Leadership is a nebulous quality. There are many ways to lead: by example, by dictate, by design, by humility, with compassion, using fear or intimidation, and many others.

In Indian Country, leadership carries with it an important mantle. In a community where poverty has been a constant companion; where achievement has often been stifled by educational challenges; and where the best and the brightest are often not recognized, emerging leaders are becoming increasingly important.

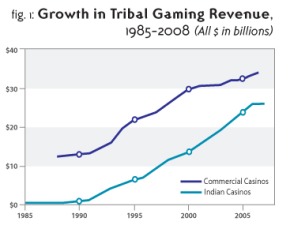

Thankfully, Native America has produced important leaders during the most difficult times for their people. That was true when gaming became an economic generator in Indian Country. Gaming was never a slam-dunk for tribes. It was always a struggle with seemingly insurmountable hurdles thrown up at every turn. Yet the tribal leaders persisted until gaming became a reality and the lives of tribal members improved in many ways.

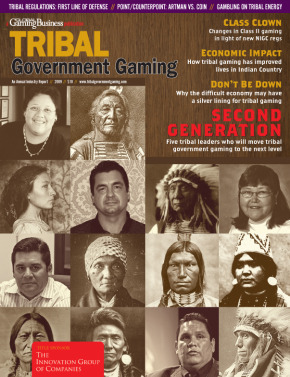

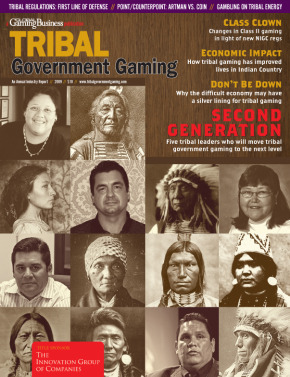

Today, the “second generation” of leaders in the gaming era has to continue the momentum begun by the tribal forefathers. The five leaders we profile here are not only tribal leaders, however. They are leaders in the political arena, the commercial sector and the financial world.

While these five leaders are notable for their achievements and their vision for the future, they represent an entire generation of leaders who will determine the future of their tribes and the future of Indian gaming. So while we celebrate their accomplishments and their ambition, we recognize their time has only just arrived and their mark on Indian Country has only begun to be written.

Each of these leaders employs different strategies and diverse paths in their roles and their relationships with their tribes, but let there be no doubt that their leadership is appreciated and noted.

National Stage

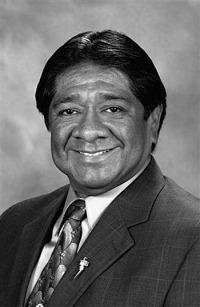

Ernie Stevens, Jr.

Chairman, National Indian Gaming Association

Anyone who has ever heard Ernie Stevens, a member of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, speak-and there have been many in the eight years he has served as chairman of the National Indian Gaming Association-knows that he reveres tribal elders and the “pathbreakers” who blazed the trail for Indian Country, both in and out of gaming.

Even though he himself was honored with a “Pathbreakers” award at a special conference examining the 20 yeas of IGRA at Fort McDowell in Arizona last year, Stevens deflected the honor to speak about people he considered to be especially worthy of the award.

He started with his father, Ernie Stevens, Sr. The elder Stevens was a political activist for Native American causes and for a time worked at the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C.

Stevens speaks reverently of the man who undoubtedly bestowed upon him his passion for Native causes, and who has inspired him to speak so clearly and unambiguously when discussing Indian gaming at the federal level.

And then he moves on to his 98-year-old mother who survived the boarding school era and still speaks the language.

He then recognized another award-winning recipient that night at Fort McDowell, his immediate predecessor at NIGA and fellow Onieda member, Rick Hill.

“He was my counselor at the Boys Club back in the day,” laughs Stevens. “I would not be who I am today without his input.”

Stevens quotes leaders like Wendell Chino and Roger Jourdain, who stood strong against any intrusion into tribal sovereignty.

And it is who he is today that brings out the leadership quality in Stevens.

“These are the people who motivate us,” he says. “Our strong legal position and the power and heart of Indian people are what keep us going through everything.”

With increasing threats of federal oversight, a new administration in Washington, D.C., and, most importantly, the economic crisis, Stevens says the members of NIGA must make adjustments.

“We must take steps to maintain our strong employment base, keep our markets healthy and most importantly, find economic opportunities for those tribes that have little and no chance to capitalize on gaming.

“There’s too much work to do in Indian Country to rest on our laurels and simply reflect on the victories of the past. We must move forward in order to honor those who brought us to this point.”

With the Obama administration in office, Stevens hopes that many of the previous contentious issues that tribes endured with the federal government will not be so controversial.

With the recent Supreme Court decision challenging definitions of off-reservation lands, the administration and Congress will be challenged to pass legislation that addresses that issue.

