As tribes across the country work to leverage gaming resources into economic diversification projects, the importance of the economic development corporation cannot be overemphasized.

Although there are a variety of creative approaches to structuring economic development, there are common themes behind some of the most successful: persevering through early struggles and setbacks before finding the right balance between tribal oversight and corporate independence, and the right development strategy, one that takes advantage of inherent advantages or opportunities.

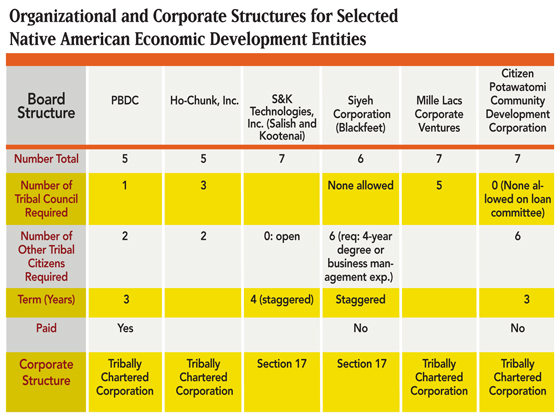

Native American economic development entities are typically governed by a board of directors appointed by the tribal council. Councils approve of overall strategic plans and levels of capitalization and dividend policies. However, day-to-day operations, including personnel matters and investment decisions, are most effective when left to the corporate board and staff. Quarterly reports keep the council informed.

Board member requirements are varied. In some cases, all board members must be tribal council members, while in others tribal council members and officials are not permitted to serve on the board. Frequently, tribes require a mixture of council persons, other tribal members and outside business or economic development professionals.

The two most popular corporate structures are tribally chartered corporations under Section 16, and federally chartered corporations under Section 17. The Section 17 structure has been recommended, due to the perception that it creates a more solid legal base, although that perception appears to be fading, as tribally chartered corporations have been very successful in attracting financing and accessing grants and government contracts. The disadvantage of incorporating as a Section 17 is that it can be a lengthy process to get approval from the Department of the Interior, and it is typically more expensive to establish with respect to legal fees.

If properly structured and strategically developed, Native American economic development entities can successfully overcome challenges—even tribes in remote locations with limited resources and local markets.

TRAILBLAZERS

Mandaree Enterprise Corp.

The Mandaree Enterprise Corp. (MEC) is a tribally owned company, established in 1990 and funded in 1992 with $32,000 from the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikira Nations (MHA) of North Dakota.

4 Bears Casino & Lodge in North Dakota

From 1992 until its “graduation” in 2001, MEC was in the Department of Defense Mentor/Protégé program with Northrop Grumman Corp. Through this program, MEC received technical and engineering assistance and business/personnel management development.

Throughout the next several years, MEC put various multimillion-dollar contracts in place. MEC’s primary business initially was fabricating cables, wire harnesses and printed circuit boards for front-line military weapon systems. In 1998, Mandaree Enterprise diversified into Information Technology Services; clients include the Social Security Administration, Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Agriculture and Data Dimensions Corp.

MEC has also taken what it learned from the mentor-protégé relationship with Northrop Grumman and applied it in its very own, native-focused mentor-protégé program.

Mille Lacs Corporate Ventures

Mille Lacs Corporate Ventures (MLCV) was created by the tribal government of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe, to manage the business affairs of the tribe. It is one of the earliest Native American economic development entities, having been established in the early 1990s as a tribally chartered corporation under Title 16. The corporation’s six-member board of directors is appointed by the band’s chief executive, but ratified by the Band Assembly.

The non-removeable Mille Lacs of Ojibwe has a rich history and culture that dates to a time before Minnesota became a state. Since that time, the language, culture, traditions and beliefs have been proudly and indelibly woven into the fabric of the region. As explained by Joseph Nayquonabe, CEO of MLCV, “Ojibwe people have long influenced and contributed to all aspects of life—art, cuisine, nature, fashion, music, education, spirituality and the economy. These economies developed based on countless generations of learning from each other, and for each other. That continues today with Mille Lacs Corporate Ventures, generating economic stability and opportunity for all people in the region.”

As a company, MLCV has carefully invested time, talent and resources to build a social and economic foundation. It has amassed a portfolio that spans five industries—gaming, hospitality, marketing and technology, in-district investing in and around the reservation, and government contracting.

Some notable businesses within its portfolio are Grand Casino Mille Lacs (above) and Grand Casino Hinckley, two of Minnesota’s premier entertainment destinations; the InterContinental St. Paul Riverfront Hotel; the DoubleTree by Hilton Downtown St. Paul; the DoubleTree by Hilton Minneapolis Park Place; and the Embassy Suites by Hilton Oklahoma City Will Rogers Airport—all managed by Maadaadizi Investments, a wholly owned subsidiary of MLCV. Maadaadizi was formed to provide a full-service investment platform to accelerate economic diversification in acquisition, development and ongoing management.

