Of the 38 states that have legal sports betting, tribes in 10 are a key factor. In some cases, Indian Country was the driving force behind legislation. In others, tribes agreed to pay taxes. And in still others, Indian Country is the only place consumers can place a bet.

The structure is different in nearly every state. And in the last 12 months, the rules have changed. The U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) is tasked with interpreting and implementing the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA). Passed by Congress in 1988, IGRA clearly allows for Class III gambling on tribal land. In February 2024, a new BIA interpretation made it clear that the federal government backs off-reservation digital sports betting if a state agrees.

Four months later, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear a case that made it so Florida’s Seminole Tribe not only has a monopoly, but can offer off-reservation digital sports betting. The tribe does not pay a tax, but does have a revenue-share agreement with the state. The case, in which two parimutuels sued Governor Ron DeSantis for signing a compact they believed was invalid, may well have created a roadmap for tribes in other states to follow.

Three of 10 Biggest Tribal States Don’t Have Legal Wagering

In July 2024, a Colorado tribe filed its own federal lawsuit, saying the state is denying it the opportunity to offer legal digital betting. Southern Ute Tribal Chairman Melvin Baker said at the time that because the case “held that the Seminole tribe was entitled to engage in statewide sports betting in Florida, any legal objection to the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain from engaging in statewide sports betting is gone.”

The case is currently with the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado, awaiting a response from the state and Governor Jared Polis. The deadline for his response in March 7.

The key difference between the Florida and Colorado lawsuits is that in Florida, the state wanted to make a deal with the Seminoles. In Colorado, that does not appear to be the case.

Nearly seven years after the Supreme Court gave states the right to decide if they wanted legal sports betting, three of the 10 states with the biggest number of tribes do not have it. In California, the tribes are clearly driving the conversation and have plans to bring a ballot initiative to legalize in 2028.

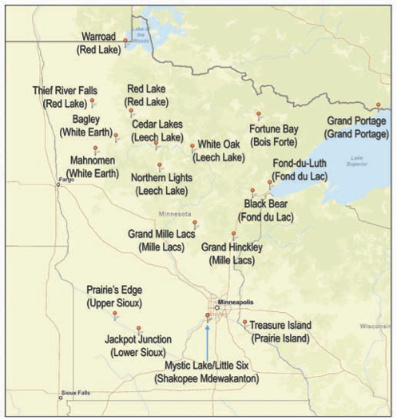

In Oklahoma, Indian Country is waiting for Governor Kevin Stitt to term-limit out for the chance. And in Minnesota, where the tribes, charitable gaming and horse racetracks seemingly hammered out a deal ahead of the 2025 session, hopes all but died in committee on the eve of Valentine’s Day.

For those states yet to legalize sports betting or considering online gaming, the current landscape offers much to study and learn from. Here’s a look at the highlights from 10 states in which Indian Country offers legal digital or retail sports betting.

Arizona

Tribes in Arizona gave up the right to exclusivity when they agreed to a deal in 2021 that allotted 10 digital sports betting licenses to Indian Country and 10 to professional sports teams. The hitch is that there are 16 gaming tribes and so far, only eight professional sports teams that meet that definition. So while six Arizona tribes are shut out of offering digital betting, there are two unclaimed pro-sports team licenses.

Tribes in Arizona gave up the right to exclusivity when they agreed to a deal in 2021 that allotted 10 digital sports betting licenses to Indian Country and 10 to professional sports teams. The hitch is that there are 16 gaming tribes and so far, only eight professional sports teams that meet that definition. So while six Arizona tribes are shut out of offering digital betting, there are two unclaimed pro-sports team licenses.

Under the terms of the compact, all of Arizona’s tribes can offer in-person wagering and digital betting on the reservation. But off reservation, the 10 tribes licensed to offer online sports betting are regulated by the state and pay the same 10 percent tax rate as commercial operators.

Colorado

There is currently no tribal digital sports betting in Colorado. In 2019, Colorado’s legislature was among the first to legalize digital sports betting after the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA) was overturned. At that time, the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute tribes opened retail sportsbooks and eventually began offering digital sports betting. Neither tribe paid tax to the state on bets taken in-person or online.

There is currently no tribal digital sports betting in Colorado. In 2019, Colorado’s legislature was among the first to legalize digital sports betting after the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA) was overturned. At that time, the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute tribes opened retail sportsbooks and eventually began offering digital sports betting. Neither tribe paid tax to the state on bets taken in-person or online.

