At some point, a lightbulb lit up and someone cried out, “Casinos!” A bit over simplistic, perhaps, but in retrospect, it was a stroke of genius for Native Americans despite legal roadblocks that had to be overcome.

Build them and they will come. Build casinos on their sovereign land, whether that sovereign land be out in the countryside far from a metropolitan center or right off I-95 not far from Ft. Lauderdale. Hire and train a workforce from among the tribal populace. Recruit and train executives from the tribe. Offer them all good-paying jobs. Supporters saw casinos as a way to change the fortunes of Native Americans, who more often than not toiled in rural outposts if able to find a place to toil at all.

So hats off to the folks who helped turn a brilliant idea into reality. Some gambling halls included enough amenities to appeal to the thinly populated location that welcomed the change of pace. Others went for the full package and added more later because the population supported it.

The Seminoles, located on both the west and east coasts of Florida, were the first to get in the game when they opened a high-stakes bingo parlor in 1979. Other tribes followed suit.

But bingo would soon be eclipsed.

In the Beginning

The Cabazon Band of Mission Indians in Southern California constructed the first Las Vegas-style casino on a reservation in the early 1980s. This development sparked a legal battle that ultimately reached the U.S. Supreme Court. The high court ruled in favor of the tribe in 1987, asserting that states did not have the authority to regulate tribal gaming on sovereign land. The landmark decision paved the way for a boom in Native American casinos, with hundreds now operating across the nation.

“The Cabazon decision recognizes a tribe’s sovereign right to game when not criminally prohibited,” Monique Fontenot, public affairs specialist for the National Indian Gaming Commission (NIGC), says.

Before the bricks and mortar provided a physical framework, before the staff trained for the various positions, the feds created a legal framework and in 1988 passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA).

And the states often memorialized the new relationship with individual tribal compacts—treaties, if you will—negotiated between the tribe and the government, often with a guarantee of some type of exclusivity for gaming offered to the tribe and revenue shared with the state.

In 1993, the NIGC added support and guidance to the tribal gaming industry regarding compliance under IGRA.

“Through our collaborative government-to-government dialogue with tribes, we have been able to better access the unique on-the-ground challenges that gaming operators face and, when possible, apply that feedback to regulatory policies,” Fontenot says.

Various tribes leveraged their sovereignty to establish gaming operations as a means to generate revenue, she says. Gaming profits funded community development, education, health care and other services, and ultimately helped foster economic independence.

These days, the NIGC helps over 240 federally recognized tribes that own, operate, or license gaming establishments in 29 states. “This number has generally increased over the years as tribes either obtained federal recognition, obtained land eligible for gaming or made the decision to enter gaming under IGRA in instances where they already had federal recognition and eligible land,” Fontenot says.

Seminole Hard Rock Hotel & Casino, Hollywood, Florida

Except for a handful of small casinos in south Florida, which were grandfathered in, the Seminole Tribe has a legal lock on others seeking entry. Through hard-fought litigation victories in the 1980s and 1990s, the tribe established an early beachhead in the modern casino world by building on its success with bingo, says Michael J. Anderson of Anderson Indian Law.

Those battles in Florida have served as a model of success for tribes nationwide, he says.

The Seminoles have proven to be one of the top tribal operators as their empire spread well beyond the boundaries of Florida, says Brendan D. Bussmann, managing partner of advisory firm B Global.

“One of their best decisions was picking up the Hard Rock brand to be able to build name and brand identity around the globe,” he contends. “It has helped them translate into multiple properties around the world for both gaming and non-gaming.”

Now, you have a host of tribes around the country that have followed similar paths and have the ability to go well beyond their existing footprint. “Tribes like the Poarch Band, Chickasaw, Cherokee, San Manual, Mohegan, and Mashancucket Pequot are just a few that are falling in similar fashion to diversify their portfolios beyond their tribal lands,” Bussmann says.

More Money, More Problems

However, such success doesn’t mean issues won’t rise to the forefront. Problems to deal with—cyberthreats, for example. Some of the biggest commercial gaming companies have not proven immune to such attacks. Neither will tribal ones unless they can keep pace with modernization and innovation to ward off such threats, Fontenot says.

“As bad actors become more sophisticated in identifying and taking advantage of system and process vulnerabilities, gaming operators need to remain prepared and use strong internal control protocols to mitigate risks and keep tribal assets protected,” she asserts.

Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Sacramento at Fire Mountain is owned by the Estom Yumeka Maidu Tribe of the Enterprise Rancheria.

Competitive growth for customers could also be a factor in coming years. Tribal gaming halls compete with commercial versions unless exclusivity rules say otherwise. California only permits tribes to build Las Vegas-style casinos, says James Siva, chairman of the California Nations Indian Gaming Association (CNIGA). But other states such as New York have both elements.

Even a well-heeled organization like the Seminoles faces competitive issues despite exclusivity.

The grinding litigation against the Seminoles by a pair of small parimutuel companies—West Flagler Associates and Bonita-Fort Myers Corp.—trying to stop the tribe from monopolizing sports betting has proven to be thornier than expected. The Seminoles believe they will prevail, but the high courts might have a say.

“More recently, the tribe’s partnership with local governments and the Florida state government have yielded immense opportunities for mutual benefit. The Seminole Tribe has a solid history of working across the aisle with both political parties and their governors in Florida,” Anderson says.