And the recent move by the NIGC to not adopt changes to the Class II formulas is something of a victory. But Stevens refuses to call it such, and says that he will continue to oppose NIGC regulations that he believes tread on tribal sovereignty, including the agency’s assertion it has the right and duty to regulate Class III gaming.

“We’ve proved in court they were wrong, but that’s old news now,” he says. “Let’s move forward and protect this industry. We shouldn’t have a federal government telling us what’s best for us. That’s over.”

Stevens says another thrust in Indian Country has to be government-to-government relations, even beyond the federal level.

“Working on economic development with the surrounding communities and other tribes is probably the most important thing we can do for Indian Country,” he says.

Stevens may reflect on being the “second generation” in Indian gaming leadership but he’s already preparing for the third.

“My son just got elected to tribal council,” he says, “like me and my father before me. It’s just meant to be.”

The Commercial Spirit

Tracy Stanhoff

President and Creative Director, AD PRO

For some leaders, the call comes from the past and from far afield. Tracy Stanhoff, a successful businesswoman who lived a long distance from the Kansas reservation, says she could not stay away when many tribal members asked her to take over the leadership of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation after the previous tribal chairman resigned.

“My grandparents were removed from the reservation during the Depression,” she explains, “and placed on the Navajo reservation, as many other Natives were. My parents then went to Los Angeles during the encouraged relocation of the 1950s. So I considered it important to answer that call.”

It was in southern California that Stanhoff developed her business, AD PRO, a full-service advertising and graphic design company. She put that business in the hands of her staff during her time as chairwoman.

“When I ran for chairman,” she says, “I won with what was then the most votes in the history of the tribe.”

Stanhoff says gaming has been very good for her tribe.

“Before gaming, there were no paved roads on the reservation,” she remembers. “We’re a progressive tribe, a proud people. And I believe we’re the poster child of what’s gone right in Indian gaming in this country. We used to depend on government grants for all our services on the reservation. Now we have a beautiful government building, recreation facilities, a Boys and Girls Club, health-care facilities and more. Our road system has been built up. Our infrastructure has been improved. A lot of our people are able to come back to the reservation and live on the land. There are jobs that allow this to happen.”

Challenges remain, but gaming has led the way.

“We still have a housing shortage, but because of gaming, we’re able to address that,” says Stanhoff. “From low-income housing, senior citizen apartments, temporary housing for those in transition. While we’ve seem some layoffs in the economic downturn, most people are employed or at least more employable than they ever were before because of gaming.”

In addition to the tribe, Stanhoff says the casino has meant much for the non-tribal community, as well.

“I believe we’ve led a renaissance in northeastern Kansas,” she says. “We’ve spurred the multiplier effect in the area of our reservation. Our fire and police departments have reciprocal agreements with the surrounding communities.”

Stanhoff’s short time as chairwoman spanned an important time for the tribe and included the transition from Harrah’s management to tribal management of its casino. She says the desire to operate the casino and keep all the profits was a two-edged sword.

“Harrah’s management did get us up to speed quickly and they taught us a lot about best practices which we adopted,” Stanhoff explains. “On the other hand, they considered all of their systems and methods proprietary so when they left, it was like starting over from scratch: the computer systems, the players club, HR, marketing… they all had to be replaced.”

And the technical aspects of the turnover was also quite demanding.

“While we owned our players list, just getting it separated from the Harrah’s data was a challenge,” she says.

Stanhoff stepped down only 18 months after taking the job, faced with opposition from some tribal members.

“It wasn’t many members, just a few,” she explains. “Even though I am an enrolled member, because I wasn’t from the reservation, there was some problem with that. But this group was just disgruntled and it wouldn’t matter who was in charge, they would oppose them.”

Stanhoff has returned to lead her company to new heights. It’s the “full service” designation that makes her company unique.

“One of the things we’ve done that makes us different from other graphic design companies is that we do vertical integration,” she says. “We do actual production in house and have all the equipment we need to actually produce the physical piece.”

While she has many Native American clients, she says her business serves both large and small companies.

“Our largest clients are major corporations in the United States: Boeing, American Honda, a lot of energy companies on the West Coast.”

As president of the American Indian Chamber of Commerce, Stanhoff hopes to lead other companies by her example.

“I never faced any barriers I could not overcome,” she says.

Preserving the Empire

Bruce “Two Dogs” Boszum

Mohegan Tribal Council Chairman

For a small tribe in southeastern Connecticut to develop what is arguably the most respected gaming company in the U.S. is impressive. But to keep that momentum and continue forward is the charge of Bruce “Two Dogs” Boszum, the chairman of the Mohegan Tribal Council.

Boszum was first elected to the tribal council in 2004, and was appointed to lead the council one year later. Because he respects the traditions of the tribe-he is also a designated “pipe carrier” who presides at all important events-he understands the importance of those who came before.

