstrates how the negative impacts on the reservation are outweighed by the financial benefits of the gaming facility.

The new administration will soon have the opportunity to weigh in on this issue. The St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin challenged, in April 2008, the validity of this memorandum and other actions taken by the department regarding its off-reservation gaming application. Since that time, the Tribe lost its challenge in the district court and its off-reservation fee-to-trust application was denied.

However, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia recently denied the U.S. government’s motion to dismiss and ordered the federal government to file a brief in response to the issues raised in the tribe’s appeal. In short, the Department of the Interior will be forced to either defend issuance of the guidance memorandum or to withdraw it and review these issues again.

No matter the outcome of this case, any tribe seeking to establish an off-reservation gaming operation still must meet the mandates of the 25 C.F.R. section 151.11. Tribes should develop applications that preemptively and conclusively address the greater scrutiny standard of the regulations.

Elimination of Trust Performance Standards

While more mundane than Supreme Court decisions and solicitor opinions, the BIA director’s elimination of performance standards for regional directors related to acquisition of tribal land into trust will have a profound impact on tribal attempts to take land, both on and off reservation, into trust. In fiscal year 2008, the BIA director inserted into the performance standards of the regional directors goals for the acquisition of land into trust in each region. This prioritized the review and determination of fee-to-trust applications by the regional offices over other tasks within these offices. This yielded determinations on hundreds of applications and the acquisition into trust of over 50,000 acres through the 25 C.F.R. section 151 process in one year.

The subordination of the land into trust issue by the BIA central office signals that tribal applications for land into trust will be forced to compete for time and money with other important programs.

These other programs may not yield the same impact on sovereignty and jurisdiction for the tribes. If tribal leaders want to re-establish this as a priority within their regions, they must emphasize the importance of this issue with the incoming assistant secretary of Indian affairs and the director of the BIA. Performance standards development begins in April of every year and culminates in early September.

Amendment of the Fee-to-Trust Regulations

A perennial fee-to-trust issue is the deliberation and promulgation of new fee-to-trust regulations. This will be on the horizon for consideration again. I think a few issues will influence this rulemaking process. First, tribal leaders will gauge the impact of the Carcieri case and its potential subsequent legislative fix. The legislative consideration of this matter may prove to be a coalescing event and training ground for all conceivable stakeholders in the fee-to-trust process, from disparate tribal opinions to regional interests to express opponents of tribal sovereignty and jurisdiction. Depending on the outcome of the legislative process, tribal leaders may urge the department to postpone reconsideration of the regulations, especially if the administrative process expands the initial consultation process beyond tribal concerns.

Second, the recently issued fee-to-trust handbook may forestall reconsideration. This handbook promulgates homogeneous fee-to-trust process throughout the nation. The BIA will hold its first tribal leaders dialogue meeting on the handbook in April. The current version purposefully omits off-reservation discretionary trust acquisitions and mandatory trust acquisitions sections. This will allow tribal leaders to participate in the development of these sections and refinement of the on-reservation acquisition portion.

Even if the fee-to-trust regulations are not considered this year, determining the impact of the Carcieri case, anticipating the outcome of the St. Croix challenge to the January 3 Guidance Memorandum, and working with the BIA to continue its laudable prior performance regarding the fee-to-trust matters should prove to be a full-time job for all those interested in the trust acquisition process, both on and off reservation.

Betrayal of Trust

It has long been the belief of this nation’s first Americans that the federal government would attempt to rid itself of its trust obligations to American Indians. That prophecy is becoming realized in recent federal court decisions and congressional attempts to erode tribal sovereignty and the inherent right of first Americans to govern their people, on their lands.

The trend was accelerated dramatically last month with the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Carcieri v. Salazar. The ruling is creating great uncertainty for a number of Indian tribes seeking nothing more than the ability to exercise their governmental right and authority to provide for the welfare of their people.

