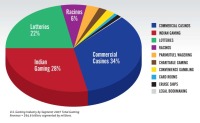

For years, tribal gaming revenues have been sneaking up on the revenue earned by commercial casinos. In 2008, tribal revenues accounted for 28 percent of all dollars gambled in the United States. The numbers are staggering. While U.S. commercial casinos won just over billion in 2008, revenues from tribal gaming halls weren’t far behind at .8 billion.

The casino gambling market share disparity is even more striking. From 1994, when commercial casinos enjoyed 80 percent of the gambling dollar in the U.S. to just under 20 percent for tribal casinos, the Indian gaming halls have made steady gains over the years. In 2008, commercial casinos dipped under 50 percent for the first time to 47.7 percent. Tribal gaming accounted for 42.6 percent and racinos 9.7 percent.

And things are poised to get even better with the ascension of Barack Obama as president. So far, he’s following through on his campaign promises of giving more opportunity to Indian Country. His meeting with tribal leaders in the White House soon after he took office signaled that his stated commitment to Indian Country will be followed out. Appointment of cabinet-level advisers on Native American affairs was also encouraging.

In the eight years of the Bush administration, the Interior Department rejected 10 of 12 tribal applications for federal recognition. In one of the first actions of the Ken Salazar-led Interior, the Shinnecock tribe of Long Island, New York was recognized after years of trying.

While nothing official has been declared, the “commutability” doctrine of the Bush administration-where land-into-trust status would only be granted if it was a reasonable distance from the tribe’s reservation-has quietly been shelved.

Off-reservation efforts in New York, California and elsewhere have the support of key members of Congress, which could result in new large casino facilities close to major cities like New York and San Francisco. And the shadow of the Carcieri Supreme Court decision could be brightened by a “fix” supported by many members of Congress.

The appointment of Larry EchoHawk as head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the resignation of Phil Hogen as chairman of the National Indian Gaming Commission was generally seen as a help to the tribes that depend upon gaming as their economic engine.

But tribal gaming and commercial casinos have one thing in common: a tight credit market. Complicating the tribal lending atmosphere are pending defaults on several loans due in the next few years. How both the tribes and the lending institutions handle this situation could go a long way to either freeing up or freezing further investment in tribal government gaming.

But if the “new normal” includes a reasonable amount of faith in tribal gaming in the investment community, the supremacy of the commercial casinos could be at risk within a relatively short time.