MLCV’s enterprises help fulfill its mission: to improve the quality of life of Mille Lacs Band members, East Central Minnesota and the communities in which they do business.

Ho-Chunk, Inc. (Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska)

Tribally chartered in 1994, Ho-Chunk, Inc. (HCI) has a clear mandate to separate business decisions from political considerations, as the corporation’s founding document states: “Ho-Chunk, Inc. was established so that tribal business operations would be free from political influence and outside the bureaucratic process of the government.”

HCI’s five-member board of directors currently contains two Tribal Council members and three at-large members. Tribal member Lance Morgan is the original and current chief executive officer. The corporation provides the Tribal Council with an annual report, audited financial statements and an annual development plan. For its part, the Tribal Council appoints board members, formulates the long-term development plan of the corporation and approves annual operating plans. This separation of business from politics frees tribal council members to focus on questions of governance, and enables the business experts at HCI to focus on maximizing the profitability of the corporation.

Initial capitalization (first three years, 1995-97) was provided by casino revenues at a total of $9 million, and HCI was permitted to reinvest 100 percent of its profits for the first five years. As a result, HCI developed a diversified investment and development portfolio of active and passive investments, both on and off the reservation. Initially, HCI targeted opportunities where the economic conditions were the most favorable, which generally meant off-reservation, in metropolitan areas.

Once HCI created a stable income stream from its off-reservation investments, it was able to leverage its existing businesses to create solid on-reservation development. This wasn’t simply a matter of money, but also the development of management expertise. It began its development activities in the franchise business (hotels), so that it could develop managerial talent under the tutelage of an experienced franchiser and eventually move to more sophisticated business activities. This took place as HCI exited some of its hotel investments and focused on its distribution, internet, technology and retail businesses.

S&K Technologies, Inc. (Salish and Kootenai)

Grey Wolf Peak Casino in Montana

The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes have a successful track record with enterprise development, including several profitable businesses.

S&K Technologies, a federally chartered corporation (Section 17) founded in 1999, is a group of 10 companies within three business units, specializing in professional business solutions to government agencies and commercial clients. It was established with a board of directors appointed by tribal council and comprises seven members, with no requirement for council or tribal representation. Staggered terms are for four years.

The strategy for S&K Technologies has been to leverage SBA 8(a) status in the fields of aerospace, avionics, environmental restoration, security and IT. Primary corporate goals are to grow each company, to provide a sustained dividend to the CSKT, and to secure employment opportunities, both on and off the reservation.

The tribes also operate several other successful businesses and have had a long history of economic development, including Eagle Bank, S&K Electronics, Mission Valley Power, a long-running timber operation and S&K Gaming LLC, which operates two tribal casinos.

The proliferation of separate ventures has prompted the tribe to set up an Economic Development Department (in 2008) to coordinate communication and planning between the existing tribal business entities and tribal council, explore new business opportunities and provide due diligence.

Siyeh Corp. (Blackfeet Nation)

Glacier Peaks Casino in Montana

Siyeh Corp. is a federally chartered corporation (Section 17). The six-member board of directors is appointed by a tribal council, although council members are not allowed to serve. Requirement to serve on the board is a four-year degree or business management experience.

When the Blackfeet Nation was organized under the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) in 1935, it was established as both a political entity and business corporation. The nine-member Blackfeet Tribal Business Council manages both the political and the business affairs of the nation.

After decades of failing to establish viable business enterprises—a combination of a remote location, and a lack of business expertise on the part of an essentially political body—the council set up the independent Siyeh Corp. in 1999, to separate business development from tribal politics.

The corporation’s mission is “to generate business, produce revenue, spark job creation and advance economic self-determination.” It operates five enterprises, including the tribe’s Glacier Peaks Casino. It thus far has concentrated on local development, having acquired or developed a cable television company, a local internet provider and a heritage center with cultural products.

Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians (MBCI)

An exception to the trend of separating political from business functions is the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, which began self-directed economic development in the late 1960s, under the leadership of the late Chief Phillip Martin. In this case, it was the vision and business acumen of the tribal chief that drove successful economic diversification for nearly four decades.

MBCI was federally recognized in 1945, but still had unemployment of 80 percent into the late 1960s. Economic development on the MBCI reservation began in 1969, when the tribe set up a construction company to build the low-income homes being funded by a federal program. The strategy was to make a small profit while also teaching skills to tribal members.