The Seminoles are also at a development crossroads as they continue to expand upon their brand, Bussmann says. “As they have had successful property launches in other U.S. states, they currently have two major projects that they will need to deliver on with the transformation of the Mirage in Las Vegas and the building out of an integrated resort in Athens, Greece at the Hellinikon.”

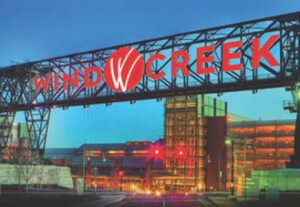

Wind Creek Bethlehem Casino & Resort is owned by Poarch Band of Creek Indians

Both are big projects that require strong execution on top of the other projects they have in the pipeline or bidding on in New York City. The Big Apple has three downstate casinos the state expects to divvy out when they finalize the locations and solicit bids. At least one could end up in Manhattan, Bussmann says.

“That continues to be a development focus in addition to their hotel offering in Times Square. A lot of the more major opportunities for expansion at this point are going to be international, as there are becoming few opportunities in the U.S. until you see some constitutional amendments changed in states like Georgia and Texas,” he says.

California has 66 tribal gaming establishments operated by 63 tribes, which is the greatest number of tribes engaged in gaming in any state, Siva says. Oklahoma claims more gaming establishments, though they are operated by fewer tribes than California.

“Keep in mind that, though some regions have widely spaced clusters, altogether they are scattered across a state that is roughly the size of Spain,” Siva says. “Some are a little more fortunately located near densely populated areas than others, but that has little to do with having a significant number of establishments.”

The advantage is that they often share many common interests, which is where an organization like CNIGA is important, as a forum for them to take collective action on issues of importance to them.

The Hard Rock’s expansion in California through its partnership with the Enterprise tribal casino north of Sacramento shows how the market models, branding and standards can be exported beyond Florida. “Other tribes like the Poarch Band of Creek Indians and the Chickasaw Nation are also developing tribal or commercial establishments away from their home state territories,” Anderson says.

Looking Ahead

Tribes have proven to be strong economic partners with hundreds of successful ventures with outside investors. To help in that score, the NIGC offers to review loan and development agreements prior to execution to ensure they comply with IGRA.

Among the biggest issues at the moment are California’s commercial card rooms offering what Siva calls illegal house-banked games at their establishments in violation of the California Constitution. California card rooms may only collect a fee/rake from each hand. But the card rooms have skirted the issue by a set of regulations that have passed muster in many courts, Siva says.

CNIGA is supporting Senate Bill 549, which seeks to give tribes standing in state court for a one-time-only lawsuit to resolve the legality of these games. “The fact that commercial card rooms are fighting this bill so hard is really telling, as a positive outcome for tribes is not guaranteed, and if card rooms feel that what they are offering is legal, they should be eager to have their day in court,” Siva argues.

Another big issue for tribes is ensuring that the state doesn’t overstep its bounds in the tribal-state compacting process and asks only what’s proper of tribes in the compact provisions. “Recently, the courts have sided with tribes, who have won some big decisions,” Siva says.

There is also the matter of state mismanagement of the Indian Gaming Special Distribution Fund (SDF), which is one of two funds that tribes pay into in California that is supposed to pay for the state’s cost to regulate tribal gaming, provide mitigation funds for the impacts of tribal developments and contribute to the cost of the state’s problem gambling programs, Siva says.

Two state audits, one at the behest of CNIGA, revealed that the state had been using the fund to pay for commercial card room regulatory activities, something not permitted by law, as well as allowing it to collect a massive reserve fund that far exceeds what most good government organizations recommend, Siva says. To begin to address the issues, CNIGA sponsored successful legislation last year to implement time tracking on regulatory activities at the Bureau of Gambling Control and is working on legislation to begin shrinking the excess reserve in this year’s legislative session.

“CNIGA is also holding talks on the other fund tribes pay into, the Indian Gaming Revenue Sharing Trust Fund, which disburses funds to tribes who have limited or no gaming. Discussions are centered around possible ways to increase funding disbursements to eligible tribes,” Siva says.

As more states pursue legalization and licensing of commercial online sports betting without an equally strong offering to tribes, the bottom line will likely feel the strain, Fontenot says. “What exclusivity includes and how sports betting fits into the framework, in some cases, may be challenging.”

Certainly, California has had a challenging time in its attempt to be what could be the most successful state in the nation when it comes to sports betting.

California voters want to get sports betting right, and are wary of attempts that would recklessly expand gaming in the state, Siva contends. “Tribes share these same concerns and believe the slow approach is best. Voters in 2022 saw through the corporate operators’ ruse to ship revenues out of our state and handed Proposition 27, which favored commercial operators, one of the most lopsided defeats in California history.”

To be fair, the tribal community pushed Proposition 26, which suffered its own defeat. This year, outsiders tried to push an initiative that tribes opposed. The effort failed. “It is critical that tribal governments be included in any discussions relating to the legalization of sports wagering,” Siva says.

Despite the obstacles still facing the tribal gaming community, the future remains promising. Overall, there is a positive outlook for tribes as they continue to use gaming as an economic engine for their nations.

“Diversification continues to be important so as to not become too dependent on one source of income,” Bussmann says. “This is why tribes look at other businesses besides gaming as well as looking to other markets to expand their gaming expertise. It’s important to build upon these talents and expand for the future generations of the tribe and long-term sustainability.”