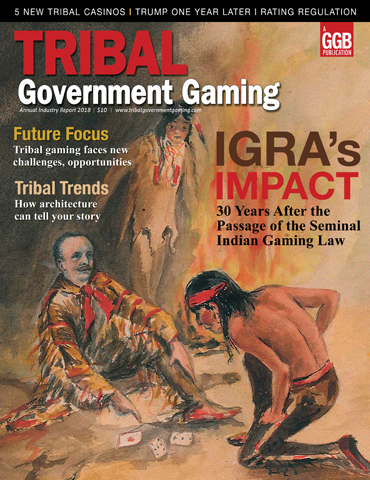

Nearing the 30th anniversary of the federal law that swung open the door to American Indian casinos, tribal governments are pondering a plethora of opportunities to expand their now-$31.2 billion industry.

Unfortunately, indigenous governments also face a number of challenges.

Sports wagering, internet gambling, daily fantasy sports (DFS), online poker, eSports, skilled games and a myriad of technological innovations are taking center stage at commercial and tribal government gambling conferences and trade shows.

The evolution from slot machines to hand-held, mobile entertainment—a convergence of video games and gambling—promises to entice the industry to a younger, more skilled gambler.

The potential for legalized sports betting is front and center with the U.S. Supreme Court, poised to possibly strike down the constitutionality of the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA). Roughly 20 states have introduced anticipatory legislation in the eventuality PASPA is wiped off the books.

Sports wagering and other new forms of gambling provide opportunity for commercial casinos, racinos and parimutuel operations as well as card rooms, lotteries and other state-regulated and taxed gambling vendors. Cash-strapped states are salivating at the tax revenues.

But tribes operate casinos under provisions of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) of 1988, which limits the scope of wagering allowed on tribal trust lands. Revenue from tribal casinos fund education, health care and social and government services to indigenous citizens.

Tribal-state regulatory agreements, or compacts, required under IGRA define the types of gambling permitted on some 248 tribal reservations in 29 states. New or amended compacts would need to be negotiated for tribes to offer sports betting or other Class III games.

IGRA also limits tribes to the types of gambling already allowed in the states in which they are located. Sports betting and other types of games may require legislation or ballot initiatives needing approval from two-thirds of the voters.

And always, tribes are subject to often-volatile state politics and demands for shares of revenue in exchange for new forms of compacted gambling. Tribes in at least 10 states pay casino revenue shares to states in exchange for exclusivity provisions in their compacts. Other tribes also pay funds to county and municipal governments.

Tribes dominate the casino industry in a number of states, including California, Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Washington, Minnesota, Florida and Michigan, to name a few. But tribal leaders in those states are uncertain the legal, regulatory and political hurdles they must leap to operate sports betting are worth a business generating a profit margin of only 4-6 percent.

Tribal leaders also fear sports wagering and other new forms of expanded gambling will create additional competition from commercial casinos, lotteries, card rooms, racetracks and racinos and other vendors, posing a threat to the viability of the tribal casino industry.

Most of the already-introduced sports wagering legislation would route betting on professional and college games through existing tribal and commercial casinos and parimutuel racetracks. A few call for lottery commissions to oversee sports wagering. Some bills require on-site wagering. Others permit online betting.

A Threat or an Opportunity

The National Indian Gaming Association (NIGA), the trade association and lobby for the tribal government gambling industry, formed a Sports Betting Working Group to tour the country, informing tribes about the new forms of gambling likely to sprout up in Indian Country.

The March road show included stops in Las Vegas, Seattle, Oklahoma City and Washington, D.C. NIGA’s executive board will issue a statement on sports betting at their April convention and trade show in Las Vegas.

“We need to find out if Indian Country is ready to move ahead if there is a full or partial repeal” of PASPA, Debbie Thundercloud, NIGA chief of staff, told Legal Sports Report. “So far the reaction has been mixed.

“There are some tribes that aren’t supportive and don’t think it’s the direction to go. Others are careful because they know the internet piece is connected. That may be the wave of the future, no matter what any of us wants or thinks at this point.”

NIGA Chairman Ernie Stevens addressed the issue in October testimony before the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs.