Building on this success took many years, but by 1979, the tribe was able to attract Packard Electric to open a non-union automobile parts manufacturing plant on the reservation. This was followed in 1981 by a 120,000-square-foot American Greetings Corp. factory, which was financed by Industrial Revenue Bonds, creating 250 jobs. In 1985, the tribe opened a factory manufacturing automotive speakers in partnership with the Oxford Speaker Company. Three other manufacturing plants opened in the 1980s and 1990s, including another printing company and a plastic molding enterprise.

Over the past 50 years, MBCI has pursued a diversified portfolio of business operations. Today, the tribe operates multiple enterprises that were formed under Tribal Ordinance 56, which created a separate Tribal Business Division, including casinos, hotels, golf courses, commercial laundry, organic farming, a nursing home and real estate management, among others.

MBCI also created a tribally chartered corporation to pursue federal contracting opportunities. This entity currently includes several subsidiaries that are involved in construction, electrical subcontracting and a variety of other service-oriented work, primarily for federal customers. MBCI is ranked among the Top 10 private employers in Mississippi, with 5,000 full time employees.

MORE RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Citizen Potawatomi Community Development Corp. (CPCDC)

Created in 2003, the CPCDC’s mission is to “provide access to capital through loan fund support and business development services.”

Its services include micro-business loans, commercial loans, employee loans, business development assistance and financial education and credit counseling. The program began with an initial capitalization of $1.65 million, which grew to $2.78 million within three years.

Part of CPCDC’s success has to do with its structure, and the separation of tribal politics from loan decisions. CPCDC is governed by a seven-member board of directors: six are tribal citizens, and the seventh is a representative from the First National Bank & Trust.

Loan decisions are made by a four-person Loan Committee, a standing committee of the board of directors consisting of a CPA, a business owner, CPN’s bank and a tribal citizen. Loan committee members are not allowed to hold a tribal leadership position.

Potawatomi Business Development Corp. (PBDC)

Tribally chartered in 2003 by the Forest County Potawatomi (FCP), the PBDC was capitalized in 2004 with $5 million, and received an additional $5 million per year for the next four years. Potawatomi developed a diversified investment and development portfolio of active and passive investments, both on and off the reservation.

The PBDC has a five-member board of directors, comprised of three tribal members and two other tribal citizens. The FCP Tribal Council appoints board members and approves annual operating plans and long-term implementation plans of the corporation. Corporate staff oversees day-to-day management and makes all major strategic decisions.

Transparency, accountability and communication are all key to the success of the PBDC. The PBDC provides the tribal council with an annual report, audited financial statements and an annual strategic development plan. In addition, the PBDC reports at quarterly general council meetings and for tribal newspaper articles and periodic newsletter mailings. A member of the executive council is also invited to attend all monthly PBDC board meetings.

STRATEGIES AND RESOURCES

These examples provide a good representation of the variety of successful approaches to structuring tribal economic development agencies. Mille Lacs is a first-generation model, with the board dominated by council members. Siyeh Corp. and Citizen Potawatomi CDC have chosen to make a clear separation between the board and the tribal council. A balance between council or other tribal members and outside business experts, such as at PBDC and Ho-Chunk, Inc., allows for tribal oversight while fostering a variety of perspectives and expertise.

The case studies of the Mississippi Choctaw and Ho-Chunk, Inc. illustrate two opposing strategies to building economic development. In contrast to HCI’s “outside-in” approach, the Mississippi Choctaw gained its initial experience developing housing and industrial parks on the reservation, eventually expanding off-reservation well after it had established its economic development infrastructure and resources. As the Choctaw experience shows, successful on-reservation development frequently involves asking, “What are we buying and paying for that we could provide for ourselves?” and providing the support needed to locate the resources to take advantage of such opportunities.

Historically, Native Americans have not enjoyed the best possible deals when leveraging their natural resources and assets against federal, state, industrial, agricultural or other commercial activities. The Native-to-Native movement is one opportunity to overcome this disadvantage by dealing directly with other tribes in the buying and selling of products and resources, and to establish native trading and business networks.

There are several organizations established to promote business relationships between tribes and tribal enterprises, including the National Center for American Indian Enterprise Development (sponsor of the annual RES conferences); the Office of Native American Affairs, Small Business Division; the Native American Business Enterprise Center; the National American Contractors Association; the American Indian Business Network; and the American Indian Chambers of Commerce, which operate throughout the country.

Another common tool used by tribal development corporations involves federal contracting through the SBA 8(a) program, designed to help small businesses that are owned and controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals and economically disadvantaged Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian Organizations, helping them compete on an equal basis in the mainstream of American economy. The program strives to promote the viability of such concerns in the marketplace by providing such available contract, financial, technical and management assistance as may be necessary.