“We always pay respect to our elders as people who got us to where we are today-Chief Ralph Sturgis and all the members of the council in those days,” he says. “It’s a good feeling to know that they had the mindset to secure things for the future of our tribes. It’s our responsibility now, to preserve what 13 generations have tried so hard to do.”

With seemingly a constantly depressed economy in the Mohegans’ part of the state, Boszum says gaming has been beneficial.

“We were all on our own for all of our history before gaming,” he says. “Once the casino was open, it gave us some tools to pay for our education, our health costs, the welfare of our people. It’s been a funding mechanism for tribal government.”

And the surrounding towns have also benefitted, he explains.

“For the local community-Montville, Uncasville and other locations around us-we contribute 25 percent of our slot revenue to the state of Connecticut,” he says. “While we don’t pay property taxes, we are involved in local events, helping with infrastructure like sidewalks and roads.

“We also spend close to $500 million in goods and services each year in Connecticut alone. We try to keep it in the state. And that creates about 20,000 jobs outside the casino in new businesses that have opened up in Connecticut to service the industry.”

The Mohegan Sun has cooperated with state agencies to bring tourists back to its corner of Connecticut, according to Boszum.

“Tourism had been dying out,” he says. “We worked with the tourism agencies to bring it back to life. We include local attractions like Mystic Seaport in packages we offer to our customers.”

Boszum says that diversification of the tribal economy isn’t as important with the Mohegans as it might be with other tribes because of the expertise they have developed in casino development and management.

“We’ve become the best in the world at what we do,” he says. “Our core values are outstanding. For now, we’re staying in the gaming business. We purchased Pocono Downs in Pennsylvania and opened a world-class casino there. We’ve been contacted by and are working with other tribes to help them manage and develop projects. Our brand is very strong and people look to us to help them.

“For right now, given the state of the economy, we’re very happy with the gaming business.”

Boszum says the tribe is happy working with the state, but it draws the line at giving up any sovereignty. A recent flap in which the state legislature is attempting to implement a smoking ban throughout the state, including the two casinos, has raised his ire.

“For over 400 years in Connecticut, we’ve talked with the government,” he says. “I deal directly with the governor. There’s no committee, just a one-to-one relationship. The state is not going to come on this reservation and tell the tribe what we can and cannot do. Not under my watch.”

He says the issue isn’t smoking, it’s the state trying to impose its will on a sovereign nation.

“The hotel and all public space is non-smoking,” Boszum says. “You have to really hunt to find a place to smoke. About 82 percent of the entire facility is non-smoking, and going up to 85 percent soon. We banned smoking in all of our restaurants before the state of Connecticut made it a law.”

The Mohegan tribe is trying to tough out the recession by maintaining its workforce. So far, it’s working.

“We’ve had some problems, no doubt. But we have not done any layoffs up until now. And we have not touched any education or health benefits. We feel they are too important to cut back. We want to keep everybody working. When we let them know exactly what’s happening, they understand.”

Back to the Beginnings

Laura Spurr

Tribal Council Chairwoman, Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi Indians

While the second generation of tribal gaming leadership usually means a tribe has opened at least one gaming facility, there still are a handful of tribes that are just taking the first step. And they are learning from their predecessors.

Laura Spurr, the tribal council chairwoman of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi Indians in lower Michigan, is looking forward to her tribe’s first casino, the FireKeepers Casino east of Battle Creek, scheduled to open this summer.

“If you look at Indian casinos as a model,” she says, “I think there are some great lessons. Many started with bingo, especially here in Michigan. Most of them made responsible decisions about expansion and are financially solid right now.”

Like many of the original gaming tribes, gaming means a regeneration of the tribal community.

“For us, we did not have a great number of members locally who could work on this,” says Spurr. “Our members had dispersed into the major cities, so we’re trying to re-establish our tribe and bring them back.”

The Huron Band ran into many of the roadblocks encountered by other tribes-federal recognition, tribe-state relations, environmental issues, lawsuits attempting to stop casino development and much more. But it persevered and finally had lined up all the requisite approvals in late 2007.

But then, the economy had started to tank, and the tribe’s dream of opening a casino seemed to have evaporated. But still, Spurr and the council refused to surrender.

“We were working with Merrill Lynch and met with them on a regular basis to move forward,” she says. “In the first quarter of 2008, we finally had a plan. The financing was a difficult process but we did everything we had to do and it was well-received. We have several strict covenants, but we were able to move forward.

“On May 6, 2008, we finalized the funding and on May 7 the construction company got started. We didn’t even have time for a groundbreaking.”

The dream continues to live today, even though the initial years after recognition were difficult.

