n October 16-17, 2008, the Arizona State University School of Law hosted a conference at Fort McDowell Casino to commemorate and critically examine the 20 years of Indian gaming under the 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. The event attracted scholars, policy makers and tribal representatives from around the country, many of whom had participated directly in the creation and implementation of the act. Our paper examined the economic impacts of Indian gaming under IGRA and complemented the political work presented by other academics whose work examined the ways that IGRA resolved specific legal and regulatory dilemmas and allowed tribes to pursue Class III gaming without fear of federal criminal prosecution. An excerpt from the paper appears here:

The Growth of Indian Gaming

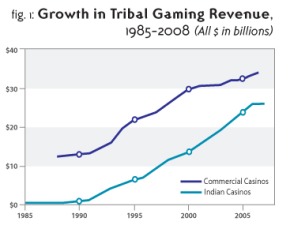

In recent years the NIGC has regularly released tables and charts reporting the gross gaming revenues of Indian casinos-that is, the total revenues net of prizes paid for every Indian bingo hall and casino across the country. Predictably when these data are released, commentators note the burgeoning Indian sector of America’s growing gambling industry.

Upon the release of the latest gaming revenue figures, which reached $26 billion in 2007, the commission chairman, Philip N. Hogen, noted, “The continued growth [of Indian gaming revenue] is significant considering recent economic struggles throughout the country. The Indian gaming industry has experienced tremendous growth since the inception of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act 20 years ago in 1988.”

The numbers warrant Hogen’s accolades of “significant” and “tremendous” (Chart 1). In inflation-adjusted terms, Indian gaming exploded more than a hundred-fold from $171 million in 1985 to $26 billion in 2007, for an average compound growth rate of 26 percent per year after inflation. As the light blue line in Chart 1 indicates, Indian gaming grew rapidly in comparison with the commercial casino sector as well, jumping from 2 percent of its size in 1988 to more than three quarters in 2007. Back in the opening days of bingo halls at Penobscot, Seminole, Shakopee and elsewhere, few observers had any inkling that such growth was in store for Indian Country. Yet while the growth of Indian gaming appropriately deserves its many superlatives, growth has not been uniform over time. (See fig. 1.)

To the human eye, the growth of Indian gaming revenue in the chart appears simply “exponential.” That it is, but there is more than meets the eye: the exponential growth is not consistently so. When the same data is portrayed on a log scale, wherein the intervals between grid lines change from constant increments in the chart to constant proportions, it becomes clear that the pace of Indian gaming growth had three major phases. On the log scale, steady rates of compound growth in Indian gaming revenue appear as straight lines, and there are three roughly straight-line periods in the graph. Up until 1988, compound annual revenue growth was modest-in the single digits. For the five years beginning in 1988, growth leapt to an average of 79 percent per year (light blue line in the chart). And beginning in 1993, growth cooled substantially to a steady 15 percent per year over the 1993-2007 period. Virtually no growth took place in the last of those years: growth was 0.4 percent after inflation. (See fig. 2.)

In fig. 2, the log scale shows steady compound growth rates as straight lines.

Abrupt corners in a graph like fig. 2 beg further examination. That Indian gaming grew quickly in the five years after IGRA probably does not strike knowledgeable participants from that time as news, but the period when that growth took place is striking in retrospect. The Supreme Court decided Cabazon in 1987, and IGRA became law in 1988. The coincidental uptick in growth points to the power of these actions to unleash capital flows-of both financial and human capital-to Indian Country. Clearly, Cabazon certified to the outside world the civil and regulatory freedoms tribes had been asserting, but did IGRA help too?

Legal and political observers, most importantly tribal leaders and representatives, often (and correctly) note that IGRA constrained American Indian powers of self-determination in gaming relative to what Cabazon afforded. But in a very real sense IGRA also lifted from Indian gaming the heavy burdens of political and regulatory uncertainty.