Justices in Carcieri v. Salazar ruled that Indian tribes not recognized or under federal jurisdiction when the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) was passed in 1934 were barred from using the act’s land-into-trust process to establish a homeland.

U.S. Senator Jack Reed (D-Rhode Island) was correct when he suggested casino gambling was “lurking behind” the greater and far more important issue: the trust relationship between two sovereigns, American Indian tribes and the federal government.

The Supreme Court, ruling on efforts by the Narragansett Tribe to place 31 acres of land in trust for a casino, prevents numerous other tribes recognized after 1934 from obtaining economic self-sufficiency through tribal government gaming by blocking their ability to place land into trust for casinos.

Interior Secretary Ken Salazar quickly released a statement saying he was disappointed in the decision, which ignores long-held practices by the department in placing land in trust for tribes.

“The department,” he said, “is committed to supporting the ability of all federally recognized tribes to have lands acquired in trust.”

House Natural Resources Committee Chairman Rep. Nick Rahall (D-West Virginia) said the ruling “could throw a shroud over the sovereign nature of land held by untold numbers of Indian tribes.” He pledged to conduct a hearing on the matter.

It is incumbent on the U.S. Congress to remedy the situation.

Indian Gaming Brings Benefits

It is time Congress, the courts and others cease using gaming as an excuse to erode tribal sovereignty and self-governance and rid itself of the federal government’s trust responsibility to the first Americans.

Tribal government gaming has proven to be a successful and productive economic development tool for Indian Country. Gaming is creating jobs with competitive pay and benefits for Indians and non-Indians. It is providing tribes with the resources to fund critical public services on reservations.

Non-Indian businesses near tribal reservations have seen their operations grow as a result of patronage by tribal governments.

Indian gaming has made it possible for young Native men and women to pursue their education at universities, colleges and vocational schools. It is helping tribes revive their languages and preserve their culture.

Communities surrounding tribal reservations have benefited from the vision and generosity of tribal governments.

The San Manuel Band of Mission Indians near San Bernardino, California, recently awarded more than $7.3 million to charitable organizations and community groups in Southern California and the western United States, enabling these groups and organizations to continue their good work and outreach. In the current economic environment, many more Americans are relying on these organizations for their basic needs.

Indian gaming is enabling tribal governments to become significant contributors to community improvements on and off their reservations.

The Supreme Court ruling threatens these opportunities for a number of tribal governments and their neighboring communities.

Congressional Action is Needed

Congress must act now to restore the right of all tribes to take lands into trust.

Elected officials on Capitol Hill must realize that some 90 million acres of Indian lands were lost from 1887-when a federal police of allotting tribal lands was imposed-and passage of the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934. Only 5 million acres have since been reacquired and placed in trust for Indian tribes.

Congress was quick to embrace the stimulus package offered by President Obama, passing the legislation in record time. It acted quickly to enact financial recovery programs for auto makers and financial institutions.

Indian tribes deserve the same speedy consideration.

Indian Country was optimistic when President Barack Obama took the oath of office. He and his administration have a real-time opportunity to honor the treaties and promises made to Native nations, a pledge he made to Indian audiences during his campaign. The president should confer with Congress and encourage them to quickly develop a fix.

It is difficult to gauge just how far-reaching Carcieri v. Salazar may prove to be. But without congressional action, options are limited and the future is bleak for a number of tribes.

There is reason to be hopeful. Native lawyers and policy analysts are reviewing the decision. Soon they will offer their guidance on the best course for Indian Country.

This also was predicted by tribal elders.

When Down Looks Like Up

In these difficult and unprecedented times, few industries or businesses have proven themselves immune to the effects of recessionary activity. All parties in the “economic food chain” are experiencing pressure, and even those outperforming their competitors are reassessing their approach and positioning.

This is particularly true in many corners of Indian Country, where reduced cash flows at gaming properties are beginning to influence the financial position, both inside and outside of the casino walls. And when the economic engine of gaming starts to show significant declines in profitability, the community programs those dollars support may also be in jeopardy. Tribes recognize that the right response is needed. And quick.