The Southern Utes partnered with US Bookmaking and became the first tribe in the U.S. to offer off-reservation online wagering in 2020. But by 2023, both tribes had shuttered their sites due to a conflict with the Colorado regulator. Last summer, the Southern Utes filed suit against the state.

The Mountain Utes later joined. In the lawsuit, the tribes say the state has breached their existing gaming compacts, which date to the 1990s. The compacts allow the tribes to have “those gaming activities and bet amounts that are identical” to ones authorized in the state. In essence, whatever commercial operators are allowed to offer, the tribe can too.

But the state argues that while that may well be true, if the tribes want to offer digital betting, they should pay the state a 10 percent tax and be regulated by the state. The tribes argue that is a violation of their sovereignty. The workaround for many tribes in this situation is to pay the state a revenue share or a set fee for the right to offer digital betting.

According to the complaint, the state’s actions are “motivated by money. Sports betting regulated by Colorado is subject to a 10 percent tax, whereas no such tax could ever apply to tribal gaming under federal law. Therefore, the state sought to freeze the tribe out of internet sports betting.”

Baker said that his tribe has little appetite for legal action, but was forced to “take critical action to uphold equal and fair treatment of our sovereign rights.”

A solution would be to renegotiate the compacts and settle on annual payment to the state for the right to offer digital betting.

Connecticut

Like the Arizona tribes, Connecticut’s two tribes agreed to give up exclusivity and be regulated and taxed by the state. The Mashantucket Pequot and Mohegan tribes each have a casino retail sportsbook, and partnered with DraftKings and FanDuel, respectively, for digital wagering. The law they supported also allows the Connecticut Lottery to operate a digital platform and 15 stand-alone sportsbooks. The lottery first partnered with Rush Street Interactive, and then moved on to Fanatics Sportsbook.

Like the Arizona tribes, Connecticut’s two tribes agreed to give up exclusivity and be regulated and taxed by the state. The Mashantucket Pequot and Mohegan tribes each have a casino retail sportsbook, and partnered with DraftKings and FanDuel, respectively, for digital wagering. The law they supported also allows the Connecticut Lottery to operate a digital platform and 15 stand-alone sportsbooks. The lottery first partnered with Rush Street Interactive, and then moved on to Fanatics Sportsbook.

The tribes, like the lottery, are taxed 18 percent of adjusted gross revenue for digital betting. They also must adhere to any changes to the state law. There is currently a bill in the state legislature that would put a cap on how much a sportsbook can hold. The one-page proposal does not indicate what the maximum would be.

Florida

Florida’s Seminole Tribe may be the envy of tribes across the U.S. when it comes to gambling and compacting with the state. While Colorado’s tribes are suing in the hopes of getting a similar deal, the Seminoles and the state easily agreed to a hub-and-spoke model that not only allows the Seminoles to offer digital betting on their own platform, but gives them a cut of any sports betting offered by anyone else in the state. Parimutuels can partner with the Seminoles to offer sports betting, but must pay the tribe 40 percent of revenue.

Florida’s Seminole Tribe may be the envy of tribes across the U.S. when it comes to gambling and compacting with the state. While Colorado’s tribes are suing in the hopes of getting a similar deal, the Seminoles and the state easily agreed to a hub-and-spoke model that not only allows the Seminoles to offer digital betting on their own platform, but gives them a cut of any sports betting offered by anyone else in the state. Parimutuels can partner with the Seminoles to offer sports betting, but must pay the tribe 40 percent of revenue.

Under the terms of the 2021 compact, the Seminoles must pay the state $2.5 billion over the first five years in revenue share for all current forms of gambling. In total, the tribe agreed to pay the state $20 billion over 30 years. The Seminoles do not make their financials public.

The Seminoles own seven casinos around the state, and last November made an agreement with West Flagler and Associates (WFA)—the plaintiff in the federal case that could have nullified the compact—to offer betting on jai alai at WFA’s parimutuels.

In their deal, the Seminoles maintained their sovereignty and exclusivity. Having a 30-year compact that protects the tribe from being regulated and taxed by the state also means that the Seminoles are protected from the whims of the state legislature. In several other states, lawmakers have already increased sports betting taxes on commercial operators.

The compact lays the groundwork for the Seminoles to offer online casino, as well.

