On August 13, 2013, Rick Hill, chairman emeritus of the National Indian Gaming Association (NIGA), was asked to present a history of tribal government gaming and the role that NIGA has played in protecting and promoting gaming, both before and after the passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) in 1988.

At the time, IGRA was 25 years old, and Chairman Hill’s speech was both a renewed call to action and a prayer of gratitude to those who had created and sustained NIGA across the decades.

While his presentation was not recorded, this article is based on extensive written notes and a copy of the remarks made by Chairman Hill that day. I hope those who knew Rick Hill will hear his voice here, and those who didn’t can appreciate the legacy of NIGA through his words.

After an introduction by Sheila Morago, executive director of the Oklahoma Indian Gaming Association (OIGA), who invited him to give this address, Chairman Hill’s speech started out in a way that reflected his humility and humor. In only a few short words, he compelled those who were standing in the back of the room to put down their phones, move toward the podium, and listen.

“B-23… I-19… O-31…

“Hello, everyone, I thought Sheila asked me here tonight to call bingo numbers. The Catholic Church is still mad because we stole their sacred sacrament, bingo.

“Some of you may remember (poet and musician) Gil Scott-Heron, when he said, ‘I had said I wasn’t gonna write no more poems like this. I had said I wasn’t gonna write no more words down about people kicking us when we’re down. But the dogs are in the street. The revolution will not be televised.’”

As NIGA (#indiangaming1985) celebrates 35 years in 2020, we simultaneously mourn the loss of Rick Hill, who would undoubtedly have had the perfect words to share with Indian Country this year at the 2020 NIGA Indian Gaming Trade Show & Convention.

In what is sure to be one of many tributes to Chairman Hill, this article is meant to carry honor to him, to his family and to the Oneida Tribe, and to highlight the sacrifices they all made so he could dedicate himself to the work required to sustain NIGA across the decades.

NIGA’s Roots as a BIA Advisory Group

Frank Duscheneaux is considered by many to be the “father of IGRA,” (along with IGRA’s “mother,” Virginia Boylan). He believes it was Hazel Elbert who first recognized the need for a tribal advisory group to advise the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) on Seminole bingo and other forms of gaming being offered across Indian Country. Elbert started in 1967 and worked her way up to acting commissioner at the BIA. According to Duscheneaux, in the late 1970s, Elbert “put together a tribal advisory group, and the tribal representatives there took over a meeting in Oklahoma City.”

NIGA Chairman Emeritus Rick Hill with current Chairman Ernie Stevens

Rick Hill’s 2013 speech picked up the narrative from there. He recalled how the BIA “called an emergency meeting to gather facts about high-stakes bingo after a lot of complaining by the states. Mark Powless was elected chairman of what was being called the National Indian Gaming Task Force. Shortly after that, Senator Daniel Inouye organized a meeting to tell the tribes that if we do not get organized, we are going to get rolled by the states. Powless went coast to coast, visiting tribes to get recommendations for the task force.”

Hearings were soon held by the Senate to assess the impact of high-stakes bingo, which was estimated to be generating $100 million for tribal governments by then. According to Chairman Hill, “Tribes got tired of being the ‘think tank’ for the BIA, so tribal leaders convened a national meeting to discuss the need for protective legislation, and to establish the National Indian Gaming Association.”

NIGA’s first meeting in 1985 was a humble event: the first NIGA board and a group of tribal leaders met in a single hotel room with two small beds, since there were not sufficient funds (or participants) for a conference room.

But tribal gaming was expanding rapidly, and NIGA soon had 50 member tribes and provided testimony to Congress about tribal regulatory authority and the purposes of tribal gaming. At that time, NIGA also established an alliance with the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) committee on Indian gaming.

After the 1987 Cabazon decision clarified tribal regulatory authority, and the 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act provided a remedy for Johnson Act restrictions on slot machines through the vehicle of a tribal-state compact, the state of Minnesota signed the first compacts that, according to Rick Hill, “kept the focus on the economics of it—jobs.” Fittingly, the first two chairmen of NIGA were from tribes in Minnesota.