If there is a silver lining, it just may be that because the current environment is so incredibly challenging, it is forcing tribes throughout the U.S. to closely evaluate (if not completely revisit) their business, marketing and construction/development plans-and “operational soul searching” of this intensity has a way of yielding some unexpected benefits. For the tribes who do it right, the changes they make now should not only help their tribal properties weather the current crisis, but will also result in more streamlined operations and effective business models that should help bolster profits for years to come.

Perspective

The gaming industry continues to be adversely affected by the economic downturn. In order to offer some perspective, let us look at the performance of the major gaming industry indices. As of March 6, the Dow Jones U.S. Gambling Index is down 18.2 percent for the year (following a decline of 73.3 percent in 2008). Relative to a 7 percent decrease in the S&P 500 over the same period, the data tells us that gaming is no longer a preferred sector for investors. Furthermore, shareholders in the world’s largest gaming operators-Las Vegas Sands, MGM Mirage and Wynn Resorts-have lost more than $70 billion of market value since the beginning of 2008.

From a credit perspective, the data is not any better. Within Fitch’s U.S. High Yield Default Index, the gaming sector experienced a record default rate of 32 percent in 2008, well above the overall high-yield market default rate of 8.5 percent. Seven issuers defaulted on more than $13 billion of high-yield principal. Twenty-one companies received credit rating downgrades from Moody’s, nine of which were Native American operators. To date in 2009, three Native American entities have been downgraded including Mohegan Tribal Gaming Authority, Mashantucket Western Pequot Tribe and Snoqualmie Entertainment Authority. Fortunately, the news is not all bad. While destination markets like Las Vegas and Atlantic City continue to generate record decreases in revenues, many regional gaming markets are benefiting from a lack of travel by gamers. For example, Mississippi and Louisiana have shown small decreases or even small gains as they have rebuilt after Hurricane Katrina’s devastation. Many new properties in these regions have improved their competitive position in comparison to their predecessors. Beyond commercial gaming, a handful of Native American properties in regional markets have improved their competitive positioning, notably the Seminole Tribe of Florida.

Impact on Tribal Enterprises

While much of this data may make many investors and operators nervous, it offers an opportunity for an in-depth review of the casino operations as well as the capital structure. With a solid framework in place, entities can preserve one of the most important aspects of business for many Native American operators: tribal distributions.

Cash flows provided by tribal gaming enterprises are of the utmost importance to tribal governments and act as lifelines for the majority of Native American tribes. Not only do these distributions fund tribal programs such as health care, education and infrastructure, but individual per capita payments also augment incomes for many tribal members.

Unlike a traditional corporate structure, Native American tribes operate in an interrelated environment whereby the casino operations cannot exist without tribal government, yet the tribal government is dependent upon the funds provided by the casino. Given this dynamic, the interests of the tribe and creditors are aligned. Both parties stand to benefit when the tribe operates the casino in a way that maximizes cash flow generation and profitability.

Commercial Mindset

Looking forward, it is our expectation that most, if not all, tribal entities will act commercially to preserve value for all of their stakeholders, including tribal members and creditors.

Even with limited refinancing options available due to the credit crisis, many tribes understand that they will need to tap the commercial credit markets at some point in the future to refinance their balance sheets and fund expansions or new projects. Additionally, tribes must recognize the potential impact on future generations from the decisions made in today’s difficult environment.

Give and Take on Both Sides

As noted earlier, the interests of tribes and creditors are often aligned. Both parties will need to approach discussions regarding tribal distributions in good faith, but may need to make concessions. Many debt agreements for Native American gaming enterprises permit guaranteed minimum distributions to fund essential governmental functions, even in the event of a default.

If during this difficult economic time, however, a situation arises where the gaming entity cannot make required interest payments, tribes may be forced to cut back on non-essential programs similar to state governments experiencing major budget deficits.