“As this committee examines issues and opportunities to help Indian gaming succeed over the next 30 years, we urge you to work with other committees of jurisdiction in closely examining emerging markets such as internet gaming, daily fantasy sports and sports betting,” he said. “These activities pose both potential expansion opportunities and challenges to existing tribal gaming operations and tribal-state compact agreements.”

One skeptic is Henry Buffalo, a Wisconsin attorney who helped draft IGRA. Buffalo fears the impact sports betting and internet gambling will have on land-based tribal operations.

“My thought is that tribes should avoid it like the plague,” Buffalo says. “If there’s anything that could end this cycle of opportunity that’s been around for 25 years or so, it could be that.”

Some see potential expansion as an opportunity.

“I think it will be an era of opportunity, absolutely, unless the country runs out of money,” says Chris Stearns, chairman of the Washington State Gambling Commission. “The opportunity will always be there. How we get there is not always easy.”

Others share Buffalo’s concern that expanded and mobile gambling may limit the social and economic progress tribes have achieved with IGRA and land-based casinos. They warn that the legal cloud over the ability of tribes to accept wagers from beyond reservation borders remains.

“I think internet gaming is a serious risk,” says Kevin Washburn, former U.S. assistant secretary of Indian affairs and professor of law at the University of New Mexico. “And sport betting is a bit of a risk.

“Tribes do not have a natural, comparative advantage on internet gaming. I fear for tribes with regard to those issues. I think in the future—young people live with their phones—the market is likely to change. And internet gaming is not an issue that is entirely resolved.”

“Technology is going to have an impact on tribal gaming,” agrees Joe Valandra, consultant and former chief of staff for the National Indian Gaming Commission. “For no other reason than the market demographics are changing. People live their lives through their phones.”

Washburn is confident tribes have established themselves politically at the state level to protect their economic interests.

“Tribes are becoming pretty sophisticated around state capitals,” Washburn says.

Playing Politics

Tribal gambling wields political clout in California, Florida, Minnesota and several other states. In fact, tribes dictate gambling policy in many of the 29 states in which they operate casinos. State officials won’t be quick to expand commercial gambling options, jeopardizing the jobs and revenues tribal casinos generate through their compact exclusivity provisions.

“If you are a vendor thinking of moving into some big-market states—whether it’s California or New York or Florida—you are going to have to deal with the tribes,” Stearns says. “You don’t just walk in and turn on the lights.

“Whether you have to deal with exclusivity or whether you have to push a boulder uphill in the legislature, you are going to have to work something out with the tribes. It may not be what you want.”

But Washburn notes that in many states the tribal monopoly on casino gambling is artificially created. It was the result of a federal act (IGRA) in response to a U.S. Supreme Court decision in California v. Cabazon (1987), which cognized the sovereign right of tribes to operate gambling on Indian lands without interference from the state.

With the continuing expansion of commercial and online gambling—casinos, racinos, sports and online gambling—tribal gambling becomes increasingly constricted, threatening the flow of government revenues to indigenous communities.

“Artificial monopolies don’t last forever, and this was artificial. It was created by law,” Washburn says of IGRA and Indian gambling. “Whether this lasts for five years or 80 years, no one knows. But it won’t last forever.

“There will be places where it will last longer because tribes will be able to address these issues in state legislatures. They will maintain their monopolies. But that will begin to crumble to the extent that the industry becomes nationalized.”

“I don’t know if tribes will be able to stay ahead,” Valandra says. “They can certainly compete. Where tribes contribute a fair amount of economic development and certainly revenue sharing payments to a state, they have leverage.

“That’s what the Florida Seminoles have. That’s what tribes in California have. That’s what tribes in Wisconsin have.

“They contribute so much money and jobs and other things they have the political leverage to stay competitive,” Valandra says. “They can prevent the expansion of state non-Indian gaming.

“Meanwhile, adopting technologically and staying ahead of the curve—that’s the challenge you face in any business.”

Much of the motivation to expand legal gambling will come from state budget deficits and the need for additional taxes. States will also follow the money. The urge for expanded gambling may threaten tribal exclusivity.

“It could become tenuous if lawmakers in a particular state believe they’re losing out to competition from other states,” Stearns says.