After Hill was elected NIGA’s third chairman in 1992, NIGA hired its first full-time staff, starting with Tim Wapato as the first executive director, Gay Kingman as director of public relations and Chuck Robertson as policy analyst. There were no records, no office beyond a kitchen table, and NIGA was in debt with no budget.

As Hill described it, “We had to build NIGA at the same time we maintained the fight. We set up the NCAI-NIGA Task Force, and created a board with 12 regions, two from each region. It was the perfect size, since we had exactly 12 chairs in the room. At that time, we decided that the mission of NIGA would be to promote tribal sovereignty and protect the principles of IGRA.”

Early Challenges

Once NIGA hired staff, Hill recalled, “Tim Wapato had to travel to many of our member reservations to ask for contributions. Early donations came in from Shakopee, Mashantucket Pequot, Oneida, Morongo, Prairie Island, Sycuan, Fort McDowell and SoDak. I remember that SoDak (an early equipment manufacturer, later bought by IGT) gave NIGA a big check to keep the doors open, but there were no cellphones, so I had to wait in the hotel room to see if we were going to get the check or not. I was afraid to leave, in case the call came while I was out of the room.”

Of course, at the same time NIGA was building its operations to protect tribal gaming, local governments and commercial casino operators were pushing for legislation to limit tribal jurisdiction or tax tribal gaming.

Long before Donald Trump became known for his one-liners, NIGA defeated two proposals that NIGA staff aptly named the “Harper Valley PTA legislation,” which would have included local governments in the tribal-state gaming compacting process, and the “Donald Trump Protection Act,” formally the congressional attempt in 1997 to extend the Unrelated Business Income Tax (UBIT) to tribal gaming.

As Hill recalled, “This legislation would have imposed a federal tax at a rate of 35 percent onto tribal governments engaged in Class II or Class III gaming. NIGA led an uprising from Indian Country to defeat the measure by one vote in the House, based on the fact that governments cannot tax other governments.

“Congressman JD Hayworth from Arizona stood by the tribes and Congressman Charlie Rangel said, ‘Is General Custer in the Room? Why are we going after the Indians?’”

In order to differentiate tribal gaming from corporate gaming during the UBIT threat, NIGA crafted a powerful and award-winning advertising campaign to defeat the measure with the slogan, “We Build Schools, You Buy Yachts.”

In addition to managing the legislative blowback after IGRA, NIGA attorneys, tribal gaming commissioners and tribal casino operators formed the NIGA-NIGC MICS (minimum internal controls) Taskforce to support the creation of a new federal regulatory agency, the National Indian Gaming Commission. Five years after IGRA, in 1993, Tony Hope was appointed the first NIGC chairman and Jana McKaeg and Joel Frank were appointed the first NIGA commissioners.

That same year, the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation signed the first gaming compact to include revenue sharing. In the 1996 Seminole decision, the Supreme Court strengthened states’ rights and “gutted some parts of IGRA.”

In another blow, Proposition 5 passed in California in 1998, and was then overturned. In his 2013 speech, Chairman Hill summed up this decade of the backlash against tribal gaming with his typical flair: “The federal and state governments are not afraid of organized crime, they are afraid of organized Indians.”

Federal Studies a Threat

By now, Chairman Hill’s historical overview was on a roll. He outlined the two years of travel and outreach that he and then-Executive Director Jacob Coin spent following the National Gambling Impact Study Commission (NGISC), to be sure they included the voices of Indian Country in its final report.

Then, he thanked those tribal leaders who continued to fight for tribal rights through a second study commission sponsored by the states: the Public Sector Gambling Study Commission, where he was appointed as a member.

These two study commissions revealed the breadth and depth of the opposition to tribal gaming. A partial list of opponents included the National Governor’s Association, the Western Attorneys General, multiple city mayors, the Leagues of Cities, religious groups, anti-Indian groups, commercial gaming companies in Las Vegas and New Jersey, Donald Trump, the National Coalition Against Legalized Gambling and the dog and horse racing industries.

These were busy times at NIGA, with Chairman Hill and others offering support for Proposition 101 in California, Proposition 202 in Arizona, and for the tribes in New Mexico as they threatened to block the interstate highway to protect their rights.