Of course, the effect was neither complete nor uniform. Gubernatorial recalcitrance held down investment in California for more than a decade after IGRA’s passage. “Friendly” and unfriendly lawsuits in Washington, New Mexico and elsewhere were necessary to settle the nature of compacting authority, game types, revenue sharing, and a host of other issues relevant to the Indian gaming investment climate. The Seminole decision, of course, vitiated a central congressional assumption in the compacting framework. Notwithstanding its shortcomings, however, IGRA went far in organizing the process by which state and tribal claims could be resolved.

Thus to the tribal leader’s correct observation that IGRA constrained Indian nations, the economist raises his familiar question: Compared to what? Wouldn’t Indian gaming revenue have continued at a slow pace of growth under a Cabazon-only rubric as it had done under a Butterworth-only framework?

Recall that state governors and members of Congress were up in arms about regulation and competition against non-Indian casinos. For how long would tribal governments have suffered slow gaming growth, and at what loss of net present value for tribes? Any delay in the arrival of the steep upward slope indicated by the light blue line in fig. 2 would carry consequences in the tens of billions of dollars for Indian Country.

It may forever be impossible to disentangle IGRA’s various abetting and hindering influences from Cabazon‘s broad acknowledgment of tribal regulatory authority because the two come so close together in time, but the acceleration in growth visible in fig. 2 raises the bar for those who lament the state compacting provisions in IGRA.

Yes, IGRA constrained the tribal sovereignty that is so essential to American Indian economic development. Yes, IGRA’s shortcomings as a framework for accommodating tribal and state interests effectively and efficiently are plainly evident.

On the other hand, is not five consecutive years’ worth of 79 percent compound annual growth a necessary proof that IGRA made investors-and tribes themselves-feel much more secure about directing resources toward Indian gaming development? How intensely were electronic gaming machine companies investing in Class II technologies before IGRA? How cheap and accessible was the capital necessary to create a Foxwoods, a Mystic Lake, or an Emerald Queen prior to IGRA, if at all? How readily were state governments cooperating to build highway off-ramps to Indian reservations? Good institutions of government make investors feel secure by reducing political, legal, and regulatory uncertainty, and IGRA, flawed as it was, created an environment that clarified tribes’ role in the federalist matrix of government-to-government relations in a way that was more than just good enough to get that job done. Would Cabazon alone have done as much? If so, when?

The second “corner” of fig. 2 comes in 1993 and presents puzzles in itself and perhaps even challenges the above explanation for the significant uptick in 1988. If IGRA created beneficial investment conditions in 1988, did something make them less attractive after 1993? If so, what? That year brought with it a new administration, and it is conceivable that BIA procedural changes introduced delays or uncertainties. A more plausible scenario is that in May 1994-the year growth fell substantially-Connecticut and Mohegan signed their gaming compact, which among other things extended Mashantucket Pequot’s 25 percent revenue-sharing terms to a second tribe. Perhaps that compact introduced higher stakes into compact negotiations around the country, thereby introducing uncertainty.

On the other hand, that compact extended statewide exclusivity to Mohegan, which would tend to accommodate growth in investment. It may also be the case that the uptick in 1988 was an accounting anomaly because revenues prior to IGRA were not centrally monitored as closely as they were after IGRA’s passage.

This explanation may be weakest because an improvement in the accuracy of reporting would probably not begin and end abruptly over five years. Whatever their underlying causes, the discontinuities in the revenue trend in Chart 2 are remarkable in their own right, and an invitation to more investigation.

The ASU conference looked retrospectively at 20 years of Indian gaming under the frameworks of IGRA, describing jurisdictional conflict, legal and regulatory unpredictability, and political change. As tribes and states look to the future, the global recession and financial market collapse compound the uncertainties.

Nonetheless, the story of economic growth achieved under a framework that settled the place of tribes in the federal system-at least for a few issues and a few years-holds out the promise that Indian gaming can grow rapidly again under conditions that the tribes and the federal government themselves have the power to create. With luck, the states will recognize their enlightened self-interest in supporting such growth as well.