“If the state next door expands gambling, a state may want to follow the course. Where is the money going? If the money starts leaving the state, people will be looking to different courses of action.”

Things Might Take Time

The trade media is bullish on gambling expansion, anticipating that in the next five years or sooner there will be wagering on sports in as many as 32 states, generating a market of $6 billion or more. Many pundits believe the way is being greased by the speed in which many jurisdictions have legalized DFS.

Some experienced in state politics dispute that forecast. Gambling has never been an easy card for a state politician to play. Many of the 20 states where bills have been introduced to legalize sports betting—California and Minnesota among them—indicate little support for the legislation.

The margins on sports gambling are slim, so it’s not likely to put much of a dent in a state budget deficit. And some states will require a two-thirds vote for approval.

“This is going to take some time,” veteran gambling attorney Stephen Hart says of sports betting. “The idea it will spread across the country tomorrow, that’s not going to happen. Whatever happens, it’s going to take some time: five years, something along those lines.”

“It really is a five-year road for most states,” agrees David Grolman, vice president of operations for William Hill.

Sports gambling is defined as Class III gambling under IGRA, so there’s the tribal-state compacts—and potential revenue sharing—to negotiate, along with approval by the Department of the Interior.

“The compact changes are not that difficult in most jurisdictions,” Hart says. “In some states like California, there’s the added complexity of do we need a constitutional amendment. I think it would be a lot better for tribes if there were a federal statute.”

“States like Minnesota, Florida, California, are reluctant to mess with what they already have,” Valandra says of economic partnership tribes enjoy in many states.

The small profit margins may calm the interests.

“I think sports betting legislation will move a little bit slower when people get a sense of how much money we are really talking about,” Stearns says.

Partial Ruling May Hurt Tribes

Some tribal advocates fear justices will limit their PASPA ruling to a 10th Amendment finding for the states, leaving stand the act’s prohibition for sports wagering on tribal lands.

“The bifurcation issue is academically interesting, but the Supreme Court is unlikely to leave standing a ban on sports betting for tribes after knocking it down for the states,” Indian law attorney Frances Sjoberg says.

PASPA’s legislative history shows an effort by Congress to limit sports wagering for both tribal and state governments, she says.

“If Congress set a level playing field for states and tribes, it does not make sense for the Supreme Court to decide otherwise,” she says.

But Aurene Martin, president of Spirit Rock Consulting and a former high-ranking official with the Department of the Interior, notes that tribes have suffered a string of damaging rulings from the Supreme Court.

“I always worry about things like this,” she says.

Leaving tribal prohibitions in PASPA would require tribes to seek a congressional fix, which might be difficult with the vast array of politically powerful stakeholders on the sports betting issue, including television networks and sports leagues.

“I don’t know if we would prevail,” Martin says.

“We need to make sure that we’re seen as equal to the states,” says Damon Sandoval, a councilman for the Morongo Band of Mission Indians, in a Capitol Hill lobby effort that should include a ban on internet wagers.

“Otherwise it does us no good. We all have brick-and-mortars and we need to protect our investments,” Sandoval says of the largely rural reservation casinos.

IIpay Case Draws Attention

The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals convened in San Francisco last month to hear oral arguments in the case of Desert Rose Bingo, an online operation by the Iipay Nation of Santa Ysabel that was shut down in October 2014 by the state of California and federal officials.

The ruling will have a legal impact on the use of the internet in the operation of gambling on Indian lands. IGRA generally restricts wagering to the reservation. Santa Ysabel contends through proxy play and servers on tribal lands, the wager technically occurs on the reservation.

What is already significant in the Desert Rose case is the lower-court ruling upholding the status of Class II bingo gambling—with the internet as a technological enhancement—as being outside the tribal-state compact and state jurisdiction.

The court ruled, however, that the gambling was prohibited by the Unlawful Internet Gaming Enforcement Act (UIGEA) in that the wager occurred off Indian lands in violation of federal law.

Valandra, whose Great Luck LLC launched Desert Rose, contends tribes have an advantage in utilizing online forms of Class II, bingo-style gambling within property or reservation boundaries.

“That’s been the focus since the very beginning,” Valandra says of the Desert Rose legal battle. “Whether Great Luck makes a dime out of it or not, it will certainly change the opportunity for tribes to participate in using the internet for tribal gaming.