Ultimately, creditors need to permit distributions at a level where tribes can continue running their governments, otherwise, the tribe may have no reason to continue operating the very business that is expected to pay back its loans. Difficult decisions will need to be made, but they are necessary to align distribution expectations with the current economic environment.

How Are Tribes Responding?

Native American operators are responding by focusing on things they can control-announcing deep cost-cutting measures, reducing staff and delaying major development projects.

For example, Mohegan Tribal Gaming Authority announced in January a number of initiatives including reductions in salaries for senior executives, suspension of compensation increases, 401(k) contributions, and a reduction of hours of operation for some businesses. In September, the Mohegan Tribe also announced the delay of its $925 million expansion plan.

Long Overdue?

An interesting irony has emerged for tribal operators with regard to staffing levels. When tribes are positioning themselves for the development of a casino, the promise of job creation can be crucial to gaining political support and the approval of a state compact. Some even over-hired to prove their benefit to the local economy, creating inefficiencies and excessive payroll costs.

Although layoffs and downsizing are not welcome for anyone now, the current situation has forced tribes to deal with this issue and find a way to finally right-size their staffing levels. While it certainly is not the preferred method of addressing such a situation, tribal casinos are like every other business and have taken necessary measures to reduce such overhead costs and improve their profitability. Unwelcome, maybe. Overdue, definitely. These decisions may not be the best political moves both locally and within the tribal membership; however, these challenging times are requiring unpopular decisions.

Another positive development has surfaced out of the recession in the form of improved marketing programs. Whereas tribal operators may have had little need for highly targeted and perceptive marketing during the high-volume days of the recent past, creative and patron-sensitive tactics are now necessary for survival. Between reductions in staffing and enhanced marketing, tribal operators can improve operations and position themselves for a future recovery.

The Government Weighs In

The federal government is doing its part to assist tribes in their economic development. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 provides Native American tribes the authority to access up to $2 billion of tax-exempt bond funding to finance hotels and other non-gaming amenities using tax-exempt bonds.

In addition, the National Indian Gaming Commission recently issued a letter regarding the securitization of financings by a pledge of gross gaming revenues. The NIGC had questioned the validity of such financings, expressing concern that the documentation for such financing is void unless it has been approved by the NIGC chairman as a gaming management agreement. The letter did not object to securitization by gross gaming revenues and set forth a specific list of restricted creditor actions. Creditors are not permitted to engage in any “management activities” including supervision of personnel, determination of hours of operation, marketing, accounting, operation or purchase of gaming machines and allocation of operating expenses. By offering clarity on this issue, tribes and creditors now have a detailed operational guideline in the event that gaming revenues do not meet expectations. In summary, the NIGC has stepped forward with additional guidance that will be beneficial to both tribes and creditors in the future.

Time Will Tell

Despite the negativity and difficult economic environment, there is a silver lining for tribal gaming operators. The rationalization and right-sizing of cost structures will result in more efficient businesses and solid foundations for long-term success and profitability. A proactive mindset and foresight is crucial to weathering the storm and emerging unfazed.

The best operators are making informed decisions assisted by their financial and legal advisors. While no one truly knows how long the current recession will last, these businesses will be well-positioned to take advantage of more prosperous times.

Together Forever

As Indian Country confronts the economic crisis, it is empowering to see the strength of tribal governments as they tackle issues ranging from the threat of increased federal regulation to meeting the basic needs of their communities. It has been through the hard work and the dedication of the tribal leaders throughout Indian Country that Indian gaming will be poised to lead us out of this economic crisis with a renewed sense of optimism.