Michigan

The first state in which tribes agreed to be regulated and taxed by the state, Michigan’s tribal gaming setup is unique. Unlike in Arizona where there was a cap on the number of tribal betting licenses available, in Michigan, there is one per tribe. Indian Country did give up exclusivity by agreeing to a deal that allows the state’s three Detroit casinos—owned by Mandalay Entertainment, MGM and Penn Entertainment—one wagering platform each.

The first state in which tribes agreed to be regulated and taxed by the state, Michigan’s tribal gaming setup is unique. Unlike in Arizona where there was a cap on the number of tribal betting licenses available, in Michigan, there is one per tribe. Indian Country did give up exclusivity by agreeing to a deal that allows the state’s three Detroit casinos—owned by Mandalay Entertainment, MGM and Penn Entertainment—one wagering platform each.

But it also leveled the playing field for tribes. Many of Michigan’s tribes are in the northern part of the state or on the state’s Upper Peninsula, far from a major metropolitan center. But partnering with a commercial betting partner like Caesars Sportsbook (Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians) or DraftKings (Bay Mills Indian Community) created a significant new revenue stream despite location. In many cases, those companies also invested in the tribes’ retail casinos.

Sports betting platforms, including those tethered to a tribal casino, are taxed at 8.4 percent of gross gaming revenue. The digital sportsbooks are regulated by the Michigan Gaming Control Board.

Nebraska

Voters agreed to legalize sports betting on the November 2020 ballot and three years later the first bets were taken. The Winnebago Tribe is a key player on the Nebraska gaming scene, but in this case, the tribe is regulated and taxed by the state.

Voters agreed to legalize sports betting on the November 2020 ballot and three years later the first bets were taken. The Winnebago Tribe is a key player on the Nebraska gaming scene, but in this case, the tribe is regulated and taxed by the state.

State racetracks—not the tribes—can be licensed to offer betting, though the the Winnebago Tribe, through its commercial arm, Ho-Chunk, Inc., is operating the War Horse Casino brand in partnership with tracks in Lincoln, Omaha and Sioux City.

Lawmakers have been considering adding digital wagering, but have not done so yet.

New Mexico

In October 2018, the Santa Ana Star Casino near Albuquerque opened a sportsbook. There was no new law to allow sports betting and no compact renegotiation. Rather, the tribe believed that because it has exclusivity to Class III gaming and would be offering it on its land, that it would be permissible under IGRA.

In October 2018, the Santa Ana Star Casino near Albuquerque opened a sportsbook. There was no new law to allow sports betting and no compact renegotiation. Rather, the tribe believed that because it has exclusivity to Class III gaming and would be offering it on its land, that it would be permissible under IGRA.

The state attorney general’s office at the time said that it would “monitor” the situation and encourage the legislature to pass a law around sports betting. But five and a half years later, there is not one, and four other tribal casinos are also offering in-person wagering.

The upshot? New Mexico’s tribes have their own regulatory body and are not beholden to the state. They also do not pay taxes.

Oregon

Like New Mexico, Oregon’s tribes offer self-governed in-person sports betting. Tribal casinos already existed before PASPA was overturned.

Like New Mexico, Oregon’s tribes offer self-governed in-person sports betting. Tribal casinos already existed before PASPA was overturned.

The Oregon Lottery offers the only digital platform in the state in partnership with DraftKings. Once that launched, tribal casinos began to explore how they could get in the game. There is no state law that allows the tribes to compete with the lottery, but under IGRA, offering retail wagering on the reservations is legal.

The tribes do not pay gambling taxes.

Washington

While Florida might seem to offer a blueprint for tribal gaming, Washington state was a pioneer in terms of allowing it. The state legislature happily crafted a law that allowed Washington’s 29 tribes to add sportsbooks to their casinos. In 2020, when the legislature passed the law, the tribes said they did not want digital betting. It’s likely that will change over time, but Washington’s law allows tribes to self-govern betting, and they do not pay taxes.

While Florida might seem to offer a blueprint for tribal gaming, Washington state was a pioneer in terms of allowing it. The state legislature happily crafted a law that allowed Washington’s 29 tribes to add sportsbooks to their casinos. In 2020, when the legislature passed the law, the tribes said they did not want digital betting. It’s likely that will change over time, but Washington’s law allows tribes to self-govern betting, and they do not pay taxes.

The Washington tribes do pay 1.63 percent of net casino win to certain organizations, according to the American Gaming Association, but they remain sovereign and in control of gambling.