“If the 9th Circuit Court rules in our favor, that will open up the world for tribes.”

Tribes in attempting to maneuver through the legal minefield of IGRA limits and tribal-state compacts should explore opportunities of Class II games, he says.

“That’s an advantage tribes have, but it isn’t—to my chagrin—often talked about,” Valandra says.

Tribes Holding Their Breath

The commercial gambling industry is unequivocally pressing for legal sports gambling. The American Gaming Association, the commercial industry lobby, estimates $150 billion a year is wagered illegally on sports.

“We support legal, regulated gaming in this country,” AGA CEO Geoff Freeman says.

A 2017 study by Oxford Economics done for the AGA predicts sports betting could become a $41.2 billion industry, generating $3.4 billion in state and local taxes. Gambling under IGRA is not subject to taxation.

Tribes are not as enthusiastic.

“Everyone is just holding their breath,” Stearns says. “The tribes are not going to jump the gun and say, ‘Let’s get into this,’ then find out in March or April it’s not going to happen,” he says of the potential for a ruling that does not overturn PASPA.

“The general consensus is you’ve got 12, 13 states eager to jump in. There are definitely people who would like to see it.”

Much of the initial excitement dissipated with the anticipated limited earnings.

“Sports betting lost its mojo,” Jason Giles, executive director of the NIGA, told Pechanga.net.

John Repa, president of Hospitality and Gaming Associations, joins sports book operators in warning tribes against over-optimistic revenue projections. He also cautions about the high capital costs and labor demands.

“But the truth of the matter is there is a lot of pent-up demand” for legal sports gambling, he says.

Tribes may play down their potential investments from opening a distinct sports book to integrating wagering into a restaurant-bar or installing a kiosk.

In any event, tribes will need to evolve along with the rest of the gambling industry. The change, however, from urban to rural tribes, will not be even throughout Indian Country.

“Tribes are very different from one another, economically,” Stearns says. “What is going to work for one tribe is not going to work for another. The interests in Indian Country are not monolithic.

“Eventually, however, things will change,” including, he says, “a convergence of video games and gambling.”

“The future isn’t going to be slot machines, craps and roulette,” Stearns says. “It’s going to be dropping bombs on planes and running away with zombies.”

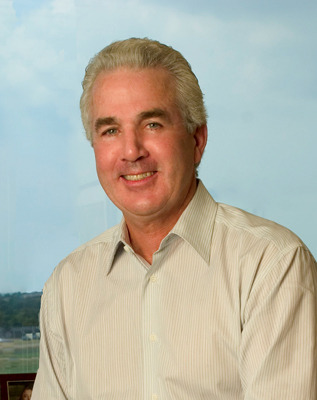

The story of the Bear River Band of Rohnerville Rancheria’s (Bear River) success cannot be told without discussion of the significant contributions made by John McGinnis; however, the story must begin prior to his involvement. In fact, it dates back to the California Rancheria Termination Act of the 1950s and 1960s. Bear River was a terminated and landless tribe, and was not reinstated until 1983, after which they spent years working out of an old building in Eureka, California. Not until 1991 did grant money allow Bear River to relocate to its current location in Loleta, California.

The story of the Bear River Band of Rohnerville Rancheria’s (Bear River) success cannot be told without discussion of the significant contributions made by John McGinnis; however, the story must begin prior to his involvement. In fact, it dates back to the California Rancheria Termination Act of the 1950s and 1960s. Bear River was a terminated and landless tribe, and was not reinstated until 1983, after which they spent years working out of an old building in Eureka, California. Not until 1991 did grant money allow Bear River to relocate to its current location in Loleta, California. One of the early entrants into the market following the passing of IGRA in 1988, the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe (Mille Lacs) opened its first casino in 1991. Joseph Nayquonabe Jr. was a mere 9 years old at the time, but he vividly remembers the feeling of excitement flowing through the tribe.

One of the early entrants into the market following the passing of IGRA in 1988, the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe (Mille Lacs) opened its first casino in 1991. Joseph Nayquonabe Jr. was a mere 9 years old at the time, but he vividly remembers the feeling of excitement flowing through the tribe.