In just 20 years, Indian gaming has grown into a stable, professional and responsible industry that generates vital resources and jobs that were not previously available. This is attributable solely to the hard work and innovation of our tribal governments. It should never be forgotten that when Congress passed IGRA it was at the urging of the states that wanted to reduce tribal sovereignty. Despite IGRA, tribal governments succeeded and fostered an industry with over $26 billion in revenue and accountable for over 700,000 jobs nationwide. Now more than ever, tribal governments need to call on their resourcefulness and innovativeness once more to tackle and weather this current economic crisis. In addition, Indian Country must continue to come together and foster change for all and develop effective partnerships that will deliver federal policies in the spirit of tribal sovereignty and tribal self-governance, along with a renewed regulatory outlook.

Tribal Governments and the New Administration-Forging a New Path Forward

A new congressional leadership has taken office and President Obama has begun aggressively pursuing his agenda. From the beginning, President Barack Obama has expressed his commitment to deal with tribes on a government-to-government basis. Tribal governments should now put the president’s words into action.

Indian Country is calling upon President Obama to issue a new executive order requiring federal agencies to consult with tribal governments on all regulations that impact tribal operations. The last executive order on tribal consultation was issued by President Clinton in 2000 and is in desperate need of updating. Thanks to the growth tribes experienced in the last nine years, tribal operations can now be impacted by federal regulations that were never even intended to apply to tribes. These types of regulatory intrusions can be solved through government-to-government consultation with tribal leadership. Some of Indian Country’s biggest challenges have been from government agencies and their lack of effort to consult with tribal governments and meet with tribal leaders in a meaningful and respectful manner.

I am confident that President Obama was sincere in his campaign pledges to Indian Country and that this will translate into a federal policy that all government agencies are required to enact. However, we need tribal governments to contact not only the White House, but also their congressional representatives and let them know that Indian Country is awaiting this important policy initiative.

At NIGA, we helped push for the introduction of House Bill 5608, which will statutorily require federal agencies to consult with tribal governments. This legislation is necessary because unfortunately, we have seen federal agencies intent on regulating a problem into existence, rather than evaluating if there was a problem at all.

I believe that NIGA, along with the National Congress of American Indians, National Indian Education Association, National Indian Health Board and other Indian organizations, can capitalize on achieving a respectful dialogue with the federal government. A lot of our challenges over the next four years will be something we can work to solve, as opposed to battling with a federal agency to prevent an unwarranted solution.

The Current Federal Regulatory Environment

Forging a new regulatory partnership between tribes and the federal government is certainly needed after the National Indian Gaming Commission had one of its busiest regulatory agendas in recent years. In 2008 alone, the NIGC sought to finalize four new Class II gaming regulations that would have negatively impacted Indian Country. They also proposed to redefine the definition of “sole proprietary interest” under IGRA, and finally, they passed regulations requiring tribes to submit paperwork on the trust status of their own lands.

In 2009, we can expect the NIGC to again address several issues important to Indian Country. However, Indian Country wants to see a new NIGC chairman at the helm who will implement the tribal consultation policies initiated by the president. We thank Chairman Phil Hogen for his service, but his original three-year term expired in December 2005. The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act allows for the commissioner to serve past his three-year term until a successor has been named, which we have asked President Obama to do this year.

The important position of general counsel at the NIGC has also remained unfilled for a number of years. Indian Country and the Indian gaming community will call upon the Obama administration to fill that position as well. Indian Country must demand an NIGC that is a partner in regulation. We hope that the Congress will appoint associate commissioners who share Indian Country’s desire to negotiate on regulatory initiatives and mandated from above.

Class II Regulations

Last year, with the assistance of our member tribes and regional gaming associations, NIGA coordinated an effort to oppose the NIGC’s overreaching Class II definition and Class II classification regulatory proposals. The NIGC’s new regulations would have overturned hard-fought federal court victories by Indian Country in defense of Class II gaming.

In a big victory for Indian Country, the NIGC officially withdrew those regulations in October. The NIGC officially withdrew their proposed Class II classification standards and changes to the definition of “electronic or electromechanical facsimile.” NIGA and Indian Country had long voiced their opposition to these two proposed regulations. Indian Country’s opposition only increased when the NIGC released an economic impact report detailing the dire economic consequences for Indian Country if these regulations became law.