Wisconsin

In July 2021, the Oneida Nation announced that it had renegotiated its compact with the state to offer in-person sports betting. The deal happened quietly and is likely the first of 11 that will ultimately be made.

In July 2021, the Oneida Nation announced that it had renegotiated its compact with the state to offer in-person sports betting. The deal happened quietly and is likely the first of 11 that will ultimately be made.

At that time, Oneida Nation Chairman Brandon Yellowbird Stevens explained that the state’s tribal compact comes up for renegotiation in a specific order, and each has a “Me, too” clause. That essentially means that if one tribe can offer sports betting, then all others can negotiate it into their compacts.

No law was passed and betting is limited to on-reservation. But Wisconsin’s tribes have so far maintained sovereignty and exclusivity. They do not pay taxes to the state and are regulated by a tribal gaming commission.

A Case for Tribal Sports Betting

This tribal lawsuit could set a precedent beyond the West Flagler decision

A key date in the Colorado Ute tribes’ sports betting lawsuit against the state is looming. In October, Governor Jared Polis’ team filed a motion to have the case dismissed. By March 7, after multiple extensions, the Southern Utes and Ute Mountain Utes must respond.

How the court rules on the motion will determine whether the tribes’ claim that the state has cut them out of digital sports betting will move forward. If it does, the ultimate decision could be a game-changer for tribes around the U.S.

Per the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA), the tribes have the right to offer in-person sports betting on their reservations. In May 2020, the state of Colorado launched digital sports betting for commercial companies. Every major online sports betting company is live in the state, as well as some unique offerings, including BetMonarch, Circa Sports and Sporttrade. Missing are two tribal platforms, at least one of which was live for several years.

Days after the the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear West Flagler v. Haaland, the Southern Ute tribe filed against the state. The West Flagler case, decided in the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, made it legal for the Florida Seminoles to offer statewide mobile betting.

The Ute Mountain Utes joined the Colorado lawsuit in September. The case is in the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado. As it unfolds, tribes around the country will be watching, and one tribal attorney who wished to remain anonymous said if the court finds in the Ute tribes’ favor, the decision could be more far-reaching than the West Flagler decision.

‘Magic Language’ Needed?

At issue in Colorado—as it was in Florida—is whether or not the tribes can offer digital sports betting off the reservation. The difference is that there is specific language in the Seminoles’ 2021 compact that essentially deems a bet taken anywhere in the state is considered to have been placed in Indian Country if it flows through a server on tribal land.

“The Colorado compacts do not have that potentially magic language that deems that a bet is considered placed where received,” the lawyer said. “Whether or not you need that language is not clear, and this lawsuit may clarify that.”

If the court decides that the language is not needed in compacts, it could clear the way for tribes in other states to have an easier path toward offering online sports betting—and eventually iGaming.

State Wants Tribes to Pay Taxes

Another key issue in the case is whether or not the Ute tribes should be subject to the same 10 percent tax on gross gaming revenue that commercial operators pay. But tribes don’t generally pay taxes to the states in which they are located. Many do, however, pay a revenue share to the state.

For example, the 2021 Seminole-Florida compact requires that tribe to pay the state $500 million per year for the first five years of its 30-year deal. In total, the tribe committed to paying the state $2.5 billion for those five years.

In Colorado, the Ute tribes were offering digital betting without paying a tax or revenue share. Their compacts do not contemplate this and they don’t appear to address the issue in the lawsuit. Should the tribes agree to pay a tax, they would also be regulated by the state. Another option is to recompact and create a revenue share.

The West Flagler decision coupled with the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs draft final rules changed the landscape for tribal betting. The BIA specifically addresses digital wagering off tribal land. And it ultimately interprets IGRA to mean that tribes can take bets from anywhere in a state, if the bets run through tribal servers. But those are federal laws and regulations—tribes must still compact with their states.

“States and tribes are allowed to negotiate compacting solutions to off-reservation gaming,” former National Indian Gaming Commission chair Jonodev O. Chaudhuri said during a panel at the Global Gaming Expo in October. “That doesn’t automatically legalize all off-reservation gaming or all hub-and-spoke models.”

In Colorado, the Ute compacts, which date to 1995, do not directly contemplate digital gaming. And they don’t include the “magic wording.” The looming question is: Will that matter?

“In Part 293, (the BIA) was careful to use the word ‘may,’” the lawyer who requested anonymity said. “But the D.C. Circuit seemed to only be concerned that the person making the wager on state lands is complying with state law. I think the right reading of the D.C. Circuit is that you don’t need that language. You do need state law to make the wager lawful. But you don’t need to go so far as deeming the wager as placed at the site of the server.”