Beyond gaming, NIGA also supported the battle to unseat Senator Slade Gorton in Washington state, who pushed for “means testing” of tribal governments as a way to limit their federal rights and the government’s treaty obligations. Gorton’s defeat was a high point for Indian Country, and underscored NIGA’s philosophy that there was great strength in working together.

Again, Chairman Hill’s brilliant sense of humor as he retold these stories summed up this era in NIGA’s history perfectly: “You want a lifetime of work? Educate the white man about tribal sovereignty.”

Post-NIGA Activity

On a high note, with victories in California, Arizona and Washington, Chairman Rick Hill retired from NIGA in 2001, after nine years of nonstop travel and testimony. In a testament to his leadership through difficult times, he was the first tribal leader named to the American Gaming Association’s Gaming Hall of Fame, and was personally inducted by the AGA’s founder, Frank Fahrenkopf.

In the NIGA election of 2001, Ernie Stevens, Jr. was elected to follow Hill as chairman of NIGA. Like Hill, Chairman Stevens carries the legacy of all the NIGA founders who came before him. In closing his speech in 2013, Chairman Hill made a spontaneous roll call of those NIGA board members with whom he had worked. This list is not comprehensive, but reflects the names he mentioned spontaneously that day:

“Keller George, Jacob Viarrial, Clinton Pattea, Mark Powless, Jerry Hill, Frances Skenandore, Milo Yellowhair, Tim Martin, Tom Acevedo, Chairman Milanovich, Stan Crooks, Kurt Bluedog, John McCoy, Marge Anderson, Wendall Chino, Audrey Kohnen/Bennett…Steve Geller, Frank Fahrenkopf, the NIGC chairs, Tony Hope, Phil Hogen, Monty Deere, Harold Monteau…” And the list goes on….

Of course, Hill’s engagement with tribal government gaming did not end when he retired from NIGA. Rather, his work continued to reflect the best of tribal economic development and diversification. He played a lead role in the creation of the Four Fires hotel project in Washington, D.C., and the Three Fires project in Sacramento. He returned to tribal leadership as elected chairman of the Oneida Tribe back home in Wisconsin, and he continued to support his successor at NIGA, Stevens, his lifelong friend and athletic rival.

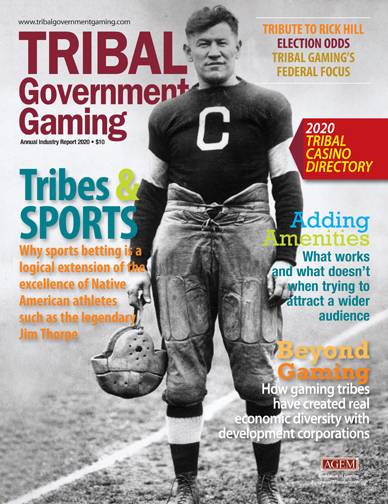

In 2019, now NIGA Chairman Emeritus, Hill was as busy as ever. One of his most high-profile projects was securing funding for a documentary called Bright Path, about Jim Thorpe, a Sac and Fox tribal member and Olympic champion, arguably the greatest athlete who ever lived. As a humble leader whose style was to lift up others, Rick was relentless in his pursuit of support for the film. He could be seen wearing (and distributing) sweaters with the letter “C” on them, in order to remind others that Thorpe attended Carlisle Indian School, where his athletic prowess was first on display.

In spite of these uplifting projects, Rick saw clearly that popular and political support for tribal sovereignty was never secure, and the legal attacks would keep coming, whether on tribal identity and families (the Indian Child Welfare Act) tribal land claims (the Carcieri decision), or tribal voting rights. As recently as the NIGA Tradeshow in San Diego in 2019, he asked me once again the one question that frames them all: “How can tribes expect to get a fair trial in a court that sits on stolen land?”

Rick Hill passed away on the Oneida Indian Reservation on December 13, 2019. Indian Country will never be the same. His humor, brilliance, generosity and wit were the foundation of NIGA during a turbulent time in tribal gaming’s history. They are an enduring legacy, both for those who knew him and those who came after, but continue to benefit from his tireless commitment to tribal rights.