Despite compelling reasons to study the impact of Indian gaming on the health of tribal members, gambling problems among American Indians have received scant attention from the research field. One reason for the dearth of research in this area is the challenge of conducting research with a population that has a long history with research abuses, especially in the area of addictive disorders. How and when should investigators approach American Indian communities? Which research questions should receive priority? To answer these questions, Tribal Government Gaming magazine invited Katherine Spilde and Eileen Luna-Firebaugh to offer guidance to gambling researchers interested in studying American Indian populations.

Both of our institutions, San Diego State University and the University of Arizona, encourage and support academic research on issues related to American Indian tribal governments. Whether legal or policy studies, cultural analysis or public health research, part of our mandate is to strengthen and contribute to the foundations of original research about the important changes taking place in Indian Country. However, many projects that might seem important or interesting from an academic perspective are not meaningful to or feasible in tribal communities, where priorities and beliefs about what is to be shared vary widely from place to place.

To understand why tribal governments are sometimes reluctant to allow “outside” researchers to study their communities, consider the following story: In 2004, the Havasupai Tribe filed a lawsuit against Arizona State University charging that ASU researchers had misused blood samples taken from tribal members who had been told that the sample material would be used for a study on the genetics of diabetes. The Havasupai community members later learned that the samples were also used for research on schizophrenia, inbreeding and migration patterns, without the tribe’s consent. This recent case, while shocking, was reminiscent of other past abuses and reinforced Indian Country’s suspicions of research and the assumption that findings could be used to harm and humiliate American Indian people and communities (Santos, 2008; Sahota, 2007).

Researchers interested in studying the economic and social impact of gambling on American Indian communities must understand the history this story reflects and illustrates as well as the new research regulations some tribal governments have adopted to protect themselves and to exert more control over investigations conducted on or with their communities. We offer the following recommendations to researchers who are thinking about studying gambling impacts or gambling disorders among American Indian communities.

OBSERVE PROPER PROTOCOL

Issues of proper protocol can make or break a research project in Indian Country. As sovereign nations, American Indian tribal governments have the right and responsibility to regulate research on their lands, and some tribal governments have created their own Institutional Review Boards (IRB) for the purpose of evaluating proposals for research on their communities (Sahota, 2007). Investigators should take care to follow the community’s research

regulations when submitting the project to the tribe’s IRB.

We find that academic researchers are often reluctant to approach tribal government officials about potential projects. One simple guideline for dealing with tribal leaders is to consider them as one would any other esteemed elected official or honored representative. Elected tribal chairs and members of tribal councils are the chosen representatives of sovereign peoples and nations. They carry a heavy mantle of responsibility and should be accorded great respect. If the leaders and members believe that the concept of tribal sovereignty is understood and honored by researchers, they will be more cooperative and forthcoming and more likely to contribute their ideas and support to research among their community members.

STRIVE FOR CULTURAL COMPETENCE

The recommendation to develop a project that is culturally competent might sound like obvious advice to those interested in working with native communities. However, in our experience, academic researchers often fail to do their homework or invest time in trying to understand the community’s perspective on important issues. Learn as much as you can about the history, culture, traditions and circumstances of the community you would like to study. For example, try to understand the pace and rhythm of life in the community, which may not always proceed in accordance with your project’s timetable or deadlines. Ceremonies and rituals often take precedence, even over previously scheduled interviews with outside investigators.

In addition to examining your own personal preconceptions, take a critical look at the existing methodology for cultural bias. For example, current screening instruments for gambling problems have not been validated for use in American Indian populations. You might also consider how the view of gambling among Indian tribes might influence your investigation. Whereas the dominant American culture often seems ambivalent about gambling, despite the large percentage of Americans who gamble, many tribes view their own traditional gambling activities as an important and positive part of their history and culture.

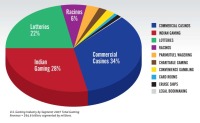

Additionally, for many tribal governments, gaming revenues provide the most significant (or only) source of governmental income, so tribal gaming’s political impacts are understood to outweigh any potential or actual social impacts.

AIM FOR A TRUE PARTNERSHIP

Most importantly, community leaders and tribal members should be involved from the inception of the research project as more than just human subjects to be studied. Researchers should expect—and invite—tribal representatives to monitor your research project and to request continuous consultation and conversation. Be prepared to explain your project again and again to leaders, small groups and individuals and to incorporate feedback along the way. Projects that reflect true collaboration are ultimately the most valuable to tribal communities themselves and may provide additional value to populations of interest to other researchers.

Reciprocity should be the hallmark of research projects with American Indian communities. If investigators make use of the subjects’ time and participation, they should give back to the community by providing resources and skills and by focusing on projects that the community itself is seeking. Hiring tribal members to assist in research activities is a common practice that can benefit the tribe and also make it less likely that research participants will be exploited or exposed to unnecessary risk (Caldwell et al., 2005).

CONCLUSIONS

These are just a few of the many opportunities and challenges involved in the study of gambling’s economic and social impacts on American Indian populations. Despite the many challenges, we are confident that academic researchers who make the effort to conduct community-based, collaborative research in Indian Country will succeed in producing enlightening studies that will benefit both the tribes and the larger gamb

ling field. We support the creation of tribal IRBs to monitor and shape academic research on tribal communities and encourage researchers to learn more about these processes and protocols to ensure successful completion of important work.