“The Bedford at Foxwoods Resort Casino will provide diners with a glimpse into the way I entertain and host at my farmhouse in Bedford, New York,” said Stewart. “We have worked so hard to perfect this beautiful and inviting space, as well as curate a delicious variety of my most favored food and beverage recipes, which we are excited for guests to enjoy later this year.”

“The Bedford at Foxwoods Resort Casino will provide diners with a glimpse into the way I entertain and host at my farmhouse in Bedford, New York,” said Stewart. “We have worked so hard to perfect this beautiful and inviting space, as well as curate a delicious variety of my most favored food and beverage recipes, which we are excited for guests to enjoy later this year.” “Back when Foxwoods opened in 1992, the tribe had always wanted to do an indoor water park,” he elaborates. “And there were a lot of conversations over the years. There was even one called Pequot Island, where it was going to be an indoor water park run by the tribe. Unfortunately, that never came to fruition, but the tribe consistently had been in conversations with operators who were looking to do it themselves. We got very close in 2007 with Great Wolf Lodge, but then the recession hit.

“Back when Foxwoods opened in 1992, the tribe had always wanted to do an indoor water park,” he elaborates. “And there were a lot of conversations over the years. There was even one called Pequot Island, where it was going to be an indoor water park run by the tribe. Unfortunately, that never came to fruition, but the tribe consistently had been in conversations with operators who were looking to do it themselves. We got very close in 2007 with Great Wolf Lodge, but then the recession hit.

Tribes in Arizona gave up the right to exclusivity when they agreed to a deal in 2021 that allotted 10 digital sports betting licenses to Indian Country and 10 to professional sports teams. The hitch is that there are 16 gaming tribes and so far, only eight professional sports teams that meet that definition. So while six Arizona tribes are shut out of offering digital betting, there are two unclaimed pro-sports team licenses.

Tribes in Arizona gave up the right to exclusivity when they agreed to a deal in 2021 that allotted 10 digital sports betting licenses to Indian Country and 10 to professional sports teams. The hitch is that there are 16 gaming tribes and so far, only eight professional sports teams that meet that definition. So while six Arizona tribes are shut out of offering digital betting, there are two unclaimed pro-sports team licenses. There is currently no tribal digital sports betting in Colorado. In 2019, Colorado’s legislature was among the first to legalize digital sports betting after the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA) was overturned. At that time, the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute tribes opened retail sportsbooks and eventually began offering digital sports betting. Neither tribe paid tax to the state on bets taken in-person or online.

There is currently no tribal digital sports betting in Colorado. In 2019, Colorado’s legislature was among the first to legalize digital sports betting after the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA) was overturned. At that time, the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute tribes opened retail sportsbooks and eventually began offering digital sports betting. Neither tribe paid tax to the state on bets taken in-person or online. Like the Arizona tribes, Connecticut’s two tribes agreed to give up exclusivity and be regulated and taxed by the state. The Mashantucket Pequot and Mohegan tribes each have a casino retail sportsbook, and partnered with DraftKings and FanDuel, respectively, for digital wagering. The law they supported also allows the Connecticut Lottery to operate a digital platform and 15 stand-alone sportsbooks. The lottery first partnered with Rush Street Interactive, and then moved on to Fanatics Sportsbook.

Like the Arizona tribes, Connecticut’s two tribes agreed to give up exclusivity and be regulated and taxed by the state. The Mashantucket Pequot and Mohegan tribes each have a casino retail sportsbook, and partnered with DraftKings and FanDuel, respectively, for digital wagering. The law they supported also allows the Connecticut Lottery to operate a digital platform and 15 stand-alone sportsbooks. The lottery first partnered with Rush Street Interactive, and then moved on to Fanatics Sportsbook. Florida’s Seminole Tribe may be the envy of tribes across the U.S. when it comes to gambling and compacting with the state. While Colorado’s tribes are suing in the hopes of getting a similar deal, the Seminoles and the state easily agreed to a hub-and-spoke model that not only allows the Seminoles to offer digital betting on their own platform, but gives them a cut of any sports betting offered by anyone else in the state. Parimutuels can partner with the Seminoles to offer sports betting, but must pay the tribe 40 percent of revenue.