By convincing the NIGC to withdraw the classification and definition regulations Indian Country achieved a great victory in defending the Class II industry. Our congratulations go out to all those tribal leaders who helped fight these regulations over the past two years.

However, the NIGC still went ahead and published Class II Technical Standards and MICS. We have asked that the Obama administration, along with the new NIGC chairman, bring these issues back to Indian Country for further consultation.

Tribes continue to be unhappy with the Class II Technical Standards and MICS. The game-recall provisions of the proposed technical standards require the player interface to display results of any alternate display. This requirement confuses the reality of the game and may obscure the distinction between the legal relevance of a bingo game and any alternate entertaining display. More consultation with tribal governments is needed to resolve these outstanding issues. Only then would these regulations be ready for final publication.

Last-Minute Regulatory Changes By The NIGC

On December 22 the National Indian Gaming Commission published in the Federal Register proposed rule changes. The proposed rule seeks to modify “various commission regulations to reduce reporting burdens on tribes, update costs for background investigations, clarify definitions and regulatory intent, and update audit requirements to consolidate and reflect industry standards.” Many of these proposed rule changes were initially released as drafts by the NIGC in 2006. These rule changes have not been priority for the NIGC and the NIGC has not engaged in dialogue with tribal governments since their initial debut.

President Bush’s OMB director directed federal agencies to stop issuing agency regulations on November 1. President Obama’s chief of staff directed agencies to stop issuing regulations unless an Obama appointee had reviewed them on January 20. The NIGC failed to follow either of these presidential directives and Indian Country must demand that the NIGC withdraw the proposed rule changes.

While some of the proposed changes are minor, tribes have strongly objected to the proposed rule changes to the statutory definition of “net revenue.” Any NIGC regulation on this definition should conform to the statutory definition under IGRA. By striking the word “gaming” from the definition, the NIGC is seeking to include non-gaming revenue in the calculation of net revenues, such as hospitality revenue generated at a casino-resort complex. This would clearly not be consistent with IGRA. Instead, the NIGC should stay closer to the statutory language mandated by Congress in IGRA: “The term ‘net revenues’ means gross revenue of an Indian gaming activity less amounts paid out as, or paid for, prizes and total operating expenses, excluding management fees.”

There should be courtesy between the outgoing and incoming presidential administrations. The responsibility of amending existing federal regulations belongs to the incoming commission that will be appointed by President Obama and BIA Secretary Ken Salazar. This is why it is important that Indian Country deliver the message to President Obama that the NIGC should not finalize any rules until a new chairman and a new associate commissioner are appointed.

Consultation

Last year’s NIGC activity highlights the fact that there must be a new partnership between tribes and the federal government in implementing and carrying out federal regulations. Indian Country must seek a consultation process where tribal representatives are active participants from the beginning in deciding whether federal regulation is needed or if tribal law processes are the more responsive avenues for effective regulation. Indian tribes must have a more active role not only in providing advice and input, but also in the drafting process itself.

President Obama has promised at least this much and tribes must begin this process with his administration. We feel that tribal governments, as the first-line defenders of Indian gaming, have a strong track record of experienced professionals and top-notch regulation. In 2008 alone, tribal governments spent over $375 million on regulation. Tribes realize that the benefits of Indian gaming would not be possible without good regulation. Successful operations require solid regulation and tribal governments will match their history of regulation against that of any state or local government.

This system is costly, it’s comprehensive, and it has a proven track record of success. We need the Obama administration to work with and consult tribal governments so that we may improve upon the success of regulatory systems and the current state of tribal-federal relations.

In 2009, we again expect to spend a great deal of our time and effort defending the success of our industry from unnecessary regulatory interference. However, given the economic stake that states and local communities and business leaders now have in the success of Indian gaming, I see a new opportunity for regulatory cooperation. Our tribal leaders are open to consultation and the development of new regulations when they are needed.