“When our tribe was recognized in 1995, we received $196,000 from the Bureau of Indian Affairs,” Spurr explains. “While this is much less than other tribes in the same situation have gotten, we were still able to use this money to build the infrastructure for the tribe. We were able to build a community center, a health clinic and 16 houses on the reservation with Housing and Urban Development funds. We completed all this on time and on budget. We have taken advantage of all the opportunities that being a federally recognized tribe affords us.

“We knew we had to have a healthy and thriving government before we got into gaming and that has helped us prepare for the hurdles we have now overcome.”

While it may seem that Michigan is gaming-saturated with 23 casinos, Spurr says the secret to the FireWalkers casino is location.

“If you look at a map, Detroit is more than 100 miles to our east and Four Winds (a casino operated by the Pokagon Band in New Buffalo, Michigan) is more than 100 miles to the west, and to the north, it’s at least 100 miles to the nearest casino. So we have a radius of 100 miles or more of no competition. This includes towns such as Battle Creek, Jackson, Lansing, Kalamazoo, and even Fort Wayne in Indiana. Yes, there are 23 casinos in Michigan, but a very large land mass. So that’s a lot of space. The only place that is really congested is Detroit, where there are three.”

For that reason, Andre Hilliou, the president of the tribe’s management company, Full House Resorts, fears that the casino will be “capacity constrained” soon after opening. Spurr says she’s conservative, so will wait for further expansion.

“We’re starting with just a casino, restaurants and bars,” she says. “There are plenty of hotel rooms located near the casino so I don’t think we’ll have any problem with that. It may come up in the future.”

Asked where she hopes the tribe will be in five years, she says, “Debt free!”

Youth Be Served

Shan Lewis

Vice Chairman, Fort Mohave Indian Tribe

If there was a trifecta in Indian gaming, the Fort Mohave tribe may have hit it.

Its small reservation spans three states-Nevada, Arizona and California-all with some form of tribal government gaming. Shan Lewis, the vice chairman of the tribe, says, despite the paperwork, the tribe has some great opportunities.

“It’s an advantage,” says Lewis. “It’s not new to us working with three states. We have law enforcement issues, water issues, land issues… so we’re accustomed to having to deal with multiple jurisdictions, towns and agencies.”

The first tribal casino, the Avi Casino Resort, was opened in extreme southern Nevada, on the Colorado River, a few miles from Laughlin in the early 1990s.

“We don’t consider ourselves competitive with Laughlin,” says Lewis. “We cater to the local residents in the three states. We’re a favorite spot for the river crowd during the summer and the snowbirds in the winter. That’s our unique market; our niche. It’s two different worlds.

“Most people like the fact that we’re not surrounded by other casinos and we’re out by ourselves. We’ve got a golf course that Laughlin does not have anymore.”

The Fort Mohave agreement with Nevada was much easier than any other tribal gaming compact, suggests Lewis.

“Although I wasn’t around at the time, I believe the establishment of the casino in Nevada was relatively straightforward because Nevada has always had gaming,” he says. “We just needed to register with the Nevada Gaming Commission and follow their rules and regulations and we were permitted to open. The compact with Nevada is tiny compared to the ones with Arizona and California.”

Prior to gaming, Lewis says the Fort Mohave economy was a struggle.

“We were a tribe that depended a lot on agriculture before gaming came along,” he says. “The results of gaming allowed the tribe to improve the services to our members. It provided jobs on the reservation. It allowed us to venture out to bring other things to the reservation, although gaming is still the number-one revenue generator.”

Nonetheless, the tribe has always sought to diversify its economy, according to Lewis.

“We wanted to diversify so we don’t rely on just gaming,” he says. “We have our own power and utilities company, our own water company and gas stations, smoke shops, tire centers, restaurants and other businesses. Gaming has created a lot of opportunities for us and we have to take advantage of them in case gaming becomes less important.”

Even within the gaming sector, Lewis says the tribe understands that gaming is just an amenity.

“Tourism is as important as gaming,” he insists. “This plays a big part in our marketing. Gaming is hardly even mentioned. We have plenty of non-gaming events, as well.”

Lewis is one of the youngest tribal officials in Arizona, in his early 30s, and when he talks about his predecessors, he is somewhat awestruck.

“So much is owed to the past tribal leaders,” he says. “Being fairly new, I hear the stories. The challenges were immense and I can’t even believe they were able to overcome them. The way the tribes came together in Arizona to agree on one thing was a major accomplishment.”

His goal is to improve the lives of the Fort Mohave tribal members.

“We want to continue to build on our economic development to make lives better for our tribal members,” he says. “Money makes the world go around, so in order to provide better services, you need money. We certainly can streamline policies and procedures to provide better service, but money is important.”

And as important as the past leaders are, Lewis can’t help to look to the future.

“My children are tribal members, so anything that I do to improve the tribe, I’m helping my family, as well. My life is so much better because of what tribal elders did for us years ago, and I just want to honor them by providing the same service to the tribe.”