Florida’s Seminole Tribe may be the envy of tribes across the U.S. when it comes to gambling and compacting with the state. While Colorado’s tribes are suing in the hopes of getting a similar deal, the Seminoles and the state easily agreed to a hub-and-spoke model that not only allows the Seminoles to offer digital betting on their own platform, but gives them a cut of any sports betting offered by anyone else in the state. Parimutuels can partner with the Seminoles to offer sports betting, but must pay the tribe 40 percent of revenue. The first state in which tribes agreed to be regulated and taxed by the state, Michigan’s tribal gaming setup is unique. Unlike in Arizona where there was a cap on the number of tribal betting licenses available, in Michigan, there is one per tribe. Indian Country did give up exclusivity by agreeing to a deal that allows the state’s three Detroit casinos—owned by Mandalay Entertainment, MGM and Penn Entertainment—one wagering platform each.

The first state in which tribes agreed to be regulated and taxed by the state, Michigan’s tribal gaming setup is unique. Unlike in Arizona where there was a cap on the number of tribal betting licenses available, in Michigan, there is one per tribe. Indian Country did give up exclusivity by agreeing to a deal that allows the state’s three Detroit casinos—owned by Mandalay Entertainment, MGM and Penn Entertainment—one wagering platform each. Voters agreed to legalize sports betting on the November 2020 ballot and three years later the first bets were taken. The Winnebago Tribe is a key player on the Nebraska gaming scene, but in this case, the tribe is regulated and taxed by the state.

Voters agreed to legalize sports betting on the November 2020 ballot and three years later the first bets were taken. The Winnebago Tribe is a key player on the Nebraska gaming scene, but in this case, the tribe is regulated and taxed by the state. In October 2018, the Santa Ana Star Casino near Albuquerque opened a sportsbook. There was no new law to allow sports betting and no compact renegotiation. Rather, the tribe believed that because it has exclusivity to Class III gaming and would be offering it on its land, that it would be permissible under IGRA.

In October 2018, the Santa Ana Star Casino near Albuquerque opened a sportsbook. There was no new law to allow sports betting and no compact renegotiation. Rather, the tribe believed that because it has exclusivity to Class III gaming and would be offering it on its land, that it would be permissible under IGRA. Like New Mexico, Oregon’s tribes offer self-governed in-person sports betting. Tribal casinos already existed before PASPA was overturned.

Like New Mexico, Oregon’s tribes offer self-governed in-person sports betting. Tribal casinos already existed before PASPA was overturned. While Florida might seem to offer a blueprint for tribal gaming, Washington state was a pioneer in terms of allowing it. The state legislature happily crafted a law that allowed Washington’s 29 tribes to add sportsbooks to their casinos. In 2020, when the legislature passed the law, the tribes said they did not want digital betting. It’s likely that will change over time, but Washington’s law allows tribes to self-govern betting, and they do not pay taxes.

While Florida might seem to offer a blueprint for tribal gaming, Washington state was a pioneer in terms of allowing it. The state legislature happily crafted a law that allowed Washington’s 29 tribes to add sportsbooks to their casinos. In 2020, when the legislature passed the law, the tribes said they did not want digital betting. It’s likely that will change over time, but Washington’s law allows tribes to self-govern betting, and they do not pay taxes. In July 2021, the Oneida Nation announced that it had renegotiated its compact with the state to offer in-person sports betting. The deal happened quietly and is likely the first of 11 that will ultimately be made.

In July 2021, the Oneida Nation announced that it had renegotiated its compact with the state to offer in-person sports betting. The deal happened quietly and is likely the first of 11 that will ultimately be made.

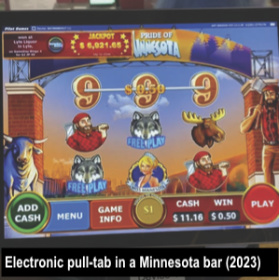

Minnesota hosts one of the nation’s largest charitable gaming markets, dominated by pull-tab operations. While traditional charitable gaming activities like raffles and bingo continue to serve rural and urban communities alike, they represent less than 5 percent of charitable gaming receipts. The real engine of charitable gaming lies in pull-tabs, especially their electronic variant.

Minnesota hosts one of the nation’s largest charitable gaming markets, dominated by pull-tab operations. While traditional charitable gaming activities like raffles and bingo continue to serve rural and urban communities alike, they represent less than 5 percent of charitable gaming receipts. The real engine of charitable gaming lies in pull-tabs, especially